INTRODUCTION

On 24 February 2022, the world woke up to terrible news: Russia had invaded Ukraine. Since then, Ukraine has become the focus of world news and Ukraine was more highly searched in February 2022 than at any point in Google Trends history. With every day of the war, new images of heroes appeared and started to circulate via pop culture channels in Ukraine and abroad. Heroes such as President Volodymyr Zelenskyi and General Valeriy Zaluzhnyi came not only from political elites but also from below, including soldiers, volunteers, ordinary citizens, and children. The need for heroes is especially crucial during military conflicts since it assists in uniting people and bringing hope for the better in the dark times of war. On the other hand, it helps to combat enemies on symbolic and discursive battlefields with representations of humour, resilience, and societal power.

War discourse has already been in the focus of research since 2014; for instance, Kusse analysed patterns of argumentation and aggression in different genres of Russian and Ukrainian texts and images.[1] In the collective monograph Language of Conflict: Discourses of Ukrainian Crisis, the rhetoric of the conflict is highlighted from various angles and perspectives: in parliamentary debates, presidents’ speeches, online media, and TV shows.[2] Moreover, Semotiuk examined the terminological and discursive dimensions of the Russian-Ukrainian military conflict.[3] However, with the full-scale invasion, both political rhetoric and popular beliefs – in other words, top-down and bottom-up cultural movements – are in the process of thoroughgoing transformation and consequently need more attention from researchers.

The opposition between “us” and “them” becomes especially vivid during wartime. Therefore, the Ukrainian people’s resistance stems from national culture (by national culture, we understand elements of art, customs and behaviour that are traditional for a nation) and involves elements of Western global trends, but at the same time it is a response to Russian imperialist ideology and actions.

To highlight the main trends in the popular discourse of the war, we will attempt to answer these research questions:

How is the self-image of Ukrainians constructed during the full-

-scale war?

What elements of national culture (artifacts, persons, traditions) are used in the popular discourse of the war to create new images of heroes?

How does Western globalized culture respond to Russia’s war in Ukraine and how are national and Western elements intertwined in popular discourse?

How does Ukrainian resistance deconstruct the ideology of “russki mir”, and what messages and images in contemporary Ukrainian pop culture stand against the Russian imperialist ideology?

Answering these questions will provide a depiction of the rhetoric of Ukrainian resistance in wartime and will display directions for further research. In this article, we will focus on highlighting the main trends, the most popular memes, songs, images, and other elements of pop culture. Analysing the whole spectrum of contemporary Ukrainian pop culture goes far beyond the scale of this article and needs further research and reflection.

METHODOLOGY OF THE RESEARCH

The linguistics of pop culture is an emerging field that combines sociolinguistics, stylistics, and cultural studies.[4] Moody defines three main features of popular culture: its circulation in mass media, its consumer-oriented nature, and its connection to globalization.[5] Moreover, there are two channels through which language ideologies disseminate via pop culture: performative (language choice) and affiliative (reception and reactions toward language). For researchers, it is important to take both of them into account: “These two channels do not represent competing methods to examine language ideologies in popular culture; language ideologies in any particular instance of pop culture discourse can and should be examined simultaneously in both the performative and affiliative channels”.[6] In this article, we consider both these channels.

Moreover, globalization influences popular culture to a great extent, and analysis of pop culture artifacts could be applied as a tool for a deeper understanding of global trends and movements: “…new technologies and communications are enabling immense and complex flows of people, signs, sounds, and images across multiple borders in multiple directions. If we accept the view of popular culture as a crucial site of identity and desire, it is hard to see how we can proceed with any study of language and globalization without dealing comprehensively with popular culture”.[7] Therefore, globalization and pop culture are tightly interconnected. However, for researchers, it is challenging to analyse artifacts of popular culture since this field is very dynamic – always changing and instantly reacting to social and cultural transformations.

Pop culture is the opposite of both high culture and folklore, but its recent forms interact with both.[8] Pennycook underlines that a very broad range of different creative works is represented under the umbrella of pop culture.[9] Werner described the differing natures of popular culture and pop culture. On the one hand, popular culture is close to folklore, demonstrating grassroots responses from below and spontaneous reactions of people to sociocultural events. On the other hand, pop culture is a top-down commercial product in consumer society.[10] In this article, we analyse both top-down and bottom-up perspectives and the interactions between them.

Furthermore, examining contemporary Ukrainian pop culture, Bilaniuk points out that it represents a crucial area for depicting interactions between different social groups: “A focus on popular culture encompasses institutionally produced and individual forms of expression in which political, artistic, and economic forces intersect, and it is an arena that allows a broad involvement of people from various social strata”.[11] Artifacts of popular culture are mostly written or visual materials[12] but also audial, therefore we use Multimodal Discourse Analysis (MDA) to examine our data (memes, caricatures, songs, graffiti, cartoons, merch) as MDA “extends the study of language per se to the study of language in combination with other resources, such as images, scientific symbolism, gesture, action, music and sound”.[13]

