ŁA: Professor Grala, you are one of the top European experts on the ancient history of Russia and Muscovy.

HG: Don’t print that [laughs]!

Well, we need some way of presenting you to readers... Let’s talk about a subject that is politically topical. By that, I mean questions about whether the atrocities being committed by the Russian army, the occupation forces in Ukraine, as well as other warfare practices, and finally the justification for the war, are something new in the history of Russia? Or do they have a long tradition stretching back to the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries?

That’s a subject we could talk about for hours...

So perhaps I’ll begin by asking about the ideology that we are observing in the present war. This is characterized on the one hand by a pan-Russian ideology that assumes the national and cultural unity of all Eastern Slavs. On the other hand, we see the security of Russia being called into question, the need to protect the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine, or even the defence of pro-Moscow Orthodox Christianity, the “canonical” form in this interpretation. Meanwhile the legitimacy of the Ukrainian government is challenged because of its “revolutionary” nature. Something new, or tradition?

Well, I’ve tried many times to show the extent to which Russian state ideology is immersed in history and historical rhetoric – how strongly it refers to a selectively treated past. It’s a kind of revolving cabinet with many drawers which are pulled out when needed, each of which contains pre-prepared cheat sheets, flashcards and notes to be used in the current propaganda.

It’s true that the overwhelming majority of slogans, ideas and justifications have been working in Russian state ideology since early modernity. In fact, they’ve been working since the Muscovite state became a pre-modern state in place of the medieval, sovereign Grand Duchy of Moscow, when it became a state with ambitions to absorb, digest and chew up other entities of Rus’.

So let’s start with the pan-Russian ideology.

The problems with the title “Vseja Rusi” and claims to the patrimony of the Rurik dynasty – the so-called the testament of Kalita[1] – and so on have been ubiquitous phenomena in the political doctrine of the Muscovite state since the time of Ivan III.[2] Here we are talking about the “of All Rus'” formulation in this title. Following this, such a formulation of a title is the assertion of concrete territorial claims to diverse parts of Western Rus'. After all, if we’re all masters of “All Rus'”, then we have every right to all its parts. And to avoid any doubt, there’s a further clarification that specific provinces are detailed that are regarded as their own. Since that’s Rurik’s heritage, then of course it’s ours, and that’s especially funny because, remember, for a long time in that conflict – at least until the Jagiellonian dynasty died out – on the other side of the border there were rulers who had a considerable portion of the blood of the Rus' dynasty in their veins, and if the dynastic factor were to play a role here, from the perspective of dynastic law the Jagiellonians[3] have every right to rule the Rus' lands, not only because they inherited them from their ancestors, but simply because they’re Rurikids too.

To weaken this argument, Moscow questions the legitimacy of the Gediminids and Jagiellonians. It bastardizes them. It insinuates that they are the descendants of stable boys who served the Rurikids in Polatsk, impregnated some Ruthenian princess or married the pregnant wife of their deceased liege, and therefore became the heirs to the capitals of Rus' lands. These arguments were still being used in the era of Ivan the Terrible. They stopped using them for very mundane reasons: it suddenly turned out at the time that a large section of the Kremlin elite had Lithuanian-Ruthenian roots. But telling them every day that they were bastards wasn’t a…

Political solution, as they say...

There’s the classic example of Ivan the Terrible beating aristocrat number one, who’s a close cousin of his kniaz Mstislavsky,[4] a Gediminid, screaming “You old Lithuanian dog! Ruthenian meat has grown on your bones”, etc.

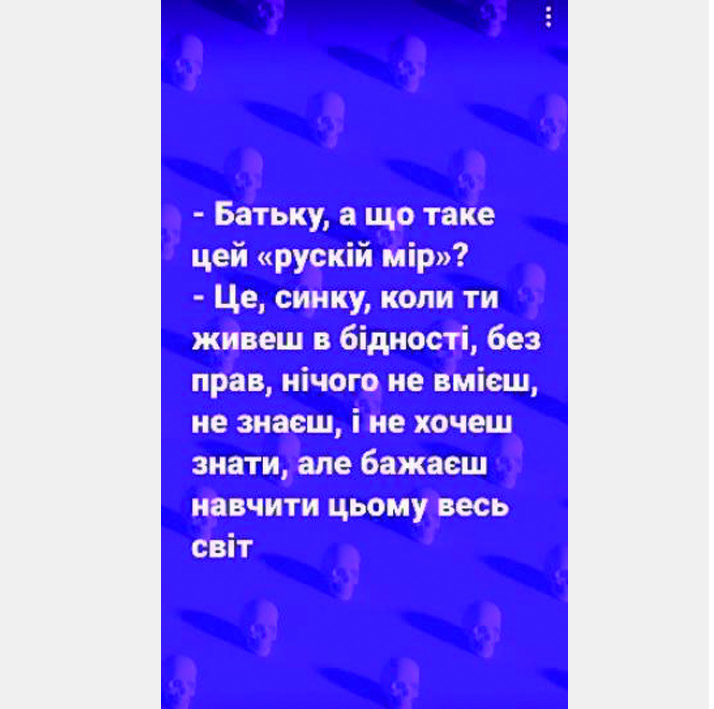

In short, the idea that everything is ours and that there’s one Rus', indivisible and ours, is very reminiscent of that nasty, difficult phrase from Soviet times: “Тam nužen mir, no želatelʹno vesʹ” (we need the peace, but preferably the whole).

That will be untranslatable into English. Because “mir” means both peace and world.

We need both peace and the world, ideally all of it [laughs]. In any case, that approach has been around for a few hundred years. The nineteenth-century ideology, when that was the justification for the partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth – grabbing the lands of today’s Ukraine and Belarus – didn’t come up with anything new. Solovyov, Klyuchevsky and Karamzin[5] actually worked on material prepared by diaks[6] and knizhniks[7] from the second half of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth century. I’d also remind you that the scale of this appetite was also nothing new, because even in those distant times they were working out how to make things that weren’t Russian part of Rus', which must have seemed dubious even to people at the time. So, we take Astrakhan, which had nothing to do with Rus',[8] but we come up with the idea that, phonetically, Astrakhan actually resembles the Tmutarakan[9] of Old Rus' and it’s the same. It’s the same.

If a Rurik is a kind of rotating figure because even enemies of Russia can invoke him, we can point to an ancestor Jagiellonians can’t refer to: the Roman trace, Octavian. Because the rulers of Moscow supposedly directly derive from Octavian’s brother Prus, who never actually existed. Prus and Rus are phonetically similar, but it’s also a prospect, God willing, for Prussia…

Of course…

So Prussia can be tacked on too. And so on and so forth. All these wretched sermons, they’re all stuck onto the historical material in some way.

I take it that the name Muscovy, which right now many in Ukraine propose to restore, was also a response to those claims of the elites of the time of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state and Poland. Correct?

It’s more complicated than that. Firstly, this term appeared in the West at the time when the Muscovite state, the Grand Duchy of Moscow, was indeed a Rus' udel principality[10]. This did not fully overlap with the concept of Rus' – they needed to be separated. But Muscovy is a technical term. Muscovy was the lands surrounding Moscow. Finally, the problems in Western Europe, even among cartographers, regarding the whereabouts of Russia Rubra,[11] Ruthenia,[12] or Ruthenia Alba,[13] etc., are quite large. Remember that the term Ruthenia Alba, i.e., Belarus, was also sometimes used, for example, for Veliky Novgorod. On some cartographical sketches, Halych and Volhynia also suddenly turn out to be Ruthenia Alba, which comes as a complete surprise to us.

The whats, hows and whys are a long and complicated discussion. Certainly, in the West for a very long time the concept of Moscovia was used as a purely technical concept to precisely define this political entity in the concrete boundaries subject to the authority of the person sitting in the Kremlin.

The perspective of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was indeed somewhat different because, for us, when this Muscovite ruler started giving himself titles such as Gosudarʹ Vseja Rusi i velikij knjazʹ moskovskij, the addition of “all Rus'” means that his claims were expanded beyond the borders of his own state. This was dangerous for us, so we responded: “You are not Vseja Rusi, you are Muscovy, Moscovia, that’s it. Because Russia, Ruthenia, is us”.

But was this term “Muscovy” the only one used by the ancestors of today’s Poles or Ukrainians?

