Previous scientific research has already studied neighbourly relations[1] between Jewish and non-Jewish residents of various countries in various eras.[2] Many articles in Holocaust research have shown that returnees very often faced a number of difficulties in the countries to which they returned after the horrors of the Second World War. Such works have addressed the “second-lives” of objects that were appropriated by non-Jews after the Shoah,[3] regardless of whether their owners returned. Of course, several studies have also focused on returnees or their reception.[4]

This study aims to briefly introduce the history of the Jews of Szeged, give an overview of certain aspects of antisemitic sentiments in the region, and describe the relations between Jews and non-Jewish society during and after the Second World War. Moreover, it examines survivors’ relationships with their non-Jewish neighbours, including narratives of the reactions of the local non-Jewish population to Jewish returnees; it also describes accounts of attempts to get back confiscated property and depicts life immediately after the war in Szeged.

The viewpoint for the research for this study was primarily historical, supplemented with an overview of the Jewish history of Szeged. The documents of the Szeged Jewish Community Archive (SzJCA), including letters and requests from survivors, served as the primary source for this contribution. To complement this source material, along with testimonies from interviews conducted by the USC Shoah Foundation and the National Committee for Attending Deportees (DEGOB), local newspaper articles from 1944 and 1945 were also used.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE JEWRY OF SZEGED

Szeged’s Jewish community in Hungary was established over two centuries ago and has a rich cultural and historical heritage. Besides the interruption that the Holocaust imposed on the community between the end of June and October 1944, the Szeged Jewish Community is one of the congregations of rural Hungary that has continued its operations since Jewish religious life could start again in the autumn of 1944. This is probably one of the reasons why many documents in the archive of the congregation, as well as some material goods, still remain in the possession of the Community.

The written history of the Jewry of Szeged starts in 1785, although there were probably Jews who temporarily stayed in the town before this date.[5] The highest number of members in the community was in 1920: according to the census of that year, there were 6,954 Jews residing in Szeged.[6] In 1930, this number decreased to 5,560 people. Despite this decrease, the third-biggest Jewish community in the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary lived in Szeged.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Hungary ensured complete legal and religious equality for Jews living in the country, thus resulting in the Hungarian Jewry becoming strongly assimilated. Before the Second World War, some rights previously given to Jewry were gradually taken back. As a result of the anti-Jewish laws passed between 1920 and 1941, the former emancipation was overturned, Hungarian Jews became persecuted, and their social status was reduced.[7]

It is necessary to mention that the origins of fascism in Hungary can be traced back to Szeged in 1919, when right-wing radicals developed the Szeged Idea (Hun. Szegedi gondolat), which centred around the belief that Hungary had been betrayed in the First World War by communists and Jews. The Szeged Idea called for a war against these perceived traitors, while also promoting Hungarian nationalism, an economic “third way”, and a strong state. Led by Gyula Gömbös, its followers endorsed violence as a legitimate tool of statecraft and adopted fascist policies, including corporatism and racial doctrines. The Szeged Idea aimed to promote a national awakening and a Christian discourse. The idea supported the passage of further anti-Jewish laws and was the driving force behind the numerus clausus, which restricted the number of Jews admitted to higher education.[8] Jewish students at the University of Szeged experienced a wave of antisemitism during the 1930s and 1940s. Moreover, after 1941 members of the university’s faculties were targeted due to their Jewish background. Calls for “cleansing”, thus introducing numerus nullus at the University of Szeged, were made in the press and at student gatherings, resulting in the decision of the University Council in June 1942 not to admit Jewish students into the institution in the following academic year.[9] This decision aimed to achieve “complete de-Judaization of the university” within three years.[10] Finally, this whole process accumulated in the horrors of the Second World War and its events in Hungary.

Similarly to other Jewish populations in Europe, thousands of Jewish citizens from Szeged were killed during the Holocaust. On 19 March 1944, the Germans occupied Hungary. As Tim Cole points out, this occupation was unusual, given that it amounted to the occupation of an ally. From mid-April of the same year, Jews were forced to wear a yellow star; ghettos were established in the major Hungarian towns and villages, and from mid-May the deportation of Hungarian Jewry began.[11] As a major regional town in southern Hungary, Szeged was the main deportation centre for the surrounding towns and villages, parts of current northern Serbia, and the Bačka region, at that time under Hungarian occupation. Approximately 2,000 Jews living near Novi Sad in Bačka were transported via Szeged to Auschwitz or Strasshof between 6 April and May 1944. In June 1944, 8,617 people, including all the Jews from the surrounding settlements and villages, were deported from Szeged in only three days. The first train went to Auschwitz, with most victims being murdered. Due to administrative mistakes during the deportations, the second train ended up being uncoupled, with half going to Auschwitz and half to Strasshof, a labour camp north of Vienna,[12] while the third train was also sent to Strasshof, with most of the Jews surviving. A group of sixty-six people were taken to Budapest. The set-up of the deporting trains is one of the reasons why the Jewry of Szeged was one of the most intact Jewish communities in the Hungarian countryside after the Holocaust, with an exceptionally high survival rate of approximately 60%.[13] This rate also included infants, children, and the elderly, and due to the high number of child survivors, many testimonies and memoirs were written. The case of Szeged is unique in the history of the Hungarian Holocaust because in only a couple of weeks the Hungarian authorities deported 437,000 people who were considered Jewish.[14] In many instances, no records survived of the deportation, either on the Hungarian side or at the destination, which in most cases was Auschwitz. Most of the deported were killed within twenty-four hours of arrival, and no records were kept of their fates.[15]However, the fact that Szeged had a higher rate of survivors does not mean that the dynamics of post-Second World War relations between Jewish returnees and their non-Jewish neighbours were significantly different from elsewhere in Hungary,[16] except for Budapest.[17] Instead, this suggests that the situation in Szeged mirrored the broader trends observed across Hungary, only better documented.

It is essential to mention that antisemitic attitudes and sentiments were present and expressed by non-Jewish residents, who facilitated and accelerated all phases of the extermination. Non-Jews living in Europe and Hungary were active agents for the deportations.[18] It was with the active help of the non-Jewish citizens of Szeged – by definition, neighbours, policemen, gendarmerie, midwives and doctors, carpenters, drivers, and railmen – that the deportation of the local Jews took less than a couple of weeks. Testimonies of Hungarian Holocaust survivors also reveal that those under deportation often “did not hear a German word until the border”.[19]

As historian Omer Bartov explains, testimonies are valuable sources for several reasons, one of which is that they provide otherwise undocumented or unknown details of historical events. Naturally, as testimonies are based on memories and are often said to be subjective accounts of certain events, certain historians tend to avoid using them. Nevertheless, in Bartov’s words, “there is no reason to believe that official contemporary documents written by gestapo, SS, Wehrmacht, or German administrative officials are any more accurate or objective, or any less subjective and biased, than accounts given by those they were trying to kill”.[20] It is clear that, in a number of testimonies, victims hold non-Jewish society, “neighbours”, accountable for at least some of the losses they suffered after their return to their homes. Undeniably, however, non-Jewish individuals (as well as Jewish ones) acted in different ways during and after the deportations, including looting or confiscating properties, items, and even businesses of Jewish individuals – often when the deportations had just begun.

RELATIONS BETWEEN JEWS AND NON-JEWS DURING THE GHETTOIZATION AND DEPORTATION

There were several points of contact between Jews and non-Jews during the ghettoization. Many non-Jewish neighbours played distinct roles, mainly as either bystanders or perpetrators in this process. Confiscating Jewish property in Hungary during the Holocaust was a multi-stage process. Historians have identified three major phases, with non-Jewish neighbours playing an active role in the second. The first phase occurred before the German invasion of Hungary in March 1944 and continued afterwards. During this time, the Sztójay government issued a decree (1.600/1944. M.E.) that required Jews to declare their valuables for confiscation.[21] The second phase began with the ghettoization of Hungarian Jews in April 1944, during which they were allowed to bring only 50 kg of personal belongings to the ghettos. Authorities seized any remaining property and labelled it as “abandoned” property, which was then disposed of by the state, being either used for public purposes or given to non-Jews.[22] As a result of this almost exhaustive state-mandated seizure, so much furniture was accumulated that the storage space allocated for it could no longer accommodate more, and new storage facilities had to be created. While furniture was stored in the Landesberg warehouse in Bocskay Street, large quantities of textiles (bedding and clothing) taken from Jews were stored in the brick factory collection centre.[23] Furniture, carpets, curtains, and other everyday equipment, along with shoes and clothes, were kept at the synagogue, which was never bombed. The final phase of confiscation took place during deportations to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Hungarian gendarmerie, police, and German forces robbed Jewish victims of their last valuables. Many abandoned belongings or real estate became state property or were distributed among or looted by non-Jews.