In our research, we applied Multimodal Discourse Analysis (MDA) to examine both linguistic (verbal) and non-linguistic (visual, auditory, etc.) semiotic resources, considering each as equally important in conveying a message.[14] This paper ascertains how visual and visual-audial products of pop culture are intentionally created to express and disseminate ideas, views, beliefs, and identities in mass media and social media. This study will enhance our understanding of how various semiotic resources – such as verbal, visual, auditory, and kinetic – are utilized in popular culture genres to achieve social goals like explanation and persuasion. In this article, we use a qualitative approach since our goal is to highlight the main trends in contemporary war discourse, therefore we refer to the most popular and widespread artifacts of contemporary Ukrainian and Western pop culture in social media. Russia’s war in Ukraine is ongoing, and new memes, songs, poems, films, and posters emerge daily as responses to the trauma experienced by Ukrainian society. Therefore, quantitative research needs more observation and data collection; moreover, there are already researchers who are working on depicting the material of war discourse.[15]

BE BRAVE LIKE UKRAINE – TRADITIONAL ETHNIC ELEMENTS IN THE POP CULTURE RESISTANCE

On 24 February 2022, the very first day of the full-scale war, one of the most powerful memes of the war discourse appeared: Russian warship, go f*ck yourself! This was a reply by the Ukrainian border guard Roman Hrybov to a Russian soldier’s proposal from the cruiser “Moscow” to surrender. The phrase immediately became a meme, a basis for numerous artworks, social media shares, Western newspaper headlines and definitions in Urban Dictionary. Later the Moscow cruiser was sunk after an attack by the Ukrainian army, which caused even more memes and artwork. For instance, the scene twice appeared on the Ukrposhta postage stamp, which became extremely popular and sold out immediately.[16] Concerning language choice, Ukrposhta softened the verbal aggression and shortened the phrase to Russian warship, go… (see ills 1 and 2). Language changes naturally occur when a bottom-up interacts with a top-down perspective, therefore folk artifacts can become part of the official discourse. Reflecting on satire during wartime, Semkiv noticed that with this Ukrainian border guard’s phrase the period of mocking the enemies and black humour started, and it is still ongoing. Moreover, Semkiv concluded that humour assists Ukrainian society in overcoming trauma during wartime.[17]

During the very first months of the full-scale war, new heroes were especially badly needed to overcome the shock of this new traumatic social experience. Ukrainians mostly heroised simple persons: a tractor driver or a Roma who stole Russian tanks, a woman who knocked down a Russian drone with a can of pickled vegetables (see ills 3 and 4), and so on. Therefore, a bottom-up perspective prevailed in war discourse during the first months of the full-scale conflict. These images not only circulated in Ukrainian online and social media but also reached Western audiences. For instance, the following phrase and definition appeared in the popular online Urban dictionary: “Ukrainian Tractor Pull. The act of stealing a main battle tank by towing it behind a standard farm tractor. We can defend our homeland by organizing a Ukrainian Tractor Pull (by NerdyShenanigans, 5 March 2022).

Moreover, in April 2022, a public campaign began that could be considered as a visual branding of the country: Be brave like Ukraine. It underlined the bravery of the Ukrainian people and delivered this message to Ukrainian and Western audiences. The campaign was launched by the creative agency Banda together with the Office of the President of Ukraine, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, the Minister of Culture and Information Policy, and the Ministry of Digital Transformation, therefore it was mostly top-down by its nature. The initiators and developers of the campaign claimed that its main messages and goals are as follows:“

…first of all to maintain fighting spirit of all Ukrainians; secondly, to not let the world to forget what is happening in Ukraine; and thirdly, to associate bravery with Ukrainian people”.[20]

Ill. 3. In the field a tractor says – dyr-dyr-dyr (a line from Ill. 4. Good evening, we are from Ukraine (famous phrase

the Ukrainian poet Pavlo Tychyna’s poem)[21] the author of phrase is Marko Halanevych, leader

of originating from contemporary Ukrainian;

music Dakha Brakha band). The phrase became

very popular and often used by politicians[22]

Thanks to this campaign, whose main slogan was Bravery made in Ukraine, posters with messages about the bravery of Ukrainian people appeared in many European and American cities and in such symbols of global culture, such as Times Square in New York (see ill. 5). Moreover, several Ukrainian fashion brands, such as Braska, Diadia, One by One, keepstyle, Dodo socks, Siyai, Aviatsija Halychyny, Starberry.ua, and Gepur[23] (ill. 6) produced patriotic collections of clothes. Some of these brands’ profits are donated to the Ukrainian Armed Forces. National colours – blue and yellow – were dominant in visual representations of bravery and solidarity. This could be compared with the protest symbols of Euromaidan (2013–2014), when protesters refused to promote political parties’ symbols and mostly used national flags while protesting on the main squares of Ukrainian cities.

The Ukrainian resistance is also transmitted via traditional songs. A video of a 4-year-old boy called Leo singing The Red Viburnum in the Meadow, which was one of the main songs of the Ukrainian Sich archers at the beginning of the twentieth century, subsequently went viral and attracted a million views on YouTube.[26] Leo was displaced with his parents to the Transcarpathia region because his home city of Irpin was occupied and heavily damaged during the very first days of the full-scale invasion. Leo sang a version of the song that was performed in the very first days of the war by the Ukrainian singer Andriy Khlyvniuk, who joined the Ukrainian Armed Forces immediately after Russia’s full-scale invasion. Leo’s performance of the song provoked flash-mobs among Ukrainian kids, who recorded videos of themselves singing this song and posted them on the social media. The words of the song, originally written at the beginning of the twentieth century, contain symbols relevant to the current wartime Ukraine:

In the meadow there a red viburnum bent down low,

For some reason our glorious Ukraine has been worried so.