No. We have a classic example from political terminology, from Ukraine, that contradicts that. I mean Khmelnytsky’s speech to the Cossack elites in Pereyaslavl, when he very clearly distinguished the tsar of Russia – he distinguished Russia from Rus' (Ruthenia). That’s the most interesting thing. Look, a few times in this fierce speech he said the Russian tsar, the Ruthenian nation. Intellectuals from the Mohyla circle,[14] the Kyiv circle, also made this distinction. So it’s not the case that it was always only the concept of Muscovy that was used. What’s important is something else. None of them – the Poles, Rusyns and Lithuanians – would use the concept of Rus' for Muscovy, that is Russia. And that’s the key. Rus' is us.

I see, and in that case, what about the other element that is so present in propaganda now, the undermining of the Ukrainian government’s legitimacy to hold power, given that it arrived there as a result of a coup, gosudarstvennyj perevorot, Majdan. Were arguments challenging the legitimacy to rule also even used with the elective kings, who actually didn’t have as many rights as the hereditary tsars of Russia?

Of course it was. At a certain point, the Jagiellonians were regarded as bastards. Meanwhile, the competitors in the Baltic zone, the Swedish Vasas, were even seen as people not worthy of rivalry because they were the “descendants of swineherds and pork traders”, to quote a letter from Ivan the Terrible to John Vasa,[15] the Swedish king and father of Sigismund.[16] We can go further: Stephen Báthory, an elective king, is presented as a Saracen layabout, a Turkish minion, who could not be compared to the natural monarch that the Muscovite ruler was.

The rule of all elective kings is seen as incomplete because it is elected. A very common theme in the correspondence with Vilnius and Krakow in the sixteenth century was the assertion that the king was not a true natural ruler because he depended on his magnates. As he was elected, he wasn’t an absolute ruler, except it wasn’t really about the elective nature, but something else.

What was that? The system of government?

Now, in Putin’s system, this phenomenon is known by the resonant name “vertikal vlasti”[17], yet in the Russian version this “column of power” resembles a hydraulic press. There’s a ruler, he presses a lever, and that’s it. This can be illustrated magnificently by the mentality of the Russian elites even at the beginning of the seventeenth century – I mean the famous discussion between the boyar Golovin and our Maskiewicz,[18] the cavalry captain in Moscow. Golovin, who had a brother in Poland and read Polish books, a liberal and enlightened magnate, said to the Polish nobleman: “For you, your freedom is pleasant; for us, our bondage”. And this wasn’t about any characteristics of a slavish soul, as they see here, but about a different understanding of the mechanism of monarchy and state.

So, I assume that the Muscovites and the inhabitants of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth had a different view of what the state is. A different ontology.

Either there are authorities and democratic regulators, as we have, or – as in Tsarist autocracy – the only source and guarantor of all laws is the monarch. Everybody serves the monarch. They are all raby, whether boyar or peasant. And so this bondage is in fact freedom because it made us equal before the majesty of the ruler. This is tortuous reasoning, of course, but this is a continuum visible from the sixteenth century until today.

This was also why the origins of the Polish kings were questioned. In fact, as long as possible, tsarist candidates were also proposed as being better for the throne of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth because they were justified by the right of blood. Incidentally, that would rebound in an amusing way after the line of the Muscovite Rurikids died out in the late sixteenth century, when the Vasas began explaining that they were actually an offshoot of the dynasty, together with the Rurikids (as descendants of the Jagiellons, so of the Rurikids on the distaff side), and now the throne was rightfully theirs. But that’s another story entirely.

In that case, could we say that, for example, Catherine the Great’s propaganda against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which pointed out that there’d been revolution there and that the Constitution of 3 May[19] was a toppling of the social order under the influence of dangerous French ideas – that all this propaganda that we know from the late eighteenth century was not purely instrumental? Was it partly simply an actual reflection of the beliefs of the elites of the time that the kind of Republican order they had in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was something abnormal, and dangerous for Russia?

Certainly. As an aside, again this is reflected in the present day. I remember a discussion on this subject in Russian media, in the press – a discussion on the legitimacy of quelling insurrections and the Third Partition from 1795. Speaking in defence of the torn-up Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was the late Valeriya Novodvorskaya,[20] who took a terrible beating as she was told that in fact Europe, and especially the Holy See, should be grateful to Russia, and Catherine in particular, for preventing the transfer of godless Jacobin ideas[21] and atheist nihilism to Eastern Europe, which thus became a bastion of fundamental Christian values. They also noted that Moscow deserved credit previously because it alone had recognized the dissolution of the Jesuit order. And, of course, the Jesuits were the elite of the Church.

This exaggeration of the radicalism and revolutionary nature of the postulates of the constitution and the uprising[22] is extremely characteristic. That all started a little earlier, of course, at the time of the Targowica Confederation,[23] because already then there were slogans presenting the constitution as threatening the social order. But after Targowica and the Second Partition – when a huge socio-political revival began among the elites, especially among Crown Poles, and there was a plethora of Jacobin clubs, etc. – of course those Jacobins had about as much in common with French Jacobinism as a pruning knife with a guillotine. Remember the caricature depicting Polish Jacobins preparing for revolution and kissing the royal hand? In the times when the skulls of Dantonists and then Robespierrians were falling, this picture did not, of course, suggest far-reaching political radicalism, yet still this Jacobin bogeyman played a colossal role. In fact, I think it was also used quite skilfully in Polish circles because it weakened the national unity.

We know that then, for instance, relations between Russia and Prussia could be so tense that Catherine and the Prussian king threatened each other with who would release Kościuszko from jail, and who would release Madaliński, right?[24] But they had one thing in common: preventing revolution, because at any moment the Prussians would join the struggle in revolutionary France, and Russia would guarantee that no democratic unrest would break out here. So, of course, that motif had an effect, sure. It would also have an effect later, during the November Uprising.[25] The representatives of the Russian authorities would tell the conservative section of the French public that the Polish insurgents were transgressors – foreigners disrupting the existing, fixed and time-honoured European order, just as they would try to persuade the Holy See that in fact a curse should be put on the rebels because they had broken a vow. What else was Mickiewicz’s dispute with the pope about, if not that?

I take it that these words of Mickiewicz’s – “Ah, French and Germans! Just you you’re your turn!/ Soon tsarist ukases your ears will burn;/When on your napes you feel the scourge’s blow/And behold your cities in the lurid glow […] Then, I reckon, you’ll be at a loss for words”[26] – are to some degree a reflection of the polemic?

That is disillusionment, great disillusionment, because in Mickiewicz’s Ordon’s Redoubt[27] we have “when a Parisian messenger licks your feet?”, right? This poem also addressed the tsar: “Warsaw alone defies your power, raises a hand to you and pulls off your crown”. But there’s more of this in Polish literature, this disillusionment, because as I say about Horace Sébastiani,[28] our combatant who camped in the same tent as Polish generals, etc., and he accepted that – told the French that “there is order in Warsaw”… What were the words? “Oh Frenchmen! Are our wounds of no value for you? At Marengo, Wagram, Jena, Dresden, Leipzig, and Waterloo. The world betrayed you, but we stood firm. In death or victory, we stand by you! Oh brothers, we gave blood for you. Today you give us nothing but tears.”[29]

I must admit I wasn’t familiar with that verse of La Varsovienne.

As an aside, that last sentence fits perfectly with what was going on a year ago when Western governments were discussing what the scale of aid for Ukraine should be, those German helmets, first-aid kits and so on – I remember how a moved Prof. Jan Kieniewicz[30] plucked out that very quotation in one university body.

I’ll go back a little to earlier times. From the sixteenth century, public opinion in Western Europe was affected by very critical reports about the reality in the Muscovite state. I think Sigismund von Herberstein was the author of the first such work, which then entered the canon of those seen as unfavourable to Russia. Information also certainly got through about Ivan the Terrible’s oprichnina,[31] the Massacre of Novgorod.[32] In 1654, the Massacre of Mstsislaw[33] took place, and a year later the Sacking of Vilnius.[34] And then, in the eighteenth century, the Massacre of Praga took place – an atrocity that even today for the Polish national memory is more or less the same as the Bucha Massacre is becoming for Ukrainians.

How did the Russian, Muscovite state react to the information about these acts of barbarity? Was there any sense of a need to explain themselves, or not?