The so-far unpublished archival documents in the Szeged Jewish Community’s Archives offer a new insight into the experiences of survivors. The importance of being locally rooted has always been an important consideration since the establishment of the Archive as its material is essential for the self-awareness and identity of the local community. The historical records in the archive suggest that while some non-Jewish individuals actively took advantage of the opportunity to claim Jewish property during the period of Jewish persecution, others were passive bystanders who simply watched as Jews were subjected to persecution and forced to relinquish their property. The many claim letters and accounts of non-Jewish individuals that can be found in the Szeged Jewish Archive show that they took advantage of their privileged position to discriminate against Jews. Reports indicate that non-Jewish residents had already requested Jews’ real estate before the deportation.[24] Furthermore, Jews were forced to bear the costs of their relocation, and the Council of the Jewish Community was responsible for covering the expenses of relocating Christians who had to temporarily vacate their homes within the area designated for the ghetto.[25]

Periodical sources from Szeged, such as the daily newspaper, Szegedi Uj Nemzedék (which was a right-wing medium of the time), expressed particular sentiments opposing the ghettoization; the reasons behind this opposition were, however, not connected to the ghettoization per se but rather the districts in which the ghetto was to be located.[26] An article written in May 1944 provides a glimpse into the ghettoization of Jews in Szeged during the Holocaust. The writer asserts that the only absolute solution to the Jewish question is to eliminate the Jews entirely, but in his opinion such a solution was not feasible at that time. The city authorities attempted to implement the solution which they thought was most effective: relocate the Jews from the city centre to designated barracks, hoping to minimize the harm inflicted upon the Christian (non-Jewish) Hungarian population. However, this could not be implemented. The same article expressed empathy for all those opposing the compromise of locating the ghetto in the middle of the town but encouraged its readers to take a long-term perspective on the situation and reminded them that the situation was only temporary: “Our most feared internal enemies have now been fully cornered. So, we must not bemoan or complain about specific regulations that uphold Hungarian interests. The best opportunity is to gather our opponents into a closed, well-demarcated place. We need self-discipline, regardless of a little self-denial or discomfort, to achieve our great goals”.[27]

In addition to the audacity of this, Jewish women were also subjected to the humiliating processes of body searches, with the claims that they may be hiding things when moving to the brick factory. They were forced to undress in front of men, and midwives carried out a body cavity search on them with dirty, ungloved hands. In mid-June, Bishop Hamvas made an urgent appeal to the county governor (Hun. főispán) Aladár Magyary-Kossa, asking him to intervene on behalf of the Jews of Szeged, who were about to be transferred to the local brick factory for wagoning and deportation. Two weeks after the deportation had taken place, in mid-July, Hamvas reported the events in the synagogues of Makó and Szeged to Primate Jusztinián Serédi with indignation: “And another atrocity happened here in Szeged and Makó. There was also a further incident in Szeged, where Jewish women were stripped naked and subjected to carnal searches (per inspectionem vaginae) by midwives and doctors in the presence of men. What is this but a perverted trampling on women’s dignity and modesty?”[28] The body searches[29] were often carried out by neighbours and midwives who had previously encountered the women in question. In the case of a survivor, Irma Spuller (Budapest, 1920 – Budapest, 2018), the midwife who searched her was the same woman who had delivered her daughter ten months earlier. In Irma’s case, however, as she explained, the midwife was relatively humane, and Irma convinced her to foster their dog, which she had to bring to the inspection.[30]

Other examples of the nature of these neighbouring relations were connected to non-Jewish locals, who in many instances aimed to obtain Jewish belongings as soon as the deportation ended. Most members of the public were interested in the distribution of Jewish (mainly movable) property according to the so-called “social criteria”. Many people felt that a historical injustice was being remedied by confiscating foreign property, which was given away for free, and that the easy acquisition of furniture, clothing or even a house would resolve hitherto unsolvable situations and lead to material and social security that previously had seemed impossible to achieve. It occurred to very few people that a social order cannot be deemed stable if it attempts to balance the commonly recognized inequality of wealth with a program that is inhumane towards another group of people (i.e., the Jews) and therefore should be considered sinful according to Christian values. In comparison, the activities of the Szeged Public Supply Office (Szeged város Közellátási Hivatala), which distributed food and “perishable goods” found among Jews, were merely a symptomatic treatment of personal feelings and the social-psychological condition of the masses. First, the distribution of “perishable goods” (food, flour, fat, potatoes, etc.) was planned, followed by the distribution of furniture and furnishings from Jewish property that many non-Jews had claimed.[31]

While the confiscated money and jewellery ended up under the authority of the City of Szeged in order to supplement the financial resources necessary for the continuation of the (by then completely) senseless war, some other movables, such as clothes, furniture and food, were distributed for free via sympathy-generating, tension-relieving social distribution. Other Jewish objects taken into inventory in the ghetto were placed under strict police custody until they were removed, thus preventing them being spontaneously taken.

Even though the houses in the ghetto were locked and under supervision, there must have been attempts to loot them, such as happened in one case in July 1944, when an assistant tile setter was caught after a burglary:

At the police station, the burglar confessed that he had been watching the abandoned Jewish house for some time; when he noticed that no one was ever in the house, he decided to break in. In the burglar’s suitcase, the police found many stolen goods, mainly clothing. After interrogation, the poor assistant tile setter was taken to the prosecutor’s office. According to our information received on Tuesday, Ferenc Zemanovits would be brought to martial law in a few days to receive the punishment he deserves.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the role of local churches as their officials – nuns and priests – can be regarded as neighbours too. According to József Schindler, chief rabbi of Szeged in 1960 (1918, Óbuda – 1963, Szeged), a few nuns went to the brick factory to bring food to the Catholic Jews who were detained there. Undeniably, certain church representatives did try to help those in need. However, these attempts were limited and small in scale.[32]

RETURN TO SZEGED

“We returned to our flat, rang the doorbell politely, and said we had just come back from deportation, saying we used to live here. ‘Now we live here’. they said, and bang, they slammed the door shut. Then we left. Well, what could we have done? That flat had already been rented out to them, or maybe the landlord had rented it out. We did not even know what we had a right to after they had completely excluded us. We had been expelled, they had tried to kill us but failed, and now we dare to come back?”[33]

This excerpt from the memoires of Vera Szöllős, aged 8[34] at the time of her return to Szeged, highlights many aspects of post-war Jewish-gentile relations and the difficulties of restarting life. Vera’s family refrained from reclaiming their flat after the war due to people’s still-prevalent fear and sense of uncertainty, as suggested by their statement:

[We did not try to take it back because] I think there was still a great fear in people, and they did not feel how long their freedom would last. After all, when they left, the surroundings were hostile; so, as far as I understand, they did not try to get the apartment back. There could even have been a sentimental feeling that they had been chased out of their apartment. Thus, they could not chase anybody else out.[35]

Previous studies have shown that after the horrors of the Holocaust the returnees faced several hardships in the countries to which they returned. Of course, those who attempted to flee or were deported could not take their belongings with them. As Edith Molnár, a survivor from Szeged, explained, people tried to give some of their belongings and valuables to their friends and acquaintances in the hope that they would get them back after their return.[36]

For many survivors of the Holocaust, returning to their old homes after the war was, of course, also an extremely difficult emotional experience. While some were able to return to their homes and communities relatively quickly, others found that their belongings had new owners, or their homes had been destroyed, rebuilt, or taken over by new residents. Several testimonies describe this phenomenon in detail. As Lukasz Krzyzanowski points out when discussing Polish returnees, “the returning Jews were in no condition to counteract the results of the two powerful processes taking place before their eyes: the transfer of Jewish property into non-Jewish hands, and the surrender of private property to the state”.[37] This was, of course, very similar in the case of other Jewish communities and other countries, including Hungary and Szeged.

The Soviet army reached Szeged from the south on 11 Octobe 1944,[38] effectively putting the end to a killing campaign of the remaining Jews in the region by the Hungarian Arrow Cross Party.[39] This meant that Szeged was a safe place for Jews after the liberation, and the first Jews – men who were in forced labour in the region and managed to escape – could return to Szeged as early as October 1944. A local survivor, Leó Dénes (born Leó Rottman) (1897, Mohora – 1977, Budapest), must have also played a significant role in protecting Jewish property after October 1944. He was a member of the Szeged Jewish Community and served in forced labour near Szeged until October 1944, when he managed to flee. In the same month, he was appointed as a deputy mayor’s secretary. One of the first things he did was abolish delegitimizing Jewish laws and decrees.[40] In November 1944, he became a councillor, then in January 1945, the deputy mayor of Szeged;[41] thus, he could and did function as a connection between the re-established Szeged Jewish Community (early November 1944) and Szeged City. As a comparison, it is important to note that other parts of the country, including Budapest, were at the same time occupied by the Hungarian Arrow Cross Party after Regent Horthy’s unsuccessful attempt to achieve an armistice.[42]

.jpg)

Ill. 1. Béla Liebmann, soldier in front of the synagogue (January 1945), copyright: Móra Ferenc Museum, Szeged