And we’ll take that red viburnum and we will raise it up,

And we, our glorious Ukraine, shall, hey-hey, cheer up – and rejoice!

Besides, Ukrainian schoolchildren sing the national anthem in shelters, hiding from bomb attacks during school lessons. We could also draw parallels with Euromaidan, when protesters sang the national anthem as a symbol of solidarity almost every hour while standing in frosty weather at Independence Square in Kyiv.

Another resistance song is Stefania, performed by the rap-folk band Kalush Orchestra, winning first place at Eurovision 2022 in Turin, Italy.[27] The name of the song and its verbal and audial components stem from ethnic traditions. Written long before the full-scale invasion as an “ode to mother”, the song has taken on a special meaning during these times of war:

Stefania mum mum Stefania

The field blooms, but she is turning grey

Sing me a lullaby mum

I want to hear your native word.

The song was performed at Eurovision in a modest manner: the members of the band were wearing national vyshyvanka costumes from the Prykarpattya region (the band’s name Kalush is the name of a town in that region). Also elements of Ukrainian mythology and artifacts were used when creating the costumes; for example, traditional prints of Ukrainian Hutsul carpets were applied to create an image of a Kylymman dancer. As regards the language choices, local dialect words were used along with standard Ukrainian language in the text of the song. During the performance, a video of an old crying woman was displayed behind the singers. This combination of audial and visual elements – and to some extent the contrast between the lyrics and war scenes – brought the band success at Eurovision. Moreover, many other participants supported Ukraine, wearing blue-yellow ribbons or flags during their performances. At the end of the performance, Oleg Psiuk made a political statement, asking people to support the Ukrainian cities of Mariupol and Azovstal. Despite the fact that this was against the rules of the Eurovision song contest, the band won. Google searches for the words Mariupol and Azovstal were extremely frequent immediately after the contest, thus showing that the message had reached and influenced the Western audience. The pink hat worn by Oleg Psiuk, the leader of the band, became the prototype for fashionable accessories for kids and adults not only in Ukraine but also abroad. Illustrations 7 and 8 demonstrate how the pink hat image was used for posters by popular Ukrainian artists, such as Grekhov and Inzhyr.

Ill. 7. Stefania mum Stefania![28] Ill. 8. Stefania mum mum Stefania

The field blooms, but she is turning grey

Sing me a lullaby mum

I want to hear your native word[29]

Moreover, Ukrainian mobile operators and banking applications use the image of a pink hat as part of their logotypes. So, we can see how national elements, both visual and audial, are intertwined with Western pop culture and the reactions they elicit among Ukrainian citizens, artists and corporations.