I’d just like to go back briefly to your previous questions and make it clear that – alongside the factor of dreamed-up ethnic unity and liberation of the supposed Rus' confraternity from Polish oppression – the problem of the Orthodox religion was also very much stressed. It was advanced as an aspect of saving the true faith with a certain civilisational dimension. Remember that for two centuries this allowed the Russian state to harness an ideology that had actually been vanishing in Europe since the end of the Middle Ages, apart from the Turkish front perhaps – that of the Crusades. Ivan the Terrible marched to Polotsk, to Ruthenian lands, to one of the capitals of Rus' Orthodoxy, accompanied by clergy and blessed by the hierarchs.[35] He went to rescue Christian temples from the hands of “heathen Lutherans and deceitful Latinists”. He attacked Livonia, which of course was never actually Russian, invoking on the one hand the imagined legacy of Yaroslav the Wise, meaning a source in a Rus' chronicle from 1030 about the construction of a fortress in the territory of the invaded Chuds.[36] On 30 September 2022, Vladimir Putin did the same thing when he publicly cited the legacy in Livonia.[37]

Of Alexander Nevsky?

Earlier. He cited the Primary Chronicle (Tale of Bygone Years). So, Yuryev, not Dorpat, not Tartu,[38] just the Old Russian fort of Yuryev. Full stop. And the same thing would be cited by Alexei Mikhailovich while marching on Vilnius and also aiming for Warsaw and Krakow. When the tsar set off for the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth after accepting the tribute of the Zaporizhian Cossacks,[39] Patriarch Nikon[40] blessed the banners because they belonged to Crusaders! They were going to liberate the Orthodox Christians, fight for their rights, and if the Orthodox Christians didn’t want this, that was another matter. Clearly they hadn’t come round yet, but when we did liberate them, they would realize how lucky they’d been.

These slogans were still alive in the eighteenth century. After all, the First Partition was presented in the context of defence of dissidents’ interests and rights. It was at this point that the tsar, or in fact the tsarina, became an advocate of the Orthodox ranks of subjects of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the supposedly oppressed Orthodox Christians, but also Protestants, whose Christianity had previously been questioned. Finally, this denominational moment was again used by Russia, this time Bolshevik, in the 1920s. At home, we shoot bishops, again we’re delegalizing the patriarchy, etc., but we do not accept the autocephaly of the Polish Church[41] because the Orthodox Church in Poland is to be subordinated to the Moscow Patriarchy and that’s that. It’s an identical mechanism.

Returning to your second question: there were indeed many atrocities, but I’d divide the early modern era into two periods.

Which?

Up to the mid-sixteenth century and before. The fifteenth century and the first half of the sixteenth is a period when Muscovy was still exotic, little known, and only being recognized. This was also the reason for Herberstein’s[42] compendium – after all, he wasn’t particularly spiteful in his explanations but just wrote what he saw. Most importantly, while in the late sixteenth century Muscovy read that and gnashed its teeth and said they were ancient fairy tales, we thought it was practically an anti-Muscovite pasquil, and that was why Báthory sent it as a present to Ivan the Terrible. But when it was produced, it was received almost as an ethnographic interview, a description of customs in Moscovia. The contented Vasili III hung the famous sable fur on Sigismund von Herberstein, who he had himself portrayed in gravure for his work. So, he was rewarded for the description. His Muscovite interlocutors were not at all surprised.

But then everything started to change. Paradoxically, we changed too, because that’s a good indicator. We sent Herberstein's book to Ivan the Terrible as a record, a catalogue of certain insults and accusations. However, Herberstein had previously been accused in Poland of being a Muscovite jurgieltnik,[43] and when he was riding in Krakow he had a brick thrown at him from a roof. So everything went awry. Why? Muscovy ceased to be as exotic as it had been under Vasili III or Ivan III. There were Dutchmen, the English company,[44] increasingly frequent emissaries, a growing range of diplomatic contacts – you went to Muscovy and Muscovy went too. In addition, it’s worth remembering that a large number of Muscovite fugitives were enlightening European opinion. But it started from the Latskys,[45] and only then did the generation of the Kurbskys[46] describe those strange things. Descriptions also started to appear from those who served the tsars or were forced to. We have Staden,[47] but above all Schlichting,[48] who was an excellent source because being the translator of the tsar’s physician for so many years meant being in the Kremlin and seeing everything from inside. Actually, he saw too much and scurried away at the first opportunity. We have the first mercenaries in the Muscovite service, who also then brought news. Admittedly, at first, service as a mercenary was quite awkward because it was a “one-way ticket”, because they’d go and sign up for service without realizing that it was damn hard to return, but some managed to, including the famous Taube and Cruse.[49] Cruse even served in the oprichnina and served overseeing Muscovy’s clients in Livonia, for example Magnus of Denmark.[50] But then they resisted in Vilnius, so they began to trot out pasquils on Muscovy, of course. Before that they offered – and this was an important moment – their pens to the Muscovite tsars, offered to write for Europe how things really were, that is an apologia for Muscovy and a pasquil against the Jagiellonians, our state.

So people had to come to Muscovy from the West to convince the Muscovite elite that lots of bad things were being written about them in the world. Muscovy didn’t read that before, and there were two reasons for this. Firstly, not many people were able to read it. And if somebody was able, he often did not risk informing the tsar because, of course, it’s easier to torture the messenger than his paymaster.

They also didn’t realize the power of the printed word. I once wrote about the phenomenon of Orsha propaganda: that Konstanty Ostrogski’s victory over Chelyadnin’s army at Orsha,[51] apart from stabilizing the front and preventing further Muscovite annexations in Ruthenia after the fall of Smolensk, had one more dimension – propaganda purposes. The Jagiellonian court made excellent use of the printed word in the form of countless ephemeral prints, occasional literature, theatre shows, publications in your Romes, Lübecks, Viennas and Venices. And, finally, even a kind of touring circus, exhibiting living witnesses of the triumph, meaning Muscovite prisoners, who, transported there in their natural costumes, were as exotic as arrivals from distant Africa.

That was all a huge propaganda victory. Muscovy couldn’t oppose it with anything in the European diplomatic market and was able to limit the effects of defeat domestically by adapting various reports in Rus' chronicles, etc. But it had no response to confrontation with Jagiellonian propaganda. But even that is insignificant compared to what happened when Ivan the Terrible attacked Livonia, because an attack on Livonia was an attack on the German world – not just some Poles and Ruthenians and Lithuanians. It was an attack on the German world, on the Hanseatic cities. This marked the beginning of gigantic production of pamphlets in the German language showing the cruelties and crimes of the Russian army. Those stories of maidens blowing up fortresses so as not to fall into the hands of Muscovite rapists. Gravures showing women hung from trees by their hair, with Muscovite-Tatars shooting arrows at them. All this shocked public opinion. It was discussed by the Imperial Diet.

The Livonian Confederation didn’t withstand the Muscovite attack, ultimately accepting the Jagiellonians’ protection and becoming a fiefdom of Sigismund Augustus. That reduced the Holy Roman Empire’s interest, but the initial reaction was very aggressive towards Russia.

In that case, when did Muscovy start to realize the importance of propaganda?

At this point, because it was also associated with one more phenomenon. There was increasing knowledge of foreign languages in Muscovy, and the posolskij prikaz[52] gained a new function: preparing government bulletins. Actually, extracts of what was being written around the world were prepared for the purposes of the tsar and his advisers. These started to be shown, in fact later, in the seventeenth century, and this would be an enormous change that is crucial for our discussion, when the so-called Vesti-Kuranty began in Moscow, when the ambassadorial office began to collect newspapers and ephemera from Europe and immediately translate them for the use of the tsar and his closest advisors. The Muscovite elite also changed because they began to know languages. In the second half of the seventeenth century, when we say proudly that the unexploited Polonisation of Muscovy took place, it wasn’t just about Polonisation. Polonisation is part of Occidentalisation, which is largely related to the seizure of Ukrainian lands, including Kyiv, i.e., an educational centre of a magnitude that did not exist in Russia, and to the cadres that were subsequently deported from there.

As for material culture, customs, costumes, art, etc., we forget about the “trophies” taken like in 1944 or 1945. After all, in the war with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth,[53] the lands of Crown Ruthenia and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were pillaged enormously. Łukasz, you know Moscow well, you’ve walked around there and your Russian friends have shown you the pride of seventeenth-century Muscovite art, the Krutitsky Court, the fired tiles and so on. But where do they come from? That’s not Russian, Muscovite art. These are craftsmen taken away with their entire workshops from Mstsislaw, Vitebsk, Orsha, etc. We’ll talk about the massacre, the Mstsislaw Massacre. Who was spared? Qualified craftsmen. They were taken away. We speak of how they began to look at European art. Yes, they did. They even brought exhibits over for themselves. Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich ordered that as many as five cupolas be taken down from the Radvilas Palace in Vilnius after it was captured[54] because there were no such cupolas in the whole of Russia, while the columns were ripped out with ropes from the porticoes, loaded onto carts and transported to Moscow, because there was not a single ancient Renaissance portico in Moscow. That was not cultural transfer, but material transfer, which only began to play its culture-forming role through imitation.