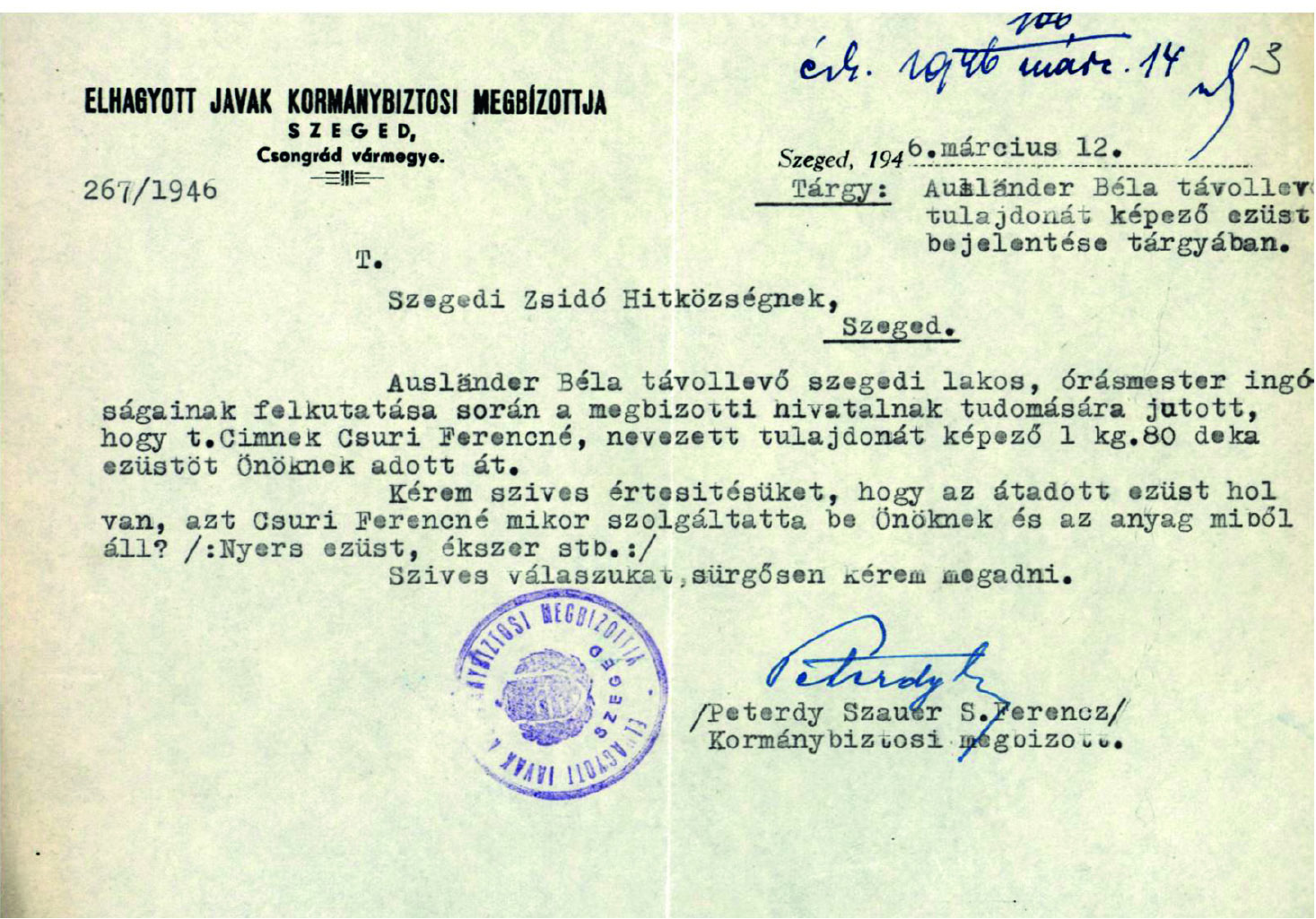

In December 1944, Miklós Béla de Dálnok was appointed the acting Prime Minister of Hungary in Debrecen, liberated by the Soviets, and he established the Government Commission for Abandoned Property in March 1945 (decree no. 727/1945). Its primary goal was to identify, secure, and manage abandoned property left behind by Jews who had been deported or killed during the Holocaust.[43] The commission collected and catalogued abandoned Jewish property, including real estate, household goods, and personal belongings. It also dealt with issues related to inheritance and legal ownership. The commission played a vital role in the post-war reconstruction of Hungary as it was tasked with redistributing abandoned property for public use and aiding in the country’s economic recovery.[44]

Deported Jews started arriving back in Szeged in May 1945. The National Committee for Attending Deportees (Deportáltakat Gondozó Országos Bizottság) informed the Szeged Jewish Community in April 1945 that many deportees from Vienna had survived,[45]thus the city and the community had some time to prepare for their arrival. In April 1945, the leaders of the Szeged Jewish Community were aware that survivors were already on their way to their homes, thus stating that items previously given to non-Jewish residents of Szeged could be requested back. The process of the return can be traced with the help of the Szeged Jewish Community’s Archives as it has – among many other documents – records of correspondence with the local institute, other Jewish communities, survivors’ requests, and lists of items handed over to the local (non-Jewish) population. In most cases, these objects were given to non-Jews, but in some cases they were Jews who had returned to Szeged earlier or who had been, for some reason, exempt from deportation. The archives also include correspondence documenting these processes. In mid-April, the leadership asked for items back from forty-two people, but only nineteen of them fulfilled the request. Seven of those who complied were Jewish.[46]

As a form of reparation, the city organised social movements in partnership with local parties and churches[47] to help the survivors.[48] Despite these efforts and the excellent cooperation, thanks to Leó Dénes, between the Szeged Jewish Community – representing the needs and wishes of the survivors – and the city leaders, and despite the relatively good circumstances regarding the number of survivors as well as the high rate of saved objects, Szeged also faced problems upon the arrival of survivors. There were, for example, many conflicts between returnees and other residents. Testimonies provide us with a detailed account of these matters. György Kármán, a survivor, describes his experiences before and after the Holocaust:

In April [1944], we had to put on the yellow Star [of David]. Me too. […] [The events] followed each other: we had to turn over radios, bicycles – those who had one – they gradually took away our belongings […] they took my grandfather’s paintings; financial officers came and created lists. Needless to say, until this very day, we have not got anything back – no compensation [either].[49]

The shocking realisation that their neighbours had taken Jewish properties hit the survivors upon their return.[50] In her account, Irma Spuller, a young female survivor who had been deported from Szeged, describes how she went from one office to another to regain her family’s apartment. She eventually made a deal with the elderly couple living there, allowing them to stay in one room while she and her family used the other rooms. They had no furniture, so she searched for their belongings that had been left behind in the ghetto:

I managed to find out who had been given my wardrobe, and I took it home. Then I travelled to a farm near Szeged, where a couple supposedly had a whole crate of our bedding, but they said the Russians had taken it. I did not believe them and upon visiting them, I had not even entered the house when I saw their blankets tucked into my duvet cover, and the table was covered with a tablecloth crocheted by my mother. Then they brought out some of my things. The most honest was Nátli, the butcher’s wife, who kept my Grandmother’s ring with brilliants, a copper drink cart, and some beautiful porcelain figurines.[51]

Ill. 2. SzZsHA request, copyright: Szeged Jewish Community’s Archive

Another survivor, Mrs György Landesberg (born Ilona Schiller), spent the first few weeks back in Szeged searching for her belongings, such as her Singer sewing machine and Persian rug.[52] Löw Teri, another female returnee recalled, “…of course, we did not get our apartment back. If I remember correctly, my parents did not want to get a family with a small child evicted from there”, reflecting on the conscious steps survivors would have needed to take to gain their properties back. Instead of returning their property to them automatically, which would have been a responsible action by the authorities, they needed to take steps which often ended with no success.

While positive examples exist, many testimonies account for the negative behaviour of those who awaited the survivors upon their return to Szeged. One such case was described by Jenő Ligeti (1875, Zenta – 1969, Budapest), an elderly journalist who survived the deportation. In his testimony, he explains how their hopes of restarting life had been dashed and how they were disappointed in the lack of justice:

[Upon our return to Szeged] we slept on straw bags on the parquet floor in hotel Bors, but we did not sleep badly because we hoped that we would finally say goodbye to straw bags and other hard, makeshift beds. We were wrong, however, because the welcome we received back home was nothing like what we had hoped for. I should not be unfair, since we were received with great joy by old friends and acquaintances. However, when we wanted to move into our flat and take up our old, abandoned position, it turned out they were not happy to see us back. They even seemed to take it badly that we had survived […]. And there are hundreds of people who are forced to do without stolen furniture, clothes, dishes and other essential necessities of life.[53]

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, Jewish–non-Jewish relations in Szeged were marked by a mixture of tension and cooperation, as exemplified by the positive example of a non-Jewish timber assistant who was willing to testify on behalf of a Jewish survivor seeking the return of his property. This survivor, from whose workshop wood had been stolen to build the ghetto walls in 1944, sought to reclaim his materials in order to re-establish his livelihood.[54] Recognising the injustice of the situation, the non-Jewish assistant offered his support as a witness to this survivor’s claim. This act of solidarity between these two individuals is a poignant example of how post-Holocaust relations between Jews and non-Jews were shaped by a complex interplay of trauma, memory, and the desire for justice and reconciliation. However, cases of non-Jewish individuals’ willingness to support Jewish survivors in their quest for restitution remained scarce and exceptional.

It is essential to mention that confiscation of the Hungarian Jewry’s valuables and property during this period did not start with the Nazis. The responsibility of Hungarian authorities has to be addressed as the process that stripped Jewish citizens of their rights, property, and eventually their lives began well before the Nazi occupation. Moreover, it is also important to recognize that the post-war political situation further contributed to the confiscation of certain goods and properties, including remaining Jewish belongings, this time in the form of nationalization.[55] Some of the losses experienced during this period were also associated with the emotional impact of the missing objects, as these absences made it more difficult for survivors to reestablish themselves and their lives. This phenomenon also decreased their hopes of gaining justice. It is clear that the victims faced tremendous loss in terms of emotional and material aspects of their lives, but what do the sources tell us about their neighbours’ feelings about the situation?