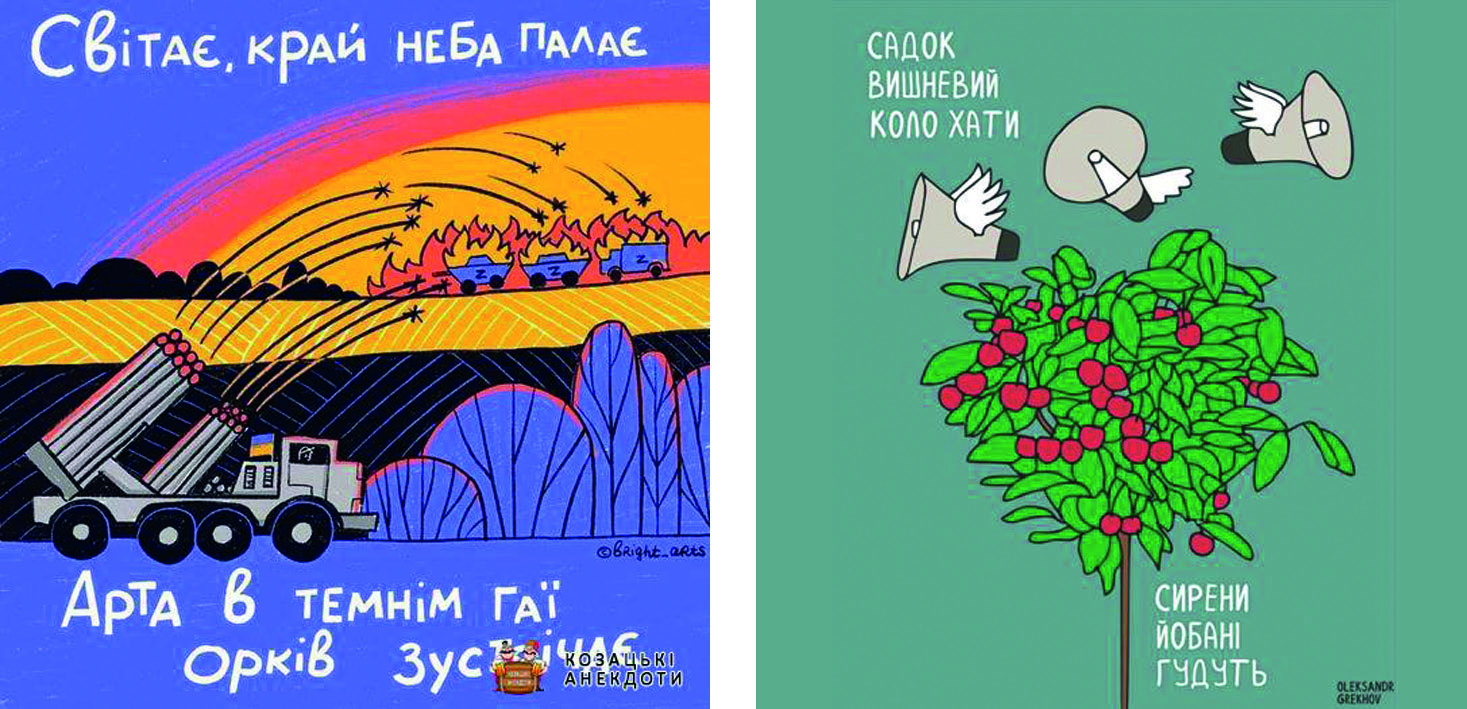

The need for heroes also involved looking in the past, back to the roots of national identity. Therefore, people who had struggled for Ukrainian language, culture, and identity in various periods of entangled Ukrainian history became again revitalized in the field of pop culture, especially with the beginning of the full-scale war. One example is Taras Shevchenko, one of the founders of the standard Ukrainian language and literature. Rostyslav Semkiv explained the popularity of this person during wartime by the fact that he always was a symbol of protest against Russian tsarist imperialism.[30] The image of Taras Shevchenko and citing his poems were also popular at the Maidan events. During the full-scale invasion, a video of Ukrainian soldiers removing a Russian flag with the statement We are one nation and revealing a poem by Taras Shevchenko under it went viral and was shared many times on social media.[31] Moreover, the top-down perspective borrowed from this bottom-up discourse when President Zelenskyi used a fragment of this video in his 2023 New Year speech. Lines from Shevchenko poems are also used by contemporary artists, such as Oleksandr Grekhov and @bright.arts for their ironic war posters (see ills 9 and 10).

Ill. 9. The dawn has come, Ill. 10. A little orchard by the dwelling,

The sky’s edge bursts ablaze;[32] F*cking sirens are wailing[33]