OK, so I’ll play the devil’s advocate. In Western Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, terrible things were being done too. Sweden even today, contrary to the resolutions of the peace treaty from 1660,[55] still holds some of the Polish cultural goods plundered during the Deluge.

That’s true, but there’s an important turning point. Still, the terrible stories about sixteenth-century atrocities must have resonated less than those of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, because Europe wasn’t all sweetness and light either. The Massacre of Novogorod, which was known about in Europe, wasn’t qualitatively different from either the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre or the Sack of Antwerp, was it? But for Europe a certain important turning point was undoubtedly the Thirty Years’ War, which was still cruel. Just think of the massacre and sacking of Magdeburg.[56] Still cruel, but culminating in the Peace of Westphalia, which essentially also legally regulated the nature of warfare – the nature of conflicts in Europe. And, suddenly, it turned out that although wars were going on in Europe, we no longer had reports of such mass atrocities and crimes. That was over. Indeed, it ended there. There were individual cases that were spoken and written about and punished. In Eastern Europe it went on a little longer – for instance, the Cossack wars were rife with atrocities on both sides. The Battles of Batoh,[57] Stavishche,[58] and Polonne,[59] etc., but that was different. The norm hadn’t yet been established.

It also seems that a civil war has a different status than international conflicts. A civil war, unfortunately, by definition permits greater atrocities because it stays in the family. So, for example, the Massacre of Uman[60] had some resonance in Europe, but just a distant echo because in fact it wasn’t clear who, how, with whom and what for. Whereas, almost at the same time, the Siege of Izmail by Suvorov [61] – without any special efforts of Turkish diplomacy, which was also highly advanced in terms of the art of printing and use of publications, almost like the Muscovite diplomacy – still resonated widely.

We also need to remember one more thing: for a very long time Russia couldn’t take part in the circulation of information because it didn’t have printing. And even when those Vesti- Kuranty[62] were made, when they made 20 copies by hand for the tsar and boyars that were later multiplied somewhere in a corner. But that’s a completely different object of information to hundreds and thousands of papers, isn’t it? The press market didn’t exist because there was no press. Besides which, how could there be a press market and prints when there wasn’t a single printer? For a very long time. The Sacco di Vilna[63] was something, a paroxysm of these… Muscovite atrocities, which, by the way, even today the Russians won’t admit to, just as they won’t admit to the Mstsislaw Massacre, which must have been awful. Since the survivors soon came to be known as the “unscythed” (nedoseki in Russian), which is what those who had survived the Mstsislaw Massacre were called in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. News of it was terrible. Everyone heard about it, and today we have absolutely phenomenal reactions from Russian historians. Not long ago, our mutual acquaintance wrote that it was a natural reaction of an army to a fortress not wanting to surrender. I’d just point out that this modus operandi had previously been used very effectively, but by Genghis Khan.

Undoubtedly.

Really. But really, after the Thirty Years’ War, fortresses in the Netherlands and the Rhineland also fell that didn’t want to surrender, and yet no one slaughtered the entire civilian population.

Of course, that’s also a sign of a certain delayed civilisational development.

In Russia now a certain characteristic two-stage line of defence is used. First, nothing like that took place. And second, it was justified by the nature of the time. And both reasons might be given in one breath, although…

They logically cancel each other out.

And here, as an aside, we could also venture another assertion. European opinion in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was quite happy to use the instrument of spreading guilt. Particularly the eastern contingents were blamed – the Tatars, Bashkirs, Cossacks, Circassians. Pointing the finger – “it was them”. I think that the current pontifex would like that very much because Pope Francis also diversified in that way, expressing his astonishment at the idea that it could be the Russians.

This approach would suggest that the Vilnius and Mstsislaw massacres gathered some colonial contingents, but this was done by Trubetskoy’s all-Russian army, with the so-called mercenary regiments of the new outfit and so on. The second observation is very sad for Russia: from the mid-seventeenth century onwards, I don’t know a single case of European commanders and monarchs participating in military atrocities against a civilian population. But in Russia it was a different story. Let me remind you of the murder of four Basilian clerics in Polotsk[64] by Peter the Great, accompanied by his staff officers and his favourite, Menshikov – a holy place for Rus', the ancient Cathedral of Holy Wisdom in Polotsk. This demonstrated a whole array of soldiers’ vices. The “Christian monarch” demanded access to the tabernacle and to the relics of Jozafat Kuncewicz.[65] When he was denied, when the Basilian superior refused, apparently he cut his ears off and certainly murdered him. The door to the tabernacle was torn off. The tsar personally trampled on the host. He wanted to profane the relics, and the resistant Basilians were drowned in the river. As for the prior, one story is that the tsar personally ran him through with a sword, assisted by Menshikov. This was a crime perpetrated by the supreme commander of an army – and an ally at that, an allied army. Peter I was in Polotsk as an ally of the Polish king, the great Lithuanian duke Augustus II the Strong.[66] That’s a shocking crime, isn’t it?

The arguments used by the Russians concerning various later events, especially the Massacre of Praga, are also telling. Firstly, the murdered burghers, including women and children, were victims of the storming. Secondly, Suvorov personally endeavoured to subdue it and saved them. Thirdly, everything is exaggerated. Warsaw was actually grateful for being saved, because after the massacre the municipality of Warsaw supposedly handed a snuffbox with an inscription to its saviour, namely Suvorov. And generally the fact is that – as it says on Russian Wikipedia, for instance – under the influence of Polish historians, this highly biased interpretation of Suvorov's action in Warsaw during the storming of Polish capital gained popularity in French and English literature. Well, I’m not sure if, for example, Baron Engelgart,[67] a cousin of the tsar’s family and officer of Suvorov’s army, who described the atrocity, was a Polish historian. I’m not sure if the hero and guerrilla leader in the Napoleonic Wars, Denis Davydov,[68] who wrote about it, was a Polish historian. Certainly, the English ambassador, Gardiner,[69] who described what he saw with disgust, was not a Polish historian. I don’t know what influence the memory of Jewish kahals in the Polish lands, preserved for centuries, might have had on English historians. In the museum in Zamość, you can see an illuminated manuscript showing the participation of Jews in the defence of Praga, and the Massacre of Praga perpetrated by the Muscovites.

But Suvorov did not deny committing the massacre?

No, he didn’t. His conduct during the storming consisted of running with two turkeys along the rampart and shouting, “At least let these two poor birds survive the slaughter”, and at the same time, after blowing up bridges so the people couldn’t flee, enabling illegal crossing, to be shared by… The Russian command gained material benefits; this is confirmed in sources. This was, if I remember correctly, told to Denisov by the hero of the Caucasian Wars, Yermolov. There’s an awful lot of evidence, and it makes no sense to pretend it didn’t happen. But the most tortuous argument is that it was a massacre which was a response and revenge for the slaughter of the Russian garrison during the Warsaw Insurrection.[70]

So let’s consider how legitimate this was. Firstly, shortly beforehand there had been a massacre of survivors on the battlefield at Maciejowice,[71] bayoneting the wounded with cries of “For Warsaw!” So how many times can you get vengeance? Secondly, there was no massacre of a Russian garrison, which in the Russian narrative, incidentally, came from who knows where. It wasn’t an Intourist excursion, after all, but an occupation corps (around 12,000 soldiers, not including Cossacks). Why was the building on Miodowa Street, the Russian embassy, turned into a fortress? It was more like revenge for the ignominious retreat of the Russian army, where a mob armed with sticks and axes defeated the Polish garrison of Warsaw, despite being outnumbered three to one. The Russian garrison was made up of battle-seasoned soldiers, Suvorov and Kakhovsky’s[72] soldiers remembering the victory over Turkey. That was a terrible disgrace. Even the Prussians, who endeavoured to meet them and allow the incursion through the Krasiński Garden, described how extremely inept the Russian actions had been and that they had in fact simply retreated in a stampede, leaving up to 4,000 dead and 1,500 to 2,000 prisoners. And then there’s one more classic issue that I really like to pester my Russian interlocutors with. What happened? Sleeping garrisons were slaughtered? How did the Warsaw Insurrection begin? With the ringing of all the bells for the Easter service. Compare what time bells ring in Catholic Warsaw, and what time according to the rules of service in a garrison should soldiers be washed, shaved and at arms? In fact, at 5 a.m. the Russian army attacked the Arsenal (the operation had been planned earlier to nip any revolt in the bud) – presumably not while asleep, and that was the signal for a popular uprising against the Muscovites.