The available sources suggest that discussions around the returnees were filled with antisemitism and indifference towards them and their loss(es). When asked by an interviewer about how he was received by his non-Jewish neighbours, William Farenci, a Holocaust survivor from Szeged, said, “Oh… one was the biggest sváb [Swabian], you know; […] she was the biggest bitch antisemite and wanted to hug and kiss me, and bla-bla. […] Otherwise, the answer is mixed. Half and half. Some of them said ‘There are more of you who came back than went away!’”[56]

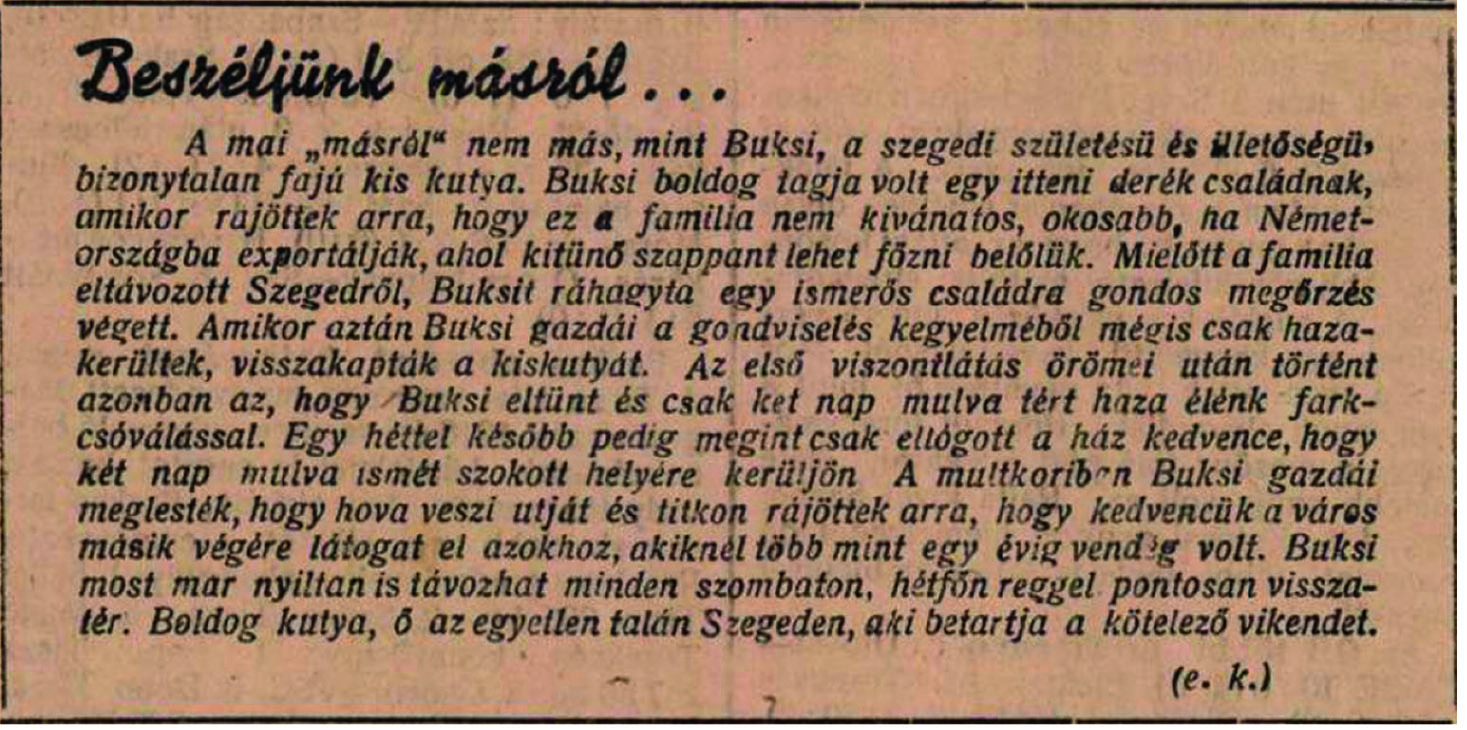

Another example that demonstrates this is an article from April 1946 in a local newspaper, Szeged Népszava. The article tells the story of a dog which found its owners, who had been sent to Germany “where they make excellent soap from them”.[57] The sole fact that a text of this sort could be published gives a clear description of the general public’s attitude concerning the situation.

Ill. 3. Dog advertisement picture, copyright: Arcanum

Ágnes Szigeti (née Weiss, b. 1925, Szeged) recounted her experience of returning to Szeged after the war when an interviewer asked how they were welcomed back, stating:

Rather badly. They wondered why we were alive; they did not want to admit that we had left our things with them, and they did not want to help us in any way. It was such a bizarre feeling that somehow we had not found the old surroundings that we had left; we were looking for [the life] that we had left, and it was not there anymore. […] It was not the same people we had left living in that house, […] it was completely strange people living there; they did not even know us. In one of the flats, for example, a writer was living there; he was surprised, saying that he thought that all the Jews had been exterminated or killed, that he was surprised that we had come back at all. The tenants with whom we were living were doing everything they could to get us out of there as quickly as possible, but we just could not leave.[58]

Of course, there were also examples of Jewish survivors having problems with both the Jewish and non-Jewish populations. It is worth quoting from a letter written by Alfréd Aczél in July 1945 to the Jewish Community, in which he demands justice from the Jewish community:

You are probably aware that by the time the deportees came home, my daughters had found nothing of my belongings left behind except a sideboard, the removal of which – because of financial hardship at the moment – is currently not possible. The current tenant refuses to leave my flat. I also found a white wardrobe, which Mrs Sarolta Fischhof declared to be hers and took away, and a sewing machine, of which my ownership was acknowledged, but it has not been released to me with the statement “she does not need it”.[59]

There are documented cases where enforcement had to be ordered because non-Jewish tenants refused to vacate properties previously owned by Jews who had returned from deportation. This suggests that not all members of the non-Jewish population were willing to adhere to the legal and moral imperatives of the time.[60] In all cases, the rules for the allocation of housing were administered by the Jewish Community. In April 1945, in cooperation with the city administration, guidelines were drawn up to help returnees find housing as quickly as possible. According to these guidelines, applications would be processed without delay, all appeals from temporary (non-Jewish) owners or residents would be declined, and the city authorities would use all means to facilitate occupancy (i.e., non-Jewish tenants could be evicted by force). Non-Jewish tenants were not allowed to delay by appealing. At the same time, ten people were issued official housing inspector cards and provided with official documents allowing them to proceed in these cases.[61]

Not only adults had to face abandonment by the non-Jewish residents of Szeged.[62] Vera Pick, born in 1933 in Vienna, is the granddaughter of Márk Pick, the founder of the Pick Salami factory. She was deported with her parents and lost her father in Bergen Belsen in February 1945. At the time of her return to Szeged, she was 12 years old – old enough to remember the bitter realisation that her family’s flat had been occupied by others who openly stated that their return was not at all expected or celebrated:

My mother came back six weeks later with swollen legs, weighing 46 kilos, and very weak, but with a strong will to survive. We got back, this time on a proper train to Budapest, Hungary, and a few days later back to where we had started from, namely Szeged. That was on 22 June 1945. People looked at us in amazement and declared, “We really did not expect to see you again”. What a great greeting that was! Once again, going back to our home, we found nothing but the four walls – not a chair, not a bed, no cutlery, no plates. We had to start all over finding the basics, and at that time we had no money. Some things were piled up in the schoolyard and the synagogue, and a man distributed the necessities to people. I remember that my mother burned the wooden pillars of our bunker for firewood.[63]

Even items of small value were often taken and kept by non-Jewish individuals, who may have seen them as an opportunity to enrich themselves. This phenomenon is reflected in the requests kept in the Szeged Jewish Archive. The requests in many cases were formulated by non-Jews who asked for everyday items like clothing and household goods, but also larger items like homes, jewellery and businesses. In several cases, non-Jewish individuals refused to return items of even small value. Edith Molnár, for example, recalled that her father asked a non-Jewish “friend” of his to safeguard a ring with a small diamond in it. When Edith returned and requested the ring back, the man told her that the Germans had taken it, while she could see it on his finger. She also described a sense of post-war apathy among fellow Jewish survivors, whose struggles and trauma overshadowed their ability to provide support and empathy to their relatives. The enormity of the trauma they had experienced seemed to have left them feeling emotionally depleted and overwhelmed, making it challenging for them to assist others, even their family members.[64]

The fact that people were permitted to enter the homes of their neighbours and remove their belongings, and the government has never investigated how widely the enormous wealth and quantity of items of over 400,000 Jews were dispersed – these have had a long-lasting effect on Hungarian society. The failure to return confiscated property to Jewish owners after the war was a significant injustice, one that compounded the trauma and loss experienced by survivors and inhibited reconciliation with the local non-Jewish society. Appropriating Jewish belongings was a transnational phenomenon in several countries under German occupation.[65]

The Szeged Jewish Community kept extensive records of non-Jewish individuals who borrowed items and were required to return them upon the request of their owners. These documents reveal the tensions that existed between Jewish owners and those non-Jewish locals who took from them, such as in the case of a local non-Jewish resident who repainted a piece of unspecified “Jewish furniture” (Hun. zsidóbútor) and took away a piano. The records also show that bomb victims and other residents received some of these ‘borrowed’ items, including items that by no means can be regarded as essential, such as a cake utensil set, a mirror, and silver candlesticks. The fact that non-essential items were taken from Jewish owners undermines the argument that only essential items were taken from them.