In shady glades the artillery meets orcs32

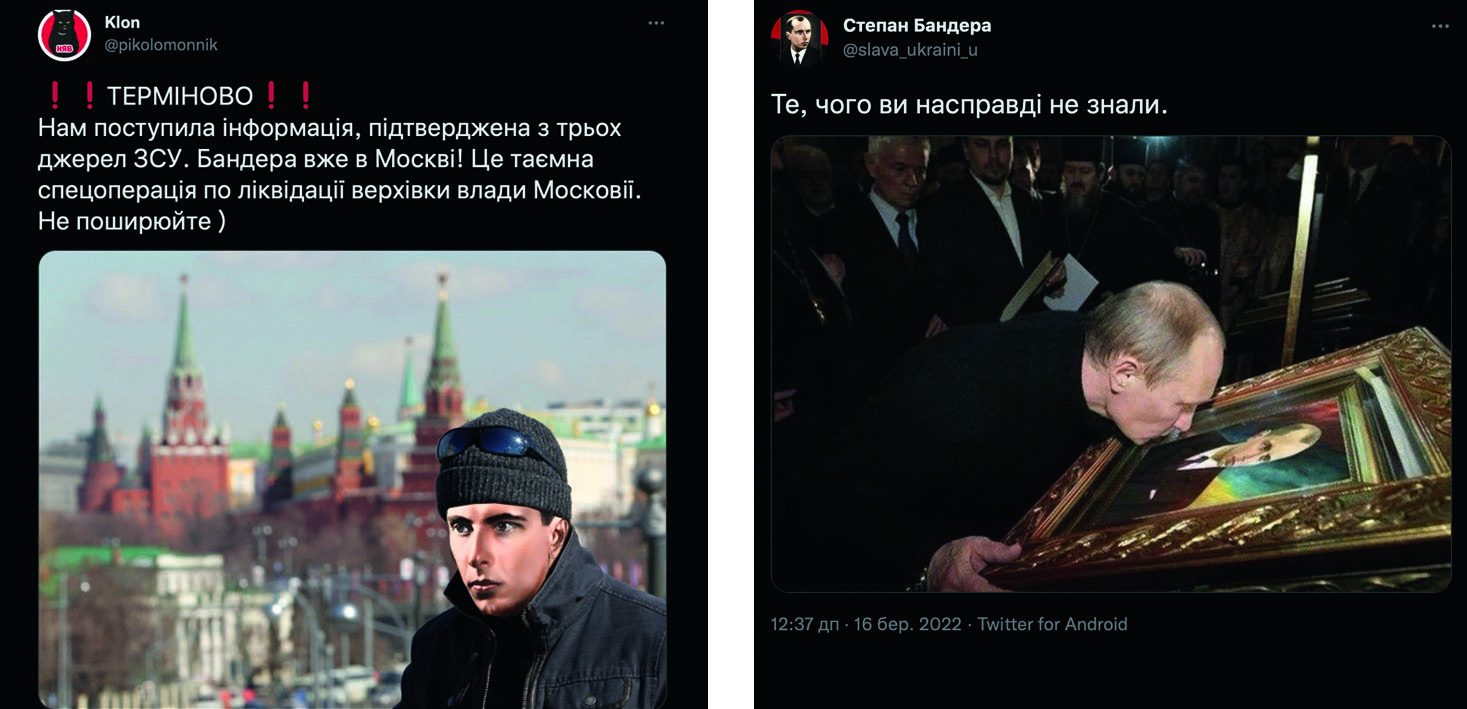

Concerning Taras Shevchenko, he has always been described and perceived positively in Ukrainian society, even during the Soviet times. Hence, people whose activities were described as controversial and triggered international discussions among scholars also appeared in war memes. For instance, a bunch of memes with an image of the historical Figure Stepan Bandera, a leader and organizer of the Ukrainian nationalistic movement, appeared after a statement by Ramsan Kadyrov, Head of the Chechen Republic, that Bandera “is the main enemy of the Russian nation” and that kadyrovtsi (Kadyrov’s army) “very soon will deal with him and later with all other Nazi activities”.[34] In these humoristic memes, Bandera is depicted on Red Square in Moscow with a warning about a special operation on Kremlin leaders (ill. 10) or on a religious icon (ill. 11). In one anecdote it is stated that Bandera is hiding in the Lviv metro to underline the absurdity of Kadyrov’s statement (there is no metro in Lviv and Bandera died back in 1959). The image of Bandera is also mentioned in Ukrainian resistance songs. For instance, Lesia Nikitiuk and Stepan Giga made a remix of Giga’s hit song Cej son (This dream).[35] In the remix, they describe a grotesque situation after the Ukrainian victory, in particular there are the lines in Mausoleum Bandera lays and “Red Viburnum” sounds…

Ill. 11. Urgent! We received information, confirmed[36] Ill. 12. That you actually did not know[37]

by three sources in the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

Bandera is already in Moscow! This is a secret

special operation to liquidate top authorities

of Muscovy. Do not share36

Bandera’s popularity in popular culture could be also explained by an increase in positive attitudes to this historical figure, especially during the full-scale war. According to sociological group Rating, this change in the positive perception of Bandera is tremendous: from 22% in 2012 to 74% in 2022.[38] Different variations of the song Batko nash Bandera, Ukrajina maty (Our father is Bandera, Ukraine is our mother), based on a folk song Oj u lisi, lisi zelenomu, also belong to the popular culture of resistance. The song appeared in 2019 and later became popular on social media. In 2021, a flashmob started after teenagers from Lviv uploaded a short video with this song on TikTok. The flashmob was joined by students, teenagers, famous singers such as Andriy Khlyvniuk and Verka Sierdiuchka, and even national deputies.[39] Therefore, images of different historical figures are used as a part of the Ukrainian resistance. In this article we demonstrate this trend using the examples of Taras Shevchenko and Stepan Bandera, but the whole spectrum of the historic personalities needs further research.