They were drunk…

Or, lastly, something from the Massacre of Praga, when they say that Suvorov’s order to destroy the bridges was not because he wanted to slaughter everybody. Just taking into account the state of the army – drunk on blood but also liquor – he was afraid that they might be hit by a counterattack of the still quite numerous Polish forces from the other bank of the Vistula. Because, as Davydov relates, the jaegers were so drunk that, for example, grenadiers from the Phanagoria regiment were unable to clean their weapons and hired soldiers from other regiments to do it. I know that’s a rather awful, terrible story, but it’s true. The sources are unequivocal.

Let’s remember that, in the shadow of the Massacre of Praga, in our national “roll call” of tragedies and wartime atrocities there is also the famous massacre in Ashmyany in the Vilnius region, now in Belarus. From the November Uprising, when in April 1831 Colonel Vershalin’s corps slaughtered the town’s population for fraternizing with the insurgents, also not sparing churches, slaughtering the population that took refuge there, murdering the clergy and desecrating the shrine. That resonated quite widely in Europe. But this revived notions especially among the Germans and French about these savage Russian atrocities, as in Suvorov’s time. It’s interesting that this was what resurrected a certain idea that had died out during the Napoleonic Warsaw. Because you have to hand it to Alexander I that he so much wanted to be the arbiter of Europe and its angel of peace that the fact is that, for example, his entry to Paris was conducted not only in exemplary fashion, but with iron discipline. There were no excesses. There were a few in the provinces, especially by the Cossack detachments, but the existing studies show that they were relatively sparing, which incidentally can be explained by the nature of the political manoeuvres. We are bringing peace. We are returning the French throne to our ally. We are in an allied country.

These experiences of the November Uprising, and then also the January Uprising, were very much shaken up by Alexander’s actions. The wars going on in the Caucasus at the same time were not so significant. Essentially, although the English observed that conflict and there were Polish volunteers there, essentially it was seen as just a colonial conflict. The Russian state was bringing order to savage peoples within its frontiers, and Russia’s colonial rhetoric was completely understandable and acceptable to colonial French or English rhetoric.

It was a slightly different case with Russia’s later operations in the Balkans. But there again, entering the Balkans in an effort to construct this “Russkij mir” in the Balkans in the war for the liberation of Bulgaria, there was an attempt to demonstrate leniency and goodwill to civilians as a Christian Slavic population. Interestingly, after the Napoleonic Wars the role of the European bogeyman was assumed by Turkey with the Chios Massacre[73] and the pacification of Greece. But then came the November Uprising, and Russia returned to the place of satrap and brute, which was why when the Crimean War came, we in Europe were now fighting against bloodthirsty beasts, weren’t we?[74] There was pacification, but then also the January Uprising and so on.

I’d like to touch upon what I think is another important subject – the question of whether Russia understood treaties in the same way as Western European countries or the culture of Latin Europe. Was there a conviction that a treaty should be signed in good faith?

I think that when signing treaties, Russia was usually operating in the way shown in a cult scene from the film Our Folks: a court is all well and good, but justice must be on our side.[75] Again, I’ll point to the complete divergence in the early modern era of Russian norms and European norms, late medieval norms and early modern norms. Both the articulated reasons for the war and justification of claims varied widely. There was a key moment in the Polish–Muscovite negotiations during the Deluge, in the negotiations at Nemėžis (Niemieża).[76] On the one hand, the Muscovite boyars, all those Trubetskoys[77] and Odoyevskys[78] accompanied by diaks, the whole time were operating within the old Muscovite narrative. Territorialism, the sacrosanct, inalienable rights of the whole of Rus' but also the tsar could break the previous perpetual peace[79] because he had acted to defend his name against all your untruths, because by printing various texts in your countries you insulted him and wrote contemptuously about him. He gave you a chance, sent a delegation to you with a list of culprits to be executed, their hands cut off, books burnt, forbidden! And what did you do? The criminals who offended the tsar still walk God’s Earth. You thought we’d be fooled when you publicly burned a couple of pages torn out of books.[80] But the books can still be bought. You’re dishonest, and that’s why God punished you. On the other hand, there was a delegation made up of diplomats trained in negotiations with Western partners, unfortunately mostly Crown Poles, and they didn’t understand anything about what Muscovy was.

The Lithuanians did better.

Yes, they did. And the Crown Poles, not a clue, although Warszewicki[81] wrote a work in which – after his experiences from the negotiations in Yam-Zapolski – he explained explicitly that the position in Muscovy required a great deal of resilience because Muscovy was stubborn, repeating the same lines over and over, obdurate and incapable of negotiating. He described them very pointedly. But our diplomats didn’t take advantage of that afterwards, probably because they weren’t professional. They didn’t make use of the amassed experience, and the people who travelled were often not well versed in negotiations with Muscovy.

So the Poles went to Niemieża armed with what? With legal literature and moral arguments. Moral arguments only amused the Muscovite clerics. After all, our tsar won, right? He captured everything. That means that Providence was on our side. Long live the “Imperija”! And it doesn’t matter if… So what if we broke the treaty? But fate proved that we were right, because we beat you, and not you us.

That sounds familiar.

No, in fact it’s decisive. No legal concerns. The funny thing there was that the arbiters in those negotiations were supposed to be Habsburg mediators – as foolish as ours. They had no clue about it all. They went there and made a big effort, convinced that they were important diplomats, but they were swiftly called to order. And what did they hear in Moscow? If you don’t like it, there’s the door. They also wrote these reports saying that something strange was going on. There was no dialogue.

During the Deluge, we were helped by the fact that we had one asset that Muscovy had never had in its hands: an expectative to the throne after the childless John Casmir. And this somewhat evasive offer that the tsarevich or tsar might become the future Polish king meant that again Muscovy was taken in. We had some experience in this because we fooled Ivan the Terrible at one point too. I mean the Lithuanians did because the Crown Poles didn’t have much of a clue and thought it was treason and that the Lithuanians were conducting private negotiations.

Going back to the starting point, we can see there, in the mid-seventeenth century, a clash of two ways of negotiating – two completely disparate diplomatic methodologies. Up to then, the Muscovite diplomacy had operated exactly as it did in the time of Ivan IV, Vasili III, etc. The wide entry, meaning the gains from the Truce of Andrusovo,[82] but also the involvement of the Ottoman Porte in the war in Ukraine in the 1660s, would attract Europe’s attention to Muscovy as a potential participant in the Holy League and would very much increase contacts with the European world. And here, in fact, Muscovy would have different instruments because it would have the intellectuals from the Kyiv circle and limitless translators. After all, the first Russo-Chinese treaty has a Latin variant.

What’s extremely interesting about all this is the fact that the Kyiv-Mohyla circle, but also the Belarusian one, played a role in creating that intellectual base. The Golitsyns[83] started speaking Polish, and Artamon Matveyev[84] started speaking Polish and learned Latin. The head of Muscovite diplomacy in Alexei Mikhailovich’s time, Ordin-Nashchokin,[85] wrote letters in Polish to Polish magnates and knew Latin. Everything changes, everything changes. Basically, everything Peter I would later agree to, even encourage, and apply to the Russian elite – that is travelling to study, which had previously been forbidden or very much limited – would become absolutely self-evident. Because from now on they’d be prepared differently. While the negotiations conducted in Alexei Mikhailovich’s time would take place po starinie, the diplomacy of Peter the Reformer – not yet Peter from the time of Karlowitz – was becoming European diplomacy, adopting European instruments and using European literature and European legal norms, when that suited, of course.

So should we take it that Russian diplomacy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was now European?

I’d say rather that the European instruments were an added value because, when necessary, they dusted off the old norms and convictions. This attitude to the European arsenal is easiest to express with the concept of a consumer attitude to Western innovations. Consumer, utilitarian. Peter understood that, and then his successors did, especially Catherine and Alexander. It was an effort to raise an audience abroad. An effort to create milieus that would act in the interests of the Russian raison d’état and the Russian narrative and reproduce Russian propaganda. And indeed, that’s a fantastic qualitative leap. From propaganda that was unwritten, calculated for the domestic market, and inept when confronted with such inventions of humankind as printing, to propaganda that hires pens, buys authorities, buys works justifying its aggression. And drip, drip, drip.