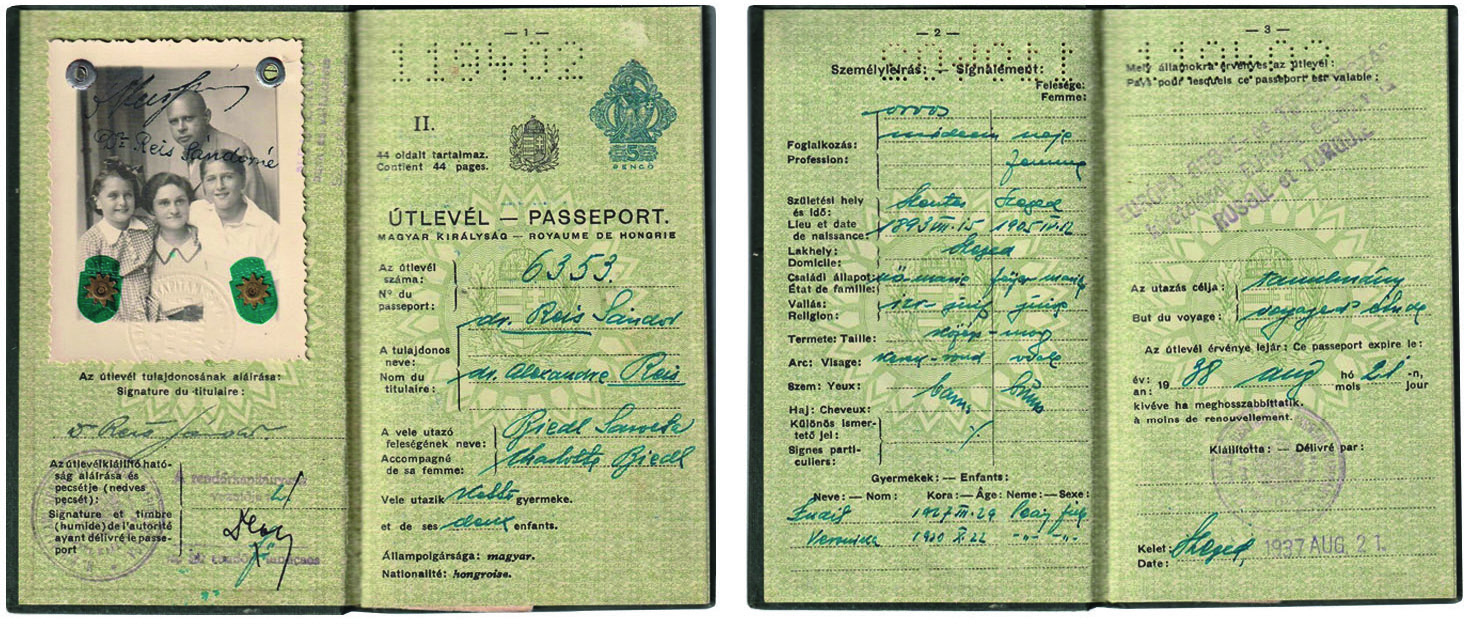

Starting from November 1944, newspapers were full of announcements by which survivors tried to get and, in some cases, repurchase their properties. Occasionally, the objects they longed for did not even have monetary value: Sándor Reis, a dentist from Szeged, offered 500 pengő to get the photographic films of his family back.[66] A couple of months earlier, he had attempted to get his clothes back: “I ask all those who took my winter coat, overcoat, bed linen and covers with the initials B. S. and R. S. from the apartment on the first floor of the ghetto at 10 Korona Street 1st floor, as well as my children’s and my wife’s belongings, to bring them back to Dr Sándor Reis, dentist, at 61 Tisza Lajos Boulevard ”.[67]

Ill. 4. Reis family, passport picture, copyright: Reisz family

As briefly indicated before, there were also positive stories in the immediate post-war period in Szeged regarding relations between Jewish survivors and their non-Jewish neighbours. We know of a few instances when Jewish survivors returned to their homes and were met with kindness and assistance from fellow citizens who were eager to help them rebuild their lives. This support was a significant departure from the wartime period, when Jews in Hungary were subjected to persecution and discrimination. The willingness of non-Jewish residents to extend a helping hand demonstrated a sense of compassion and empathy towards their fellow citizens.

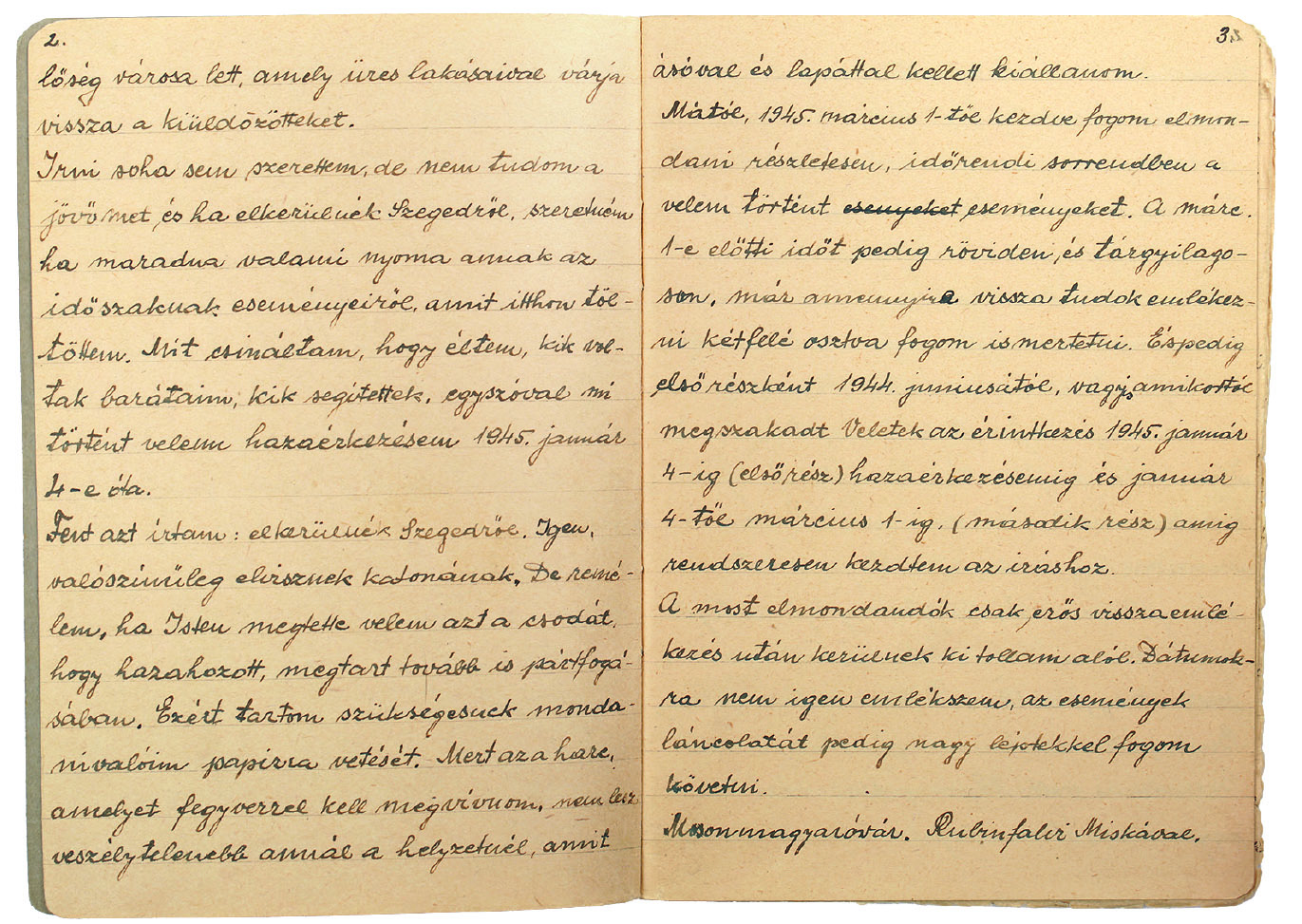

Béla Seifmann’s return to Szeged in early 1945 after months of forced labour was marked by mixed reactions from his neighbours. As a young Jewish man, he encountered both helpful and unhelpful neighbours in his community. He remembered the first days of his return and the relations with the old network upon returning. He stayed with an old friend of his, a young girl, Emmy Feuer, who was exempt from deportation because she had a Christian mother:

I’m staying at Emmy’s place for ten days and [getting] complete rest. I get nothing from Aunt Kenderesi. Aunt Raffai has some things for me, plus 200 pengő. No one responds to my newspaper advertisement either.[68] I get an allowance from Joint.[69] I am not working yet. […] I have good, cheap meals at Aunt Kati’s. I brought a few pieces of furniture from the ghetto and [as a result I got] reported for theft.[70]

Ill. 5. A page of the diary of Béla Seifmann, copyright: Szeged Jewish Community’s Archive

Amidst the turmoil and devastation of the Holocaust, many Jews found themselves in complete despair, stripped of their homes, possessions, and even their loved ones. When reflecting on the harsh months after the Holocaust, Teri Löw, aged 14, granddaughter of chief rabbi Immánuel Löw (1854, Szeged – 1944, Budapest), highlights the crucial role played by Joint in ensuring their survival: “We owe it to Joint that they provided us with food during the first few months. I remember receiving packages from abroad, which contained clothing, food, Hershey’s chocolate and cocoa”.[71]

HOLDING THE LOOTERS ACCOUNTABLE?

After the war, cases of attempts to hide assets involving non-Jewish neighbours came to light. In one such case, a merchant named Béla Iritz from Szeged hid his valuable jewellery in a jar before his deportation and asked an acquaintance to keep it in a safe place. However, when he returned home, he discovered that the jar had been removed from the coal cellar where it was hidden, and its contents worth around half a million pengős were missing. A group of detectives conducted a thorough investigation, which led to the suspicion that the haulier who removed the coal and his workers had discovered the jewellery and kept it. One of the haulier’s employees, János Liptai, eventually reported himself as an “honest finder” and returned several pieces of jewellery. However, the victim claimed that this was only some of the contents of the jar, and the police continued to detain Liptai and search for the missing jewellery and his possible accomplices.[72]

Legal disputes arose after the Second World War in attempts to punish those who had betrayed their Jewish neighbours in 1944. When the Germans entered the country in the spring of 1944, even experienced Gestapo leaders were surprised by the enormous number of denunciations and reports flooding their desks. An article written in September 1945 regarding the Szeged People’s Court revealed the overwhelming number of reports and denunciations that had inundated German authorities’ desks during the spring of 1944. In one case, Mr József Kopasz, aged 69, was held accountable for her extensive report to the Gestapo. She complained to the German authorities about her neighbours for the “crime” of hiding Jewish property. A witness stated that the accused’s hatred had contaminated the air of the entire house, and she had been plotting against the Jewish residents for years.[73]

It is essential to point out that while in some cases the “infrastructure” that may have allowed confiscated and looted possessions and properties to be returned to their Jewish owners – in addition to practical aspects, such as being in need of elementary everyday items – the post-traumatic experiences of the war cannot be overlooked in these processes. Victims were not only heavily burdened by their emotional trauma but were also struggling with a loss of trust in those they had considered their friends before the Second World War. Lacking such trust and fearing the potential results of inquiring about their lost possessions and properties may often have led them to give up on claiming their objects back, thus contributing to inhibited reconciliation with the local non-Jewish society. These instances also highlight that there were no systematic investigations into looted goods and there was a lack of organized efforts to achieve recovery and compensation.