WHAT IS YOUR SUPERPOWER? I AM UKRAINIAN – ELEMENTS OF WESTERN POP CULTURE IN THE WAR DISCOURSE

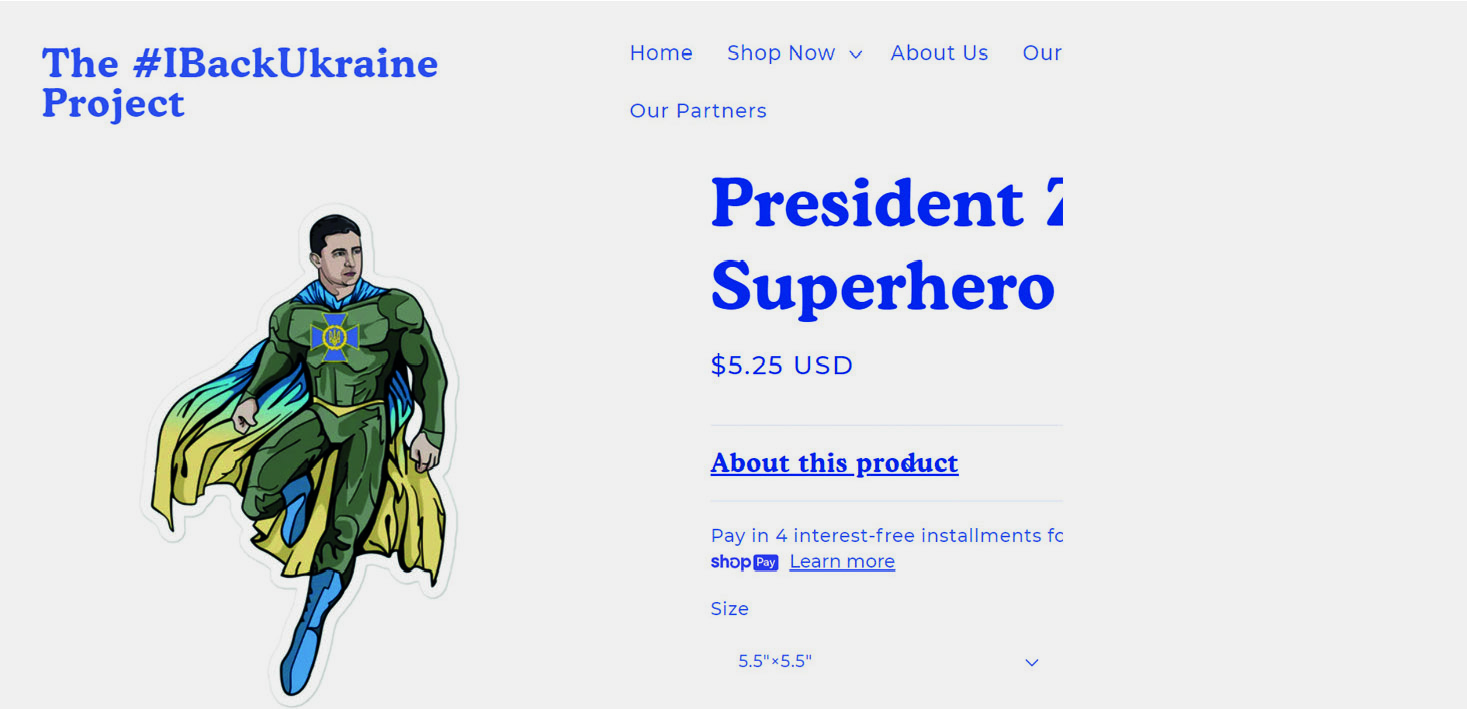

It is possible to assume that the need for superheroes is an eternal infantile attraction to the elder, which remains with us regardless of experience due to the subjection of human nature to fate. From this point of view, reliance on superpowers is actually an escape from deep powerlessness. It is noteworthy that during the global exhaustion of recent years, a country that has been unfairly little visible during history has appeared to be that exact ‘elder’ for the same world. An adult who you can admire, who you can rely on, and, let us be frank, an adult whose problems you don’t care too much about, but who you know is strong, intelligent, and will somehow pull through. And since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, we have observed an interesting phenomenon in Western pop culture: the maturity and mastery with which Ukrainians resist the Russian onslaught is literally turning Ukraine into a new superhero. Slogans like What is your superpower? I am Ukrainian and Be brave like Ukraine, so widespread in mass culture, testify to the recognition of Ukraine at least as a world idol. This trend is noticeable in many areas – from thoughtless merch to works of art.

After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russian military troops, pro-Ukrainian merch has become a significant element of Western culture. Patriotic goods with various slogans about Ukraine and Ukrainians, blue and yellow colours of clothes, accessories, stationery, books, toys, and even food products testify to the support for the Ukrainian nation, but on the other hand these are just following the global trend. Patriotic goods with various slogans about Ukraine and Ukrainians have flooded stores worldwide. Clothes, accessories, stationery, books, toys, and even food products – everyone is now trying to wear blue and yellow tones or verbally testify support for the superhero of the current year. Currently, Amazon, AliExpress, and many other retailers offer this type of product (see ills 13–16).

Ill. 13[40]

Ill. 14[41]

Ill. 15[42]

Ill. 16[43]