So that was how Catherine became the Semiramis of the North, was it?

Ah! Catherine is… fascinating! Where did so much talent come from in this provincial representative, raised in the Stettin garrison, of what was after all a flagging German dynasty? Gigantic determination, enormous talents, but presumably this Western background, that was… Note that this was the first Russian monarch who saw the West from within and had grown up there. She was well read; she saw how propaganda worked, knew what popular literature was, knew how to create. Yet the growth of popular literature, even literature, even fiction in political service during the War of the Bavarian Succession, during the Seven Years’ War, was enormous. She knew that and endeavoured to bring that to Saint Petersburg. Hence her literary efforts, because there was a group of court writers. It was very poor literature, but it was there. She endeavoured to give it a European lightness and reflection. She wrote some historical plays because history was becoming a state weapon. Literature served the state. And this gave rise to all those dramas about Rurikids and so on, staged in the court theatre, written under a pseudonym, accidentally public and so on and so forth. Literary polemics. We form the mirage of an enlightened court. We teach men of letters how important it is in the state interest to use art, i.e., literature, historical topics – we reach wholesale for art.

Previously in Russia, political manifestos had been expressed through votive buildings because the connection between religion and the state was strong. Votive buildings and cults of saints. And then Peter engaged in the state cult of Alexander Nevsky and construction of the Saint Alexander Nevsky Lavra, etc. With Catherine it was completely different – secular buildings, secular festivities. Her advisers and magnates followed her example. We always pride ourselves here in the fact that the first Russian anthem was a polonaise written by a soldier, a traveller, Kozłowski,[86] etc. We completely forget that it was a work originally commissioned by Potemkin[87] for a feast in honour of Suvorov – as it happens, right after a war crime, the slaughter of Izmail.

So one more question. In the history of 13 wars between Poland and Russia, I don’t think Poland ever violated a peace treaty – if anything, in one case, it violated a truce. In other words, Russia was the aggressor. How was the breaking of treaties justified? Was it considered important? Were treaties generally signed in good faith, or was it reckoned that their validity depended on how long abiding by them would be beneficial for Russia? Was there even a common understanding of the words “law” or “treaty”?

The concept of law essentially only appeared at the end of the seventeenth century. Law was not a norm but a certain catalogue of natural laws including, for example, Russia’s rights to the entire area of Rus'. But the concept of law as a certain system of values didn’t exist. Moreover, there was also a peculiar understanding of the obligations that result from signing a treaty. For example, I’d point out that, more than once, Muscovy was terribly concerned when a monarch of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth died and a truce was in force. They then hastily dispatched a delegation to extend the truce. Of course, it didn’t require extension because it had been signed, but Muscovy had a different understanding – pacts die together with the signatories.

That’s a lack of understanding of the state’s legal personality. Rather a concept of the state as the property of the monarch.

The state at this point was not a legal entity and not a guarantor of fulfilment of a treaty – the guarantor was the monarch. Muscovy was measuring its legal and systemic norm against our reality, so it didn’t quite understand what the big deal was. And that’s quite important, because indeed another question is that of implementing treaty resolutions. There were always problems with that. For example, when there were obligations – the regularity of border congresses and delimitations enshrined in the truces, up to the Treaty of Polyanovka, the biggest attempt at pacification of relations between Muscovy and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth – they never worked out.

There were also problems with ratification, as you remember very well, actually even with ratification of such fundamental acts as the Treaty of Perpetual Peace. Supposedly Sobieski vowed perpetual peace on the Market Square in Lviv, recognizing Grzymułtowski’s treaty,[88] but in fact the General Sejm didn’t ratify it. And, until the partitions, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in colloquial terms, played dumb, and the treaty both existed and didn’t exist.

Muscovy agreed to that?

For Muscovy, if the monarch had sworn an oath, it was ratified. Again, the clash of two worlds. The king was everything, the Sejm nothing.

But do I remember rightly that when the Sejm finally ratified Grzymułtowski’s treaty at the beginning of Stanisław August’s reign, it didn’t ratify the cession of Kyiv to Muscovy?

Yes, yes. That was also… A lot of different strange things were going on there because it was a question of titles. A question of monarchical titles. But the titles remained from before Andrusovo.

The Polish king didn’t renounce his titles, those of Duke of Chernihiv, Severia, Smolensk, etc. Moreover, remember that there was a hierarchy in place the whole time for the lost lands. Of land offices and senators’ offices in the Sejm of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in the Senate. The lands were gone, but the offices existed, well, in partibus infedelium. In the terminology of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, those areas were called “avulses”: lost lands which, God willing, it would be possible to recover. They were not lost forever.

So these acts simply looked different on the two sides of the border. Poles under-interpreted them, and Muscovy overinterpreted, right? But the real politics was in its hands, not ours, and that strikes me as an interesting topic.

Since Moscow invested in propaganda in the eighteenth century, it used the services of “influencers”. We know that Voltaire served Catherine, that he was commissioned to extol her rule.

Not just him. There were attempts to contact Diderot, for example. But the funniest thing is that, after all, the work which backfired terribly in Moscow, or rather Russia, namely Astolph de Custine’s account,[89] was originally intended as an apologia. After all, the French writer received an invitation and safe conduct because he was supposed to write how things really were – good, that is. He was supposed to show foolish Europe how marvellous Russia was: ruled by an enlightened monarch, enlightened absolutism and so on and so forth. But unfortunately, he came, he saw and he wrote. They cured him there and then. I have the sense that this otherwise intelligent guy had no idea what a terrible blow he was aiming at his hosts when writing this book because he just described it as he saw it without thinking about the whole interpretation. When they began reading it in the West, they reached slightly broader conclusions than he did, especially as it was him that stuffed himself on caviar, drank champagne, nibbled on beluga and walked around in Russian sables, and they had to read that codswallop.

And I’d say that this technique of the Russian authorities remains unchanged. After all, what did things look like in Soviet Russia? What was the aim of those famous delegations of Polish writers,[90] inviting your Wańkowiczes,[91] Słonimskis,[92] etc.? They were meant to write good things; they were shown everything that could be shown, except the reality as it really was. Screeching. And then there’s Bertrand Russell,[93] right? There’s Arnold Toynbee’s[94] marvellous expedition. When I first read that description, I cried with laughter because that was exactly what the adventures of my generation on Soviet rail looked like.

How do Russians now react to the critics of bygone Russia?

We’ve talked about Suvorov and the Massacre of Praga. So, the whitewashing of Suvorov is still going on. Once… Zvezda, the channel of the Russian army, made a series of educational, journalistic films about Suvorov, and they did an interview with me asking me to show what Suvorov looked like from a Polish perspective. They hadn’t heard much about the Massacre of Praga, but I committed a worse abomination because I said that, regardless of that peaceful Suvorov who saved Warsaw, there were greater abuses and greater distortions in his legend. They were very surprised. They asked which ones, and I said, for example, your Russian myth that this was a commander who was almost the only one in human history to never lose a battle. And that’s not true. Not only did he lose, he got an absolute thrashing from the Bar Confederates at Tyniec,[95] literally on the eve of his victory over them at Lanckorona.[96] The recording at my house was quite long, 45 minutes of material. Then they didn’t release a single second. Suvorov is simply sacred. He’s inviolably sacred, despite being a sociopath, butcher, and in fact a primitive man, with the biggest, quite monumental proof of that being the edition of his correspondence published by the Academy of Science.[97] In my opinion, the editors didn’t read that correspondence, because if they had…

They wouldn’t have published it?

They would have censored it.

Suvorov was without doubt a very talented commander: a typical commander of the Russian school; a commander as a spiritual father like your Zhukovs, just a “lobovyj udar”, no manoeuvres, just “bayonet charge”, bleeding the opponent and yourself and so on. He was perhaps the fullest manifestation of that. The later ones… all those Paskeviches,[98] etc., were much cleverer. After that there was one operating in a similar way, albeit not on the same scale, who would also become the idol of the Russian public…

Who?

Mikhail Skobelev,[99] who, if he’d been allowed to go on storming Pleven[100] as he wanted to, then the Turks would probably have had their Bakhmut. But an old German, the defender of Sevastopol, Count Totleben,[101] came along and said it was unacceptable and that he’d capture Pleven with a method of small means and small costs. Because, he said, “General, we came to storm the fortress and not to allow you to cavort on a white horse at the cost of soldiers’ lives.” And he captured it. Meanwhile, Skobelev became a hero.