CONCLUSION

This study on Jewish–non-Jewish relations in Szeged provides a glimpse into the complex dynamics that emerged between these two communities during and after the Second World War. What is particularly interesting about the Szeged case is the high number of survivors of all ages, which – with the help of documents in the archives of the Szeged Jewish Community – enables extensive exploration of these relations through personal accounts. In this study, the authors have aimed to give a comprehensive overview of the history of the Jews in Szeged and briefly present the roots of antisemitic sentiments in the region, the relationship between Jews and non-Jewish society, and the experiences of the survivors upon returning.

Through a wealth of primary sources such as letters, requests, testimonies from survivors, and newspaper articles, this study vividly illustrates the challenges faced by Jewish survivors during and after their repatriation to Szeged. It highlights that the confiscation and looting of property were not only conducted by the German army but also involved Hungarian authorities and the broader population, underscoring the collective responsibility in discussing the Holocaust in Hungary.

The loss of property and family members and the trauma of the Holocaust created a challenging environment that required immense resilience and perseverance to overcome. Survivors in Szeged, similarly to everywhere else, had to face several challenges, including struggles to reclaim confiscated property and efforts to reintegrate into the community with their pre-war neighbours, who – in many cases – not only abandoned them but actively persecuted them.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

SOURCES

Deportáltakat Gondozó Országos Bizottság, ‘Jegyzőkönyv 1792’ [Testimony of Mrs Ferenc Klein (no. 1792)] <http://degob.hu/?showjk=1792> [accessed 22 March 2023]

Deportáltakat Gondozó Országos Bizottság, ‘Jegyzőkönyv 3555’ [Testimony of Jenő Ligeti (no. 3555)] <http://degob.hu/?showjk=3555> [accessed 29 March 2023]

Deportáltakat Gondozó Országos Bizottság, ‘Jegyzőkönyv 3576’ [Testimony of Arnold Kármán (no. 3576)] <http://degob.hu/?showjk=3576> [accessed 29 March 2023]

SzJCA, documents of 1945, 1945/118, 1945/119, 1945/120, 1945/262, 1945/429

Testimony of Ágnes Szigeti, USC Shoah foundation, interview ID: 51018

Testimony of Edith Molnár. USC Shoah foundation, interview ID: 22798

Testimony of Ferencné Lovász. USC Shoah Foundation, interview ID: 50591

Testimony of Veronika Szöllős, <https://www.centropa.org/hu/biography/szollos-veronika> [accessed on 24 January 2025]

Testimony of William Farenci, USC Shoah foundation, interview ID: 18631

TheJDCArchives, JDC Archives Fellowship Lecture – Dóra Pataricza, online video recording, YouTube, 5 May 2021 <https://youtu.be/jmgAdeLAOU4?si=M2kt-mxS7AbjDSoY> [accessed on 24 January 2025]

A Magyar Királyi Kormány 1919-22. évi működéséről és az ország közállapotairól szóló jelentés és statisztikai évkönyv (Budapest: Atheneum, 1926)

A Magyar Királyi Kormány 1931. évi működéséről és az ország közállapotairól szóló jelentés és statisztikai évkönyv (Budapest: Atheneum, 1933)

Auslander, Leora, ‘Coming Home? Jews in Postwar Paris’, Journal of Contemporary History, 40.2 (2005), 237–59 <https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009405051552>

‘Az egyetemi ifjuság lapja a szegedi egyetem zsidótlanitásáról’, Délmagyarország, 26 June 1942,

Bartov, Omer, ‘Wartime Lies and Other Testimonies: Jewish-Christian Relations in Buczacz, 1939–1944’, East European Politics and Societies, 25.3 (2011), 486–511

<https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325411398918>

‘Besúgók napja a szegedi népbíróságon’, Szegedi Népszava, 22 September 1945,

Bognár, Irma, Adjanak hálát a sorsnak. Deportálásunk története (Budapest: Sík, 2004)

Braham, Randolph L., and Zoltán Tibori Szabó (eds), A magyarországi holokauszt földrajzi enciklopédiája, 3 vols (Budapest: Park, 2007)

‘Dénes Leó Szeged polgármestere’, Szegedi Népszava, 23 August 1945, 1

‘Dénes Leó’, Ágnes Kenyeres and Sándor Bortnyik, Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1967)

Cantillon, Lauren, ‘Dis-covering Overlooked Narratives of Sexual(ised) Violence: Jewish Women’s Stories of ‘Body Searches’ in the Ghetto Spaces of Occupied Hungary During the Holocaust’, Conference paper at Precarious Archives, Precarious Voices: Expanding Jewish Narratives from the Margins. Simon Wiesenthal Institut, Vienna, Austria, 17–19 November 2021

Cole, Tim, ‘Writing “Bystanders” into Holocaust History in More Active Ways: “Non-Jewish” Engagement with Ghettoisation, Hungary 1944’, Holocaust Studies, 11 (2005), 55–74 <https://doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2005.11087139>

e.k., ‘Beszéljünk másról’, Szegedi Népszava, 2 April 1946

Gara, Vera, Least-Expected Heroes of the Holocaust: Personal Memories (Ottawa: Vera Gara, 2011)

Hondius, Dienke, ‘A Cold Reception: Holocaust Survivors in the Netherlands and Their Return’, Patterns of Prejudice, 28 (1994), 47–65 <https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.1994.9970119>

Kádár, Gábor, and Zoltán Vági, Aranyvonat: fejezetek a zsidó vagyon történetéből (Budapest: Osiris, 2001)

Kádár, Gábor, and Zoltán Vági, Hullarablás. A magyar zsidók gazdasági megsemmisítése (Budapest: Hannah Arendt Egyesület – Jaffa Kiadó, 2005)

Karady, Victor, ‘The restructuring of the academic marketplace in Hungary’, in The numerus clausus in Hungary. Studies on the First Anti-Jewish Law and Academic Anti-Semitism, Modern Central Europe, ed. by Victor Karady and Peter Tibor Nagy (Research Reports on Central European History; Vol 1.) 112–35

Karsai, Elek, and Ilona Benoschofsky (eds), Vádirat a Nácizmus Ellen: Dokumentumok a Magyarországi Zsidóüldözés Történetéhez. 1944. Május 26–1944. Október 15: A Budapesti Zsidóság Deportálásának Felfü̈ggesztése (Budapest: A Magyar Izraelitàk Országos Képviselete, 1967)

Klacsmann, Borbála, ‘Neglected Restitution: The Relations of the Government Commission for Abandoned Property and the Hungarian Jews, 1945–1948’, Hungarian Historical Review, 9.3 (2020), 512–29

Klacsmann, Borbála, ‘Abandoned, confiscated, and stolen property: Jewish-Gentile relations in Hungary as reflected in restitution letters’, Holocaust Studies, 23 (2016), 133–48 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2016.1209836>

Klacsmann, Borbála, ‘Elhanyagolt kárpótlás: Az Elhagyott Javak Kormánybiztossága és a magyar zsidók kapcsolata’ (1945–1948), Századok, (2019), 715–30

Kovács, Éva, András Lénárt and Anna Lujza Szász, ‘Oral History Collections on the Holocaust in Hungary’, S:I.M.O.N. – Shoah: Intervention. Methods. Documentation, 1 (2014), 48–66

Krzyzanowski, Lukasz, Ghost Citizens: Jewish Return to a Postwar City (Cambridge–London: Harvard University Press, 2020)

Lányi, Pál, ‘Szegedi gettóládánk kifosztása’ (Budapest, 2022) (unpublished manuscript)

Löw, Immánuel and Zsigmond Kulinyi, A szegedi zsidók 1785-től 1885-ig (Szeged: Traub, 1885)

Marjanucz, László, ‘A szegedi zsidó polgárság műértékeinek sorsa a deportálások idején’, A Móra Ferenc Múzeum Évkönyve: Studia Historica, 1 (1995)

Molnár, Judit, ‘Embermentés vagy árulás? A Kasztner-akció szegedi vonatkozásai’, in Szeged – Strasshof – Szeged. Tények és emlékek a Bécsben és környékén “jégre tett” szegedi deportáltakról 1944–1947, ed. by Kinga Frojimovics and Judit Molnár (Szeged: SZTE ÁJTK Politológiai Tanszék – Szegedi Magyar-Izraeli Baráti Társaság, 2021)

Molnár, Judit, ‘Véletlenek. 15 ezer főnyi “munkaerő-szállítmány” sorsa 1944 júniusában’, in Szeged – Strasshof – Szeged. Tények és emlékek a Bécsben és környékén “jégre tett” szegedi deportáltakról 1944–1947, ed. by Kinga Frojimovics and Judit Molnár (Szeged: SZTE ÁJTK Politológiai Tanszék – Szegedi Magyar-Izraeli Baráti Társaság, 2021)