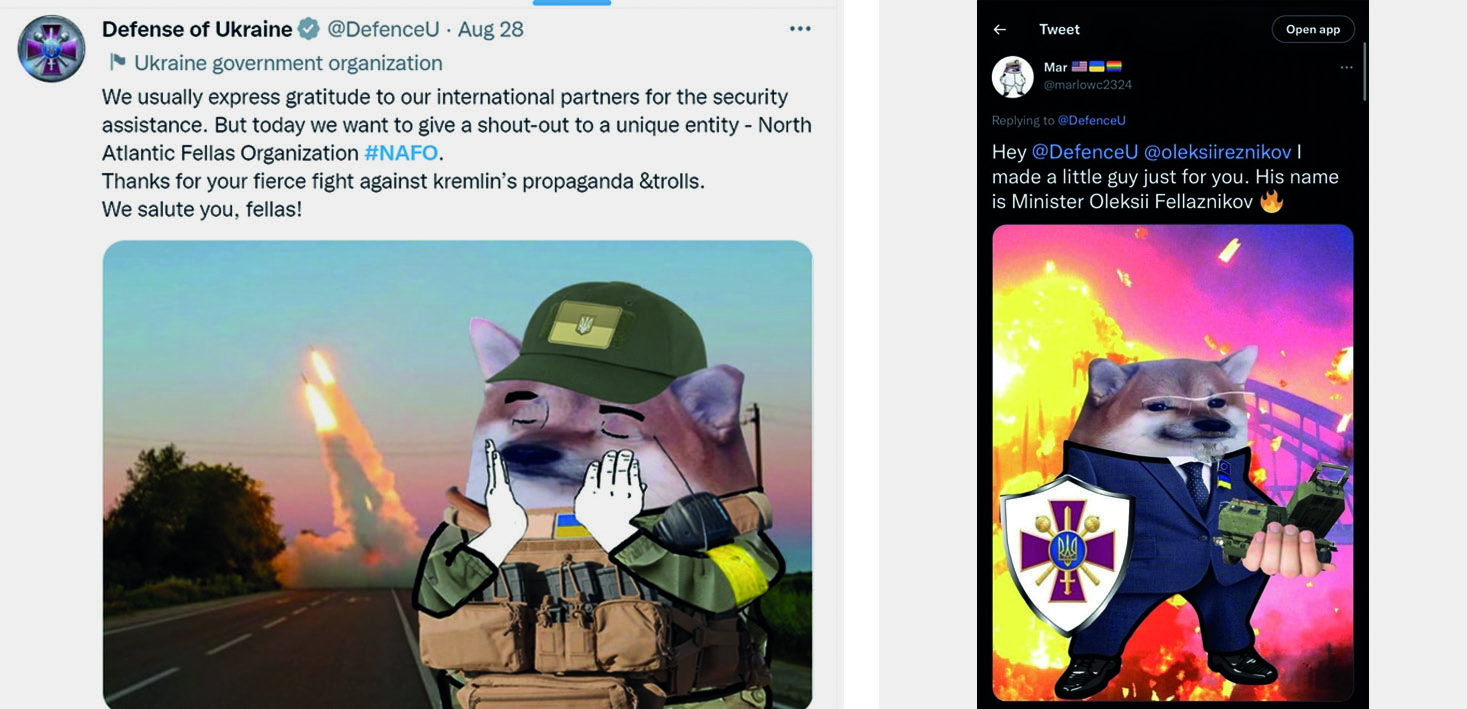

In the context of the war in Ukraine, memes as a special modern type of reflection in the public information space reached their apogee in the image of NAFO. The North Atlantic Fellas Organization is a wordplay on NATO that can be considered sarcastic and ironic at the same time. NAFO itself is a social media movement dedicated to countering Russian propaganda and disinformation about the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. The main visual symbol of this phenomenon is the Shiba Inu dog, which has been known for many years as the most meme-like breed on the internet (see ill. 17). Additionally, in the months since the invasion, many war-related meme channels have sprung up online, such as Saint Javelin, Ukrainian Memes Forces.

Ill. 17[44]

Users involved in the NAFO community, the so-called fellas, actively troll Russian politicians and propagandists and also organize fundraising campaigns to help Ukraine. The movement has gained such scale that it has even been recognized by the Ukrainian authorities on Twitter. In August 2022, the official account of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine published its thanks and respect to NAFO with a humorous military image of a Fella (see ill. 18). Furthermore, a few days later, high-ranking military and civil officials in Ukraine and NATO countries, including the Minister of Defence of Ukraine, Oleksii Reznikov, changed their Twitter avatars to a Fella. It should be mentioned the Minister’s avatar was created by the community and commissioned in his honour (see ill. 19).

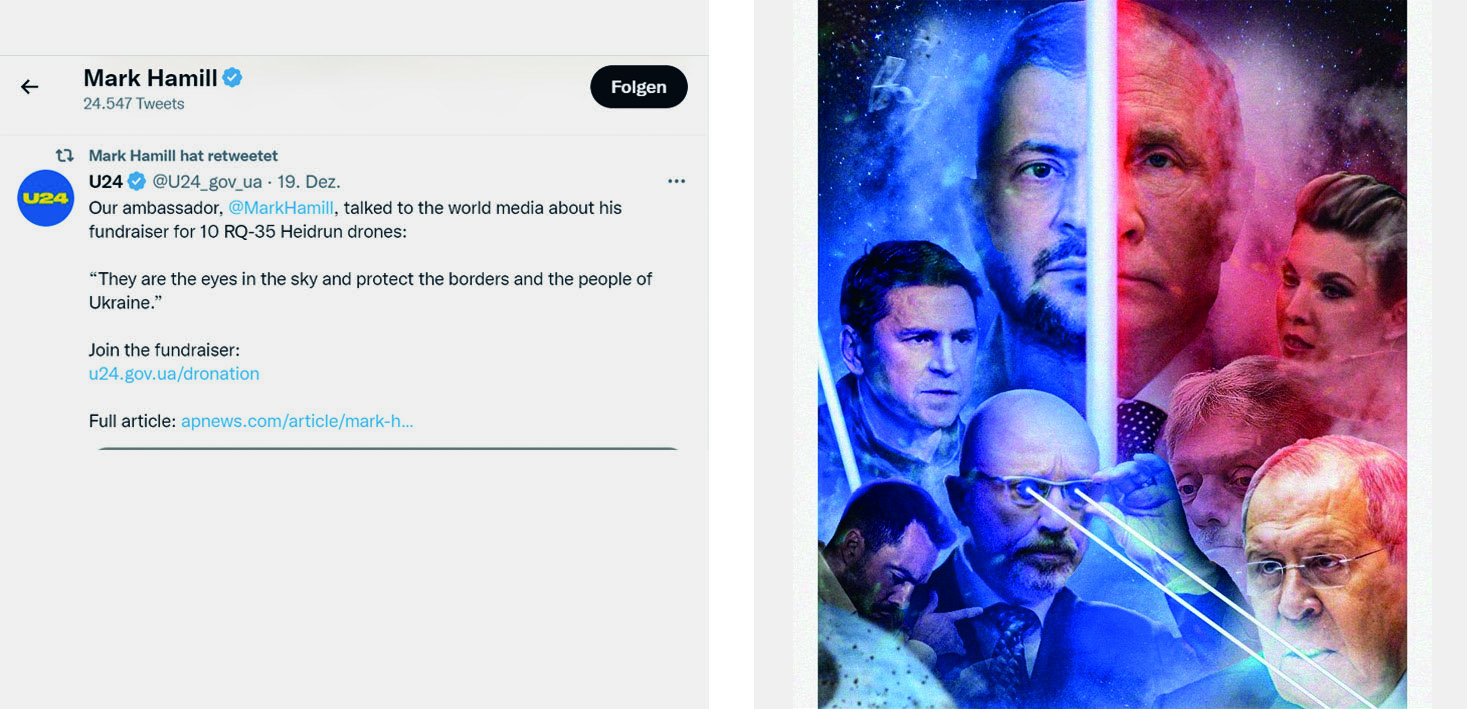

One of the most powerful references in pop culture is the noble gesture of ‘Star Wars’ actor Mark Hamill, better known by the name of his character Luke Skywalker. He has been leading Nowadays, a campaign to gather an army of 500 drones for the war. No doubt, his popularity has contributed to the success of this campaign (see ill. 20).