The next idol is Zhukov, a commander who eclipsed Rokossovsky. And yet people wept that they had to serve under Zhukov and everyone tried to follow Rokossovsky, because then they had a chance of survival. I was told this in an open text by the son of Rokossovsky’s and Zhukov’s translator, who entered Rokossovsky’s command from 1941.

So this was the creation of some kind of expert myths, even though in the West Zhukov is known as the conqueror of Berlin, the model of an eminent Soviet commander, even though after all we have the generally available recording of his talks with the great commanders of the Allied armies: his talks with Eisenhower about the mortality of soldiers, etc., which caused consternation among Western commanders.

What mattered was success. The support of the Russian state, promotion of certain figures.

I think one important topic has been missing from our conversation: the divergence that took place between Europe and Russia. Europe, which from the Thirty Years’ War onwards began to standardize all laws, the laws of war, prisoners’ rights and so on. Russia has been very selective in its history about abiding by that and respecting it. It also comes down to two different traditions of warfare. Indeed, far be it from me to use the clichéd, calqued question of Mongol heritage and so on, but I would point out that a good number of the wars waged by Russia over the centuries were wars waged in the East according to Eastern rules, and they were wars waged by Eastern contingents. Heaven forbid, I’m not saying that the Russians didn’t slaughter and pillage, because they did, but they had an excellent model, an excellent justification. And it’s absolutely obvious that this was the norm. That was how they fought in Khiva, in Bukhara, in Samarkand. And so what? Then they brought those experiences here. We all remember the terrible experience described – long questioned by the Russians – in the book Berlin 45. A million rapes, etc. Do you remember Melchior Wańkowicz’s book On the Trail of the Smętek?[102]

Yes, very well.

You remember one short description. There’s a description of a village of Old Believers. There’s also a short description of the arrival of the Russian army in East Prussia.

I didn’t notice that. Was it Wojnowo?[103]

Yes, because it went unnoticed, but the description is characteristic. Those columns of soldiers, shouting, “solovej, solovej, ptašički”. And drunk. And those… running, bloody, in a woman’s torn clothes. The pre-war censors didn’t guess what it was about… Very odd. They let it through. And the Polish communist censors didn’t react? They didn’t notice. Or they decided it was the tsarist army.

Right.

Imperialist wars. But it’s one to one. Savages invading Eastern Prussia, like in the film Rose, right?

Of course.

That’s it exactly, mass rapes, etc. When my Russian colleagues tell me that these are Western inventions, I say, “Hang on…”. And Prussian Nights by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn,[104] who described that? And the cries from behind the wall, right? I’m a Polish woman, I’m a Polish woman.

My own aunts survived it… These aunts survived in Ostróda at the station only because the railwaymen burnt the staircase and there was no entry to the second floor. Polish railwaymen on German railways.

My grandmother, who lived in Sępólno Krajeńskie at the end of the Second World War… that was in Poland then but a dozen or so kilometres from the pre-war German border, smeared tar on herself and would tell us that her sisters did the same to look worse.

But what’s the most important thing here? That we’re talking about acceptance and encouragement. Because there’s the rhetoric about defeating the beast in its lair, that this is Prussia, the cradle of Nazism, etc. At the same time there’s encouragement to take revenge. And it doesn’t matter that much of that population isn’t German. So, where’s Stalin’s statement that the Red Army man marches on, beats the Germans and liberates us, and you’re taking pity on the women, you wouldn’t even let him have them.

As an aside, as they said, looting, looting as an instrument of war. How surprised we are at this terrible looting in Ukraine. Tearing out toilets and so on. We experienced all that here in ’45. And Vilnius experienced it from Alexei Mikhailovich.

So in 1655 it was the same as in 1945?

They took stoves away because they didn’t know what that kind of European stove looked like, for example. They took away the sewage framework, because they took everything. Remember that technologically… In Moscow at the time, it was actually technologically impossible to cover a roof with sheet metal. So they rolled and ripped off the roof sheathing. That was all there. And then the looting of cultural goods. Starting from the start, there wouldn’t have been the first Russian library, there would be no public library without the Załuski Library.[105]

Looting in enemy territory, trophies of war. All understandable. Besides which, saving cultural goods, as my Russian colleagues explain. And then bang, we have a description of the Bashkirs and Cossacks having the duty of loading the books into trunks, but they didn’t fit, so they cut them with sabres. Those disgusting Frenchmen. That Napoleon stole so much, you know? And they took it all off to Paris. I wonder how the Italian medieval city archives arrived in Saint Petersburg, for example, from Cremona, an ally. They plundered whatever they could.

And they still haven’t returned it. In that case, this is an excellent contribution to the discussion on the continuation of Russian methods of warfare.

A continuation, not a straight line. Because we have something like a sine wave. There are some periods when Russia tries, for propaganda or ideological reasons, to resemble the rest of the world. Sure, the Seven Years’ War: we went into Königsberg and behaved decently, admittedly because Königsberg was to be annexed, but we went into Berlin. We behaved calmly there too. The contributions just add up terribly. But then we have the excesses of the Polish and Turkish wars of Catherine’s era. Next come the Napoleonic Wars. Alexander took great care of his army’s good name, demonstrating a veritably Roman clementia, accepting surrender and so on and so forth. That makes an impression. The Kingdom of Poland is at stake, Alexander is to be the future monarch, an idol. And word goes around that this is a civilized army now. And then bang! The Massacre of Ashmyany. The Pacification of Lithuania. And the image of Russians as Barbarians.

This sine wave depends on two things: how the Russians behave and to what extent the ruling milieus in the West are interested in publicizing or hushing up what’s really happening there. After all, it’s not as if the world didn’t know what was happening in Germany under the Russians. But, firstly, we know how the Allies behaved in the Rhineland, and they behaved badly. And especially we know, and every intelligent person in Europe knew, how the Allies behaved in Italy.

And the final topic everyone is very sensitive to: the murder of prisoners on the battlefield. If you went to the museum of the Battle of Friedland[106] in the Kaliningrad Oblast, the favourite theme for showing the crimes of the West is that in the Battle of Friedland during the storming, French soldiers bayoneted a Russian general who was being carried off the battlefield by his soldiers. That indeed happened. But when I was shown that I just asked how the indignation related to the killing of prisoners at Maciejowice. Or to cutting off prisoners’ right hands after the Massacre of Praga? Come on, gents, you can’t have it both ways.

It would even be humorous were it not tragic that in the Russian narrative they try to whitewash and justify everything. In the same way, wars of aggression are traditionally presented as rescuing the object of the invasion. And I don’t even mean Ukraine, but Poland earlier. You know what was the most wonderful idea of Putin’s propaganda, almost simultaneously with the annexation of Crimea?

What?

Minister Medinsky came up with “pre-Katyn”, associated with the Napoleonic era, a supposed crime of Polish soldiers near Gzhatsk.[107] A monument was built, a sign put up.

There’s also something that defies any attempts at logical analysis: the famous trip to France of activists of the military history society and the French funding of memorials on the battlefields of Napoleon and the coalition in 1814. Remember that Russian nomenclature even now talks about a war of liberation of Europe from the Napoleonic regime, and at best it’s called the “zapadnyj pochod Russkoj Armii” – they came up with the idea of putting monuments up for the poor French.

To the gratitude of the French nation.

Yes, yes! And the French were supposed to chip in for the monument in Fère-Champenoise, where Russian cavalrymen slaughtered three squares of the French National Guard. They thought to themselves that they’d put up monuments of gratitude for liberating France from Napoleon. That’s genuine – Russian Military Historical Society delegations travelled to France specifically for that purpose...

It only goes to show the Russian elites’ enormous problems with understanding Europe and knowledge of Western Europe.

Today’s elite uses history and historical narrative as a flail, hammer or piledriver and sees it as an operational game, a tactical manoeuvre, just like operational games of espionage. They don’t treat it as a process governed by rules stemming from certain norms.

And if the facts contradict that, then too bad for the facts.

No, they’ve gone up a level. If the facts contradict it, they don’t exist. Facts are annihilated.

I think that we could actually finish on that note.

It’s a brutal punchline, unfortunately, but a true one.

Many, many thanks for a fascinating discussion!

Interview was conducted by Łukasz Adamski

[1] Ivan I Kalita (1288–1340): ruler from the Rurikid dynasty, son of Daniel, the first prince of Moscow, from 1325 Muscovite prince, from 1328 Grand Prince of Moscow. In 1328, he also received approval from the Mongol khan Ozbeg to collect taxes for the Golden Horde from the entire territory of Rus', thus receiving the appellation Kalita – pouch.