Pálfy, György, ‘A városházán’, Délmagyarország, 11 October 1969, 5

Pataricza, Dóra and András Lénárt (eds), Seifmann Béla visszaemlékezése. Egy munkaszolgálatos naplója (Budapest: HDKE, 2023)

Pataricza, Dóra and Mercédesz Czimbalmos, ‘Post-war narratives of the conversion in the shadow of death – A case study from Szeged, Hungary,’ in The Churches in Eastern and Southeastern Europe and the “Jewish Question” during the First Half of the 20th Century. Thematic Issue in Eastern Church Identities, ed. by Marian Pătru (Brill, forthcoming)

Pataricza, Dóra, ‘“The first time I saw my father cry” – Children’s accounts of the deportations from Szeged’, in Jewish Culture and History, The Usage of Ego-Documents in Jewish Historical Research, 24.2 (2023) <https://doi.org/10.1080/1462169X.2023.2202085>

Peresztegi, Ágnes, ‘Reparation and Compensation in Hungary 1945–2003’, The Holocaust in Hungary: A European Perspective, ed. by Judit Molnár (Budapest: Balassi Kiadó, 2005), pp. 677–84

Rees, Laurence, Holocaust. A new history (London: Viking, 2017)

Ritter, Andrea, ‘Escape from Traumas: Emigration and Hungarian Jewish Identity After the Holocaust’, American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 79.4 (2019), 577–93

<https://doi.org/10.1057/s11231-019-09223-0>

Sárközi, István, ‘Adalékok Dénes Leó munkásmozgalmi és közéleti tevékenységéhez

(1919-1977)’, Móra Ferenc Múzeum Évkönyve, 81.1 (1980)

Szegedi Népszava, 9 June 1945, 2

Szegedi Népszava, 2 April 1946

Ungváry Krisztián, Magyarország a második világháborúban (Budapest: Kossuth, 2010)

Vonyó, József, ‘Gömbös Gyula és a hatalom. Egy politikussá lett katonatiszt’ (Akadémiai doktori értekezés, Pécs, 2015)

Waligórska, Magdalena, and Ina Sorkina, ‘The Second Life of Jewish Belongings-Jewish Personal Objects and Their Afterlives in the Polish and Belarusian Post-Holocaust Shtetls’, Holocaust Studies, 23.3 (2022): 341–62 <https://doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2022.2047292>

ILLUSTRATIONS:

Béla Liebmann, soldier in front of the synagogue (January 1945), copyright: Móra Ferenc Museum, Szeged

SzZsHA request, copyright: Szeged Jewish Community’s Archive

Dog advertisement picture, copyright: Arcanum

Reis family, passport picture, copyright: Reisz family

A page of the diary of Béla Seifmann, copyright: Szeged Jewish Community’s Archive

[1] Our definition of neighbours is individuals who live in close physical proximity to another individual, such as someone who resides in the same building, on the same street, or in the same neighbourhood. In our understanding, in the broad sense ‘neighbour’ also refers to a member of the same community or town. It is important to emphasize that this definition extends to include local policemen and authorities who were often involved in the deportations of Jewish residents, despite potentially having been neighbours before.

[2] For further reading: Dov Levin, ‘On the relations between the Baltic peoples and their Jewish neighbours before, during and after World War II’, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 5.1 (1990), 53–66

<https://doi.org/10.1093/hgs/5.1.53>; Mediating Polish-Jewish Relations after the Holocaust, ed. by Dorota Glowacka and Joanna Zylinska (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2007); Omer Bartov, ‘Wartime Lies and Other Testimonies: Jewish-Christian Relations in Buczacz, 1939–1944’, East European Politics and Societies, 25.3 (2011), 486–511 <https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325411398918>.

[3] Magdalena Waligórska and Ina Sorkina, ‘The Second Life of Jewish Belongings – Jewish Personal Objects and Their Afterlives in the Polish and Belarusian Post-Holocaust Shtetls’, Holocaust Studies ahead-of-print, (2022), pp. 1–22 <https://doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2022.2047292>.

[4] Dienke Hondius, ‘A Cold Reception: Holocaust Survivors in the Netherlands and Their Return’, Patterns of Prejudice, 28.1 (1994), 47–65 <https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.1994.9970119>; Monika Vrzgulova, ‘The Memory of the Return of Slovak Holocaust Survivors in Jewish and Non-Jewish Testimonies’, Judaica Bohemiae, 53.2 (2018); Dan Michman, ‘Commonalities and Peculiarities of the Return to Life of Holocaust Survivors in Their Home Countries: The Dutch and Greek Cases in Context’, Historein, 18 (2019) <https://doi.org/10.12681/historein.14321>.

[5] Immánuel Löw and Zsigmond Kulinyi, A szegedi zsidók 1785-től 1885-ig (Szeged: Traub, 1885), pp. XVI–XVII.

[6] A Magyar Királyi Kormány 1919–22. évi működéséről és az ország közállapotairól szóló jelentés és statisztikai évkönyv (Budapest: Atheneum, 1926), p. 11.

[7] Andrea Ritter, ‘Escape from Traumas: Emigration and Hungarian Jewish Identity After the Holocaust’, The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 79.4 (2019), 577–93 (p. 579) <https://doi.org/10.1057/s11231-019-09223-0>.

[8] József Vonyó, ‘Gömbös Gyula és a hatalom. Egy politikussá lett katonatiszt’, PhD thesis, Pécs, 2015, p. 132.

[9] ‘Az egyetemi ifjuság lapja a szegedi egyetem zsidótlanitásáról’, Délmagyarország, 26 June 1942, p. 5.

[10] Victor Karady, ‘The restructuring of the academic marketplace in Hungary’, in The numerus clausus in Hungary. Studies on the First Anti-Jewish Law and Academic Anti-Semitism in Modern Central Europe, ed. by Victor Karady and Peter Tibor Nagy (Research Reports on Central European History; vol 1.), pp. 112–23.

[11] Tim Cole, ‘Writing “Bystanders” into Holocaust History in More Active Ways: “Non-Jewish” Engagement with Ghettoisation, Hungary 1944’, Holocaust Studies, 11 (2005), 62–63 <https://doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2005.11087139>.

[12] Judit Molnár, ‘Embermentés vagy árulás? A Kasztner-akció szegedi vonatkozásai’ and Judit Molnár, ‘Véletlenek. 15 ezer főnyi “munkaerő-szállítmány” sorsa 1944 júniusában’, in Szeged – Strasshof – Szeged. Tények és emlékek a Bécsben és környékén „jégre tett” szegedi deportáltakról 1944–1947, ed. by Kinga Frojimovics and Judit Molnár (Szeged: SZTE ÁJTK Politológiai Tanszék – Szegedi Magyar-Izraeli Baráti Társaság, 2021).

[13] The JDCArchives, JDC Archives Fellowship Lecture – Dóra Pataricza, online video recording, YouTube, 5 May 2021 <https://youtu.be/jmgAdeLAOU4?si=M2kt-mxS7AbjDSoY> [accessed on 11 November 2023].

[14] A magyarországi holokauszt földrajzi enciklopédiája, ed. by Randolph L. Braham and Zoltán Tibori Szabó, 3 vols (Budapest: Park, 2007), I, pp. 7–92.

[15] Laurence Rees, The Holocaust. A new history (London: Viking, 2017), p. 392.

[16] See e.g., Borbála Klacsmann, ‘Abandoned, confiscated, and stolen property: Jewish-Gentile relations in Hungary as reflected in restitution letters’, Holocaust Studies, 23 (2016), 133–48 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2016.1209836>.

[17] As the deportations started in the Hungarian countryside and were eventually stopped in early July, the majority of the Jewry of Budapest survived the Shoah.

[18] Cole, ‘Writing “Bystanders”’, p. 55.

[19] E.g., in the testimony of Mrs Ferenc Klein: “We were handed over to the Germans in Magyaróvár”, degob testimony no. 1792 <http://degob.hu/index.php?showjk=1792> [accessed on 11 November 2023].

[20] Bartov, ‘Wartime lies’, p. 488.

[21] It is important to mention that between 29 March and 15 October 1944, the Sztójay government issued over 100 decrees concerning Jews. Such decrees included banning Jews from employing non-Jews in Jewish households (1.200/1944.M.E.), obligatory reporting of Jewish citizens’ phones, cars, and radios (1.300/1944.M.E.), and forcing Jewish citizens to take housing designated to them (1.610/1944.M.E.).

[22] Klacsmann, ‘Abandoned, confiscated, and stolen property’, pp. 3–4. Borbála Klacsmann has written several articles in Hungarian and English on confiscated Jewish property and an extensive case study on the fate of these objects and their owners in Újpest and Monor.

[23] László Marjanucz, ‘A szegedi zsidó polgárság műértékeinek sorsa a deportálások idején’, A Móra Ferenc Múzeum Évkönyve: Studia Historica, 1 (1995), 243. On the fate of the most valuable looted properties of Hungarian Jewry, see Gábor Kádár and Zoltán Vági, Aranyvonat: Fejezetek a Zsidó Vagyon Történetéből. (Budapest: Osiris, 2001).

[24] Szeged sz. Kir. város polgármesterétől. File number: 27273/1944; written on 26 May 1944. Subject: Decision about the Jewish houses. SzJCA, documents of 1945, indexing in progress.

[25] Ibid. File number: 44877/1944 III-a sz. Subject: Reimbursement of expenses of Christians who have moved out of the territory of the ghetto. SzJCA, SzJCA, documents of 1945, indexing in progress.