[2] Ivan III, or Ivan the Great (1440–1505): in 1462–1505 Grand Prince of Moscow. In 1480, he commanded the Muscovite army during the Great Stand on the Ugra River, conventionally seen as the end of the 250-year Mongol yoke. In 1492–1494 and 1500–1503, he attacked the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, resulting in Muscovy’s conquest of much of the so-called Lithuanian Rus' (including the Chernihiv and Severia lands and part of the Smolensk region). He introduced the two-headed eagle as the official coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

[3] The Polish branch of the Gediminid dynasty, which ruled in Lithuania; derived from the Grand Duke of Lithuania, Jogaila, who also became Władysław II Jagiełło, King of Poland. Dynastic connections meant that the Jagiellonians were frequently and closely related to the Rurikids (Jogaila himself was the son of Uliana, Princess of Twer).

[4] Ivan Fëdorovič Mstislavskij: son of a cousin of Ivan IV the Terrible, one of the main leaders of the Muscovite army during the Muscovite–Lithuanian War in 1558–1570, as well as a senior court official in the Kremlin during the rule of Ivan the Terrible.

[5] Sergej Solov'ёv (1820–1879), Vasilij Kliučevskij (1841–1911), Nikolay Karamzin (1766–1826): Russian historians, each of whom wrote a fundamental work on the past of the Russian state.

[6] Clerical official in the Muscovite and Russian state.

[7] Intellectual in medieval Muscovite Ruś – the early Russian state.

[8] A former territory of the Golden Horde, from 1459 an independent state (khanate), conquered by Ivan the Terrible in 1556.

[9] Capital of one of the sovereign Rus' principalities, extant in 965–1094 (?) in what is now Crimea, previously part of the Kazar Khaganate.

[10] “Udel” principalities were states that were independent from the supreme authority of the Grand Duke of Kyiv in the Middle Ages – the early Modern era. States of this type were created under the conditions of the patrimonial monarchy as a result of feudal fragmentation.

[11] Also Ruthenia Rubra, Red Rus': historical region in the borderland of modern-day Poland, Ukraine and Belarus.

[12] The Latin name for Rus'.

[13] The Latin name for White Rus' (the eastern part of today’s Belarus).

[14] Group of intellectuals from the Kyiv-Mohyla School (Academy), established in 1658 on the basis of the Mohyla College, founded in 1632 by Petro Mohyla, the Orthodox metropolitan of Kyiv (1596–1647).

[15] John III Vasa (1537–1592): King of Sweden in 1569–1592. In 1572–1583, fought with Russia for control over Livonia.

[16] Sigismund III Vasa (1566–1632): King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1587–1632, King of Sweden in 1592–1599.

[17] Vertikal' vlasti, the vertical of power (Rus.) is a political term that means the hierarchical subordination of the executive authorities to each other. It is used as a cliché in modern Russian propaganda as a symbol of positive autocracy and order, allegedly characteristic of Russian reality as an integral feature of Russian political culture.

[18] Vicepalatinus of Novgorod Samuel Maskiewicz (1580–1632) befriended the Muscovite boyar Fyodor Golovin (Fëdor Golovin) (?–1625) during a stay of the Polish garrison in Moscow (1610–1612). Upon returning from Russia, Maskiewicz wrote a diary featuring stories from the events of 1594–1621, including his discussions with his brother-in-arms, Golovin.

[19] Government law from 3 May: Poland’s first constitution, passed by the Sejm on 3 May 1791. In 1792, Russia declared war on the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth on the basis of the supposedly illegal nature of the constitution and persecutions of Orthodox Christians. Defeat in the war resulted in the Second Partition of Poland (1793).

[20] Valeriya Novodvorskaya (1950–2014): a Russian dissident.

[21] In this context, revolutionary liberal ideas and propaganda encouraging a coup d’état.

[22] The insurrection of 1794 against Russia and Prussia, responsible in 1793 for the Second Partition of Poland. Named the Kościuszko Uprising after its leader, Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746–1817).

[23] The Targowica Confederation: a confederation of opponents of the Constitution of 3 May, organized in 1792 and supported by Russia. In Poland it became synonymous with treason.

[24] Antoni Józef Madaliński (1739–1804): one of the Polish leaders in the Kościuszko Uprising.

[25] November Uprising: war between Congress Poland, the small Polish state established at the Congress of Vienna in a union with the Russian Empire, and Russia in 1830–1831.

[26] A translation from Adam Mickiewicz's poem “Forefather's eve”.

[27] Ordon’s Redoubt: a poem of the Polish bard Adam Mickiewicz from 1832 on the storming of Warsaw by the Russian army during the November Uprising.

[28] Horace François Bastien Sébastiani (1772–1851): a Napoleonic general, participant in the expedition to Moscow, French minister of foreign affairs in 1830–1832.

[29] Extract from La Varsovienne (Warszawianka), a patriotic song from 1831. The lyrics were written by the French poet Jean-François Casimir Delavigne (1793–1843), influenced by the November Uprising.

[30] Jan Oskar Kieniewicz (born 1938): a Polish historian.

[31] Term for Ivan the Terrible’s terror in 1565–1572 against the boyars. The word comes from the Old Russian oprich, meaning “separately” (the organizational basis for the machine of terror was a distinct unit of the state).

[32] The Massacre of Novgorod in 1570: Ivan the Terrible planned the murder of the inhabitants of this merchant city, which the tsar suspected of disloyalty. At least several thousand, and perhaps more than ten thousand, people were killed.

[33] A massacre in Mstsislaw, a town on the eastern fringes of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, committed on 22 July 1654 by the Russian army under the command of Kniaz Aleksey Trubetskoy (1600–1680). Over ten thousand townspeople were killed.

[34] The burning of the Lithuanian capital by the Muscovite army in August 1655, combined with pillaging the city and murdering its inhabitants.

[35] Ivan’s Polotsk Campaign during the war with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1577–1582) for rule over Livonia.

[36] In the Russian Primary Chronicle, Livonia was described as a land of Ruś.

[37] Speech by Putin at a meeting with young businesspeople and scholars marking the 350th anniversary of the birth of Peter the Great (9 June 2022): http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/68606.

[38] Yuryev, Jur'jev: Slavic name for Tartu from the Primary Chronicle; Dorpat was the German name.

[39] A reference to the events of 1654, when the Zaporizhian Cossacks along with the lands they controlled accepted the protection of the tsar. This resulted in the outbreak of war between Muscovy and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

[40] Nikon (1605–1681): Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus' in 1652–1666.

[41] The Russian Orthodox Church did not recognize the autocephaly of the Orthodox Church in Poland, which it received from the Patriarch of Constantinople in 1924.

[42] Siegmund (Sigismund) von Herberstein (1486–1566): an Austrian diplomat. Herberstein twice stayed in Muscovy, in 1517 and 1526, and in 1549 he wrote Rerum moscoviticarum commentarii, in which he described the history of Muscovite Rus' from ancient times until the rule of Vasili III, the Grand Prince of Moscow in 1505–1533. Herberstein gave information about the country’s religion, politics, economy and customs.

[43] An Old Polish term for corrupt officials and politicians who took a wage from foreign states.

[44] The Moscow trading companies in the sixteenth century; the main trading partners at the time were Holland and England.

[45] Ivan Latsky (?–after 1552): a Muscovite boyar and diplomat. In 1534 he crossed to the Lithuanian side, leaving notes about life in Muscovite Rus' and cartographical commentaries.

[46] Andrej Kurbskij (1528–1583): Russian aristocrat from the Rurikid dynasty, commander of the Russian army during the rule of Ivan the Terrible, essayist and religious writer. In 1564, he defected to Lithuania. In correspondence from 1564–1579, he polemicized with the tsar on political and religious topics, and in his works he described Russia’s history and customs.

[47] Heinrich von Staden (1542–1579): German burgher, adventurer, supposed oprichnik of Ivan the Terrible, author of several reports on the Russians and Russia itself, where he lived in 1564–1576.

[48] Albert Schlichting (?–?): German from Pomerania, the author of two pamphlets about Russia written in the mid-sixteenth century. Schlichting was taken into Russian bondage in 1564 and later served as a translator and servant of the tsar’s doctor in 1568–1570. In 1570, he fled to Lithuania, where he wrote accounts of his stay in Moscow.