[26] [Vásárhelyi] Népújság, 8 May 1944, p. 3., and Szegedi Uj Nemzedek, 3 May 1944; 5 May 1944.

[27] Szegedi Uj Nemzedék, 5 May 1944, p. 4., Quoted by Cole, Writing ‘Bystanders’, pp. 64–65.

[28] ‘Hamvas levele Serédihez’, in Vádirat a Nácizmus Ellen: Dokumentumok a Magyarországi Zsidóüldözés Történetéhez. 1944. Május 26.–1944. Október 15: A Budapesti Zsidóság Deportálásának Felfü̈ggesztése, ed. by Elek Karsai and Ilona Benoschofsky (Budapest: A Magyar Izraelitàk Országos Képviselete, 1967), III, pp. 206–07.

[29] Lauren Cantillon, ‘Dis-covering Overlooked Narratives of Sexual(ised) Violence: Jewish Women’s Stories of ‘Body Searches’ in the Ghetto Spaces of Occupied Hungary During the Holocaust’, Conference paper at Precarious Archives, Precarious Voices: Expanding Jewish Narratives from the Margins, Simon Wiesenthal Institut, Vienna, Austria, 17–19 November 2021.

[30] Irma Bognár, Adjanak hálát a sorsnak, (Budapest: Sík, 2004), p. 13

[31] Marjanucz, ‘A szegedi zsidó polgárság műértékeinek sorsa’, p. 250.

[32] Dóra Pataricza and Mercédesz Czimbalmos, ‘Post-war narratives of the conversion in the shadow of death – A case study from Szeged, Hungary’, in The Churches in Eastern and Southeastern Europe and the “Jewish Question” during the First Half of the 20th Century. Thematic Issue in Eastern Church Identities, ed. by Marian Pătru (Brill, forthcoming).

[33] Testimony of Veronika Szöllős: ‘Szöllős Veronika’, Centropa, [n.d.] <https://www.centropa.org/hu/biography/szollos-veronika> [accessed on 24 January 2025].

[34] It is important to note that survivors who were children at the time of the Holocaust may not remember every detail or have understood the complexity at a very young age. Yet, their testimonies are essential (Boaz Cohen and Rita Horváth, ‘Young Witnesses in the DP camps: Children’s Holocaust testimony in context’, Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 11 (2012), 103–25 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14725886.2012.646704>).

In the case of Veronika Szöllős, she was in psychotherapy in her fifties, which helped to bring back her memories (<https://www.centropa.org/hu/biography/szollos-veronika>).

[35] Testimony of Vera Szöllős, USC Shoah Foundation, interview ID: 50591, segment 43–44.

[36] Testimony of Edith Molnár, USC Shoah Foundation, interview ID: 22798, segment 224.

[37] Lukasz Krzyzanowski, Ghost Citizens: Jewish Return to a Postwar City (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2020), p. 264.

[38] György Pálfy, ‘A városházán’, Délmagyarország, 11 October 1969, p. 5.

[39] The Arrow Cross Party was a far-right Hungarian ultranationalist party led by Ferenc Szálasi.

[40] István Sárközi, ‘Adalékok Dénes Leó munkásmozgalmi és közéleti tevékenységéhez (1919–1977)’, Móra Ferenc Múzeum Évkönyve, 1 (1980–1981), 330; and ‘Dénes Leó Szeged polgármestere’, in Szegedi Népszava, 23 August 1945, p. 1.

[41] Entry: ‘Dénes Leó’, in Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon, ed. by Ágnes Kenyeres and Sándor Bortnyik (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1967).

[42] Krisztián Ungváry, Magyarország a második világháborúban (Budapest: Kossuth, 2010). For more, see id., Kiugrás a történelemből – Horthy Miklós a világpolitika színpadán (Budapest: Open Books, 2022).

[43] Borbála Klacsmann, ‘Elhanyagolt kárpótlás: Az Elhagyott Javak Kormánybiztossága és a magyar zsidók kapcsolata (1945–1948)’, Századok, (2019), 718–21.

[44] Borbála Klacsmann, ‘Neglected Restitution: The Relations of the Government Commission for Abandoned Property and the Hungarian Jews, 1945–1948’, Hungarian Historical Review, 9.3 (2020), 513–20. In our article we are not dealing with the long-term effects of the confiscations at all, for which see, e.g., Ágnes Peresztegi, ‘Reparation and Compensation in Hungary 1945–2003’, in The Holocaust in Hungary: A European Perspective, ed. by Judit Molnár (Budapest: Balassi Kiadó, 2005), pp. 677–84. Nor do we investigate the fate of valuables (gold, paintings etc.) on the so-called Golden train (Hun. Aranyvonat), which has been extensively analysed by Gábor Kádár and Zoltán Vági: Aranyvonat: Fejezetek a zsido vagyon történetéből [Golden train: Chapters from the History of Jewish Wealth] and Hullarablás. A Magyar zsidók gazdasági megsemmisítése [Robbing the Dead. The Economic Annihilation of Hungarian Jews].

[45] SzJCA 1945/262.

[46] SzJCA 1945/118, 1945/119 and 1945/120.

[47] On how the church failed to efficiently help the local Jews, see Pataricza and Czimbalmos, ‘Post-war narratives of the conversion’.

[48] Délmagyarország, 20 April 1945, p. 3; 31 May 1945, p. 2. Quoted in Frojimovics and Molnár, ‘Szeged – Strasshof – Szeged’, p. 193 and p. 197.

[49] Testimony of György Kármán, USC Shoah Foundation, interview ID: 50645.

[50] One of the most well-known depictions of this phenomenon is the movie “1945” (2017), directed by Ferenc Török), which portrays the shame, guilt, and denial of the locals in a small Hungarian village as they try to confront the truth of their actions in taking and never returning the property of Hungarian Jews during and after the Second World War.

[51] Memoir of Mrs Ferenc Bognár, née Irma Spuller (unpublished manuscript), p. 20.

[52] Pál Lányi, ‘Szegedi gettóládánk kifosztása’ (Budapest, 2022) (unpublished manuscript).

[53] Deportáltakat Gondozó Országos Bizottság, “Jegyzőkönyv 3555” [Testimony of Jenő Ligeti (no. 3555)]. <http://degob.hu/?showjk=3555> [accessed on 29 March 2023]. The same narrative is given by Arnold Kármán (b. 1880, Temesvár) in another DEGOB testimony (no. 3576); all of his property was taken away when he returned.

[54] SzJCA, letter written 24 May 1945, uncatalogued documents from Szeged city, 1945.

[55] See more Ronald W. Zweig, The Gold Train: The Destruction of the Jews and the Looting of Hungary (New York: Morrow, 2002).

[56] Testimony of William Farenci. USC Shoah foundation, interview ID: 18631, segment 28.

[57] e.k., ‘Beszéljünk másról’, Szegedi Népszava, 2 April 1946, p. 4.

[58] Testimony of Ágnes Szigeti, USC Shoah Foundation, interview code 51018, segment 71–72.

[59] SzJCA 1945/429.

[60] The cases of Béla Szabó and Mrs Izsó Szécsi in the SzJCA records from 1945, the documents of Dr Dénes Návai, a lawyer from Szeged. In the latter case, József Várhelyi attempted to pressure the staff of the Szeged Jewish Community to allow him to remain in a property that a Jewish survivor, Izsóné Szécsi, rightfully owned. However, the Jewish Community refused to comply with his demand as they were committed to upholding the property rights of Jewish survivors who had been unjustly deprived of their possessions during the Holocaust.

[61] Város iratai 1945. Április 21.

[62] For children’s accounts of the deportation, see Dóra Pataricza, ‘“The first time I saw my father cry” – Children’s accounts of the deportations from Szeged’, Jewish Culture and History, 24.2: The Usage of Ego-Documents in Jewish Historical Research <doi:10.1080/1462169x.2023.2202085> (under publication).

[63] Vera Gara, Least-Expected Heroes of the Holocaust: Personal Memories (Ottawa: Vera Gara, 2011), pp. 19–20.

[64] Testimony of Edith Molnár. USC Shoah Foundation, interview ID: 22798, segment 35–37.

[65] Auslander ‘Coming home’; Anna Wylegała, ‘The Void Communities: Towards a New Approach to the Early Post-war in Poland and Ukraine’, East European Politics and Societies, 35.2 (2019), 407–36 <https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325420914972>; Waligórska, Sorkina, ‘The Second Life of Jewish Belongings’, p. 2.

[66] Délmagyarország, 26 August 1945, p. 6.

[67] Délmagyarország, 22 February 1945, p. 4.

[68] Béla Seifmann placed the following advertisement in the Délmagyarország newspaper on 1 March 1945: Anyone who has taken clothing or anything of value from widow Mrs József Seifmann or my sister Józsa for safekeeping, please report to Béla Seifmann, Tömörkény u. 8, between 12–2 noon or Lajta u. 6 within five days.

[69] For the Joint’s [short for American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee] activities in Szeged, see Pataricza, Dóra: “‘Please give me back my nightstand lamp’ – The Joint’s activity in Szeged in the aftermath of the Holocaust”, JDC Archives Webinar, Ruth and David Musher Fellowship, 28 April 2021 (online). Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jmgAdeLAOU4&t=320s.

[70] Seifmann Béla visszaemlékezése. Egy munkaszolgálatos naplója, ed. by Dóra Pataricza and András Lénárt (Budapest: HDKE, 2023), pp. 38–39.

[71] Email correspondence between the author and Mrs János Horváth, née Teréz Löw, 19 May 2021.

[72] Szegedi Népszava, 9 June 1945, p. 2.

[73] ‘Besúgók napja a szegedi népbíróságon’, Szegedi Népszava, 22 September 1945, p. 2.