Ill. 20 @U24_gov_ua: Our ambassador, @MarkHamill, Ill. 21 @Gerashchenko_en:

talked to the world media about his fundraiser May the 4th be with Ukraine Poster is dedicated to

for 10 RQ-35 Heidrun drones: “They are the eyes the International Star Wars Day on the 4th of May

in the sky and protect the borders and the people[47] #StandWithUkraine[48]

of Ukraine”47

Also, world famous singers, especially pop or rock stars, have recently shown a deep interest in collaborating with Ukrainian artists or introducing Ukrainian motifs into their own work. In the spring of 2022, the chart-topping English singer Ed Sheeran re-released the famous track 2step in collaboration with the band Antytila, whose members have been fighting as members of the Ukrainian resistance. A new section of the song is written in the Ukrainian language and conveys the message of loved ones holding on to hope during separation in wartime. In addition, some parts of video for this version were filmed in and around Kyiv in places recently destroyed or damaged by Russian missiles. Another notable collaboration was the release of Kalush (Ukraine) and The Rasmus (Finland). The outstanding track In The Shadows of Ukraine is a remastered version of The Rasmus’ hit.

One of the most unexpected releases and an undeniable hit in the first months of the full-scale war was the collaboration of the legendary band Pink Floyd with Ukrainian singer and defender Andriy Khlyvnyuk. The release description on Pink Floyd’s official YouTube account reads, “Hey, Hey Rise Up’, released in support of the people of Ukraine […] This is the first new original music that they have recorded together as a band since 1994 The Division Bell. The track uses Andriy’s vocals taken from his Instagram post of him in Kyiv’s Sofiyska Square singing ‘The Red Viburnum In The Meadow’, a rousing Ukrainian protest song written during the first world war. The title of the Pink Floyd track is taken from the last line of the song, which translates as ‘Hey, hey, rise up and rejoice”. Other iconic songs ‘Harry’[49] and ‘Warriors of Light’[50] by Lyapis Trubetskoy, well-known since the Revolution of Dignity, were also performed in Ukrainian in 2022. The lyrics were translated by prominent Ukrainian poet, musician, and volunteer Serhiy Zhadan. Both music videos were presented on the official YouTube channels of the band. It is worth adding that the Belarusian bandLyapis Trubetskoy and, in particular, its frontman Serhiy Mikhalok have been supporting the Ukrainian resistance since the Revolution of Dignity. They have been living in Ukraine since 2015, and since the invasion they have been touring Europe raising money for volunteer purposes.

In 2018, UKRMAN, the first modern Ukrainian superhero in the world of comics, was introduced – the first project of its kind in Ukraine. At that time, the authors of UKRMAN wanted to create a hero with whom every Ukrainian could associate himself in the context of the centuries-old history of nation-building. From the perspective of 2022, it seems that UKRMAN is each of us, at least that’s what we and many people around the world want to be. At the same time, one can simply say, ‘I am Ukrainian’, or, to be more precise, ‘I am UKRWOMAN’. Thanks to Ukrainians – the general public, the army, volunteers, activists, and politicians – a superhero epic is being created before our eyes. For example, one inspiring legend from the first months of the invasion soon became the basis for a manga by Japanese author Matsuda Juko, an author who specializes in military comics. This manga is about the so-called ‘ghost of Kyiv’, who allegedly brought down roughly 40 Russian planes during the invasion. In fact, a whole team of professional pilots was behind this. However, the beautiful legend inspired a whole comic book which was immediately was translated and published in Ukraine after its release in Japan. The conflict in the comic book starts with an episode where the Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu disgruntledly informs the command about the failure of the offensive operation and the complete frustration of the Russian troops due to the unexpectedly powerful air defence of Kyiv. Also, one of the dialogues emphasizes that Russia was not ready for such support for Ukraine from the West.

Also, on 27 November 2022, the Bleeding Cool website reported that DC Comics’ superhero team Stormguard (an imaginary organization of superheroes that seeks to protect the Earth from alien threats) would be joined by Core hero Pavlo Stupka, a new Ukrainian character. Actually, such glorification of Ukrainian soldiers began long before the full-scale Russian invasion. Ukrainian society began to metaphorize the defenders as superhumans from the very beginning of the war. Thus, in 2014, the participants of Donetsk airport defence (all of them volunteers) began to be called cyborgs, which literally means a fantastic creature, half-man and half-machine, with mechanical and electronic components that replace its organs and body parts. Today, not only Ukrainian warriors but also civilians who demonstrate resilience and perseverance in the fight against the enemy are rightly considered to have superpowers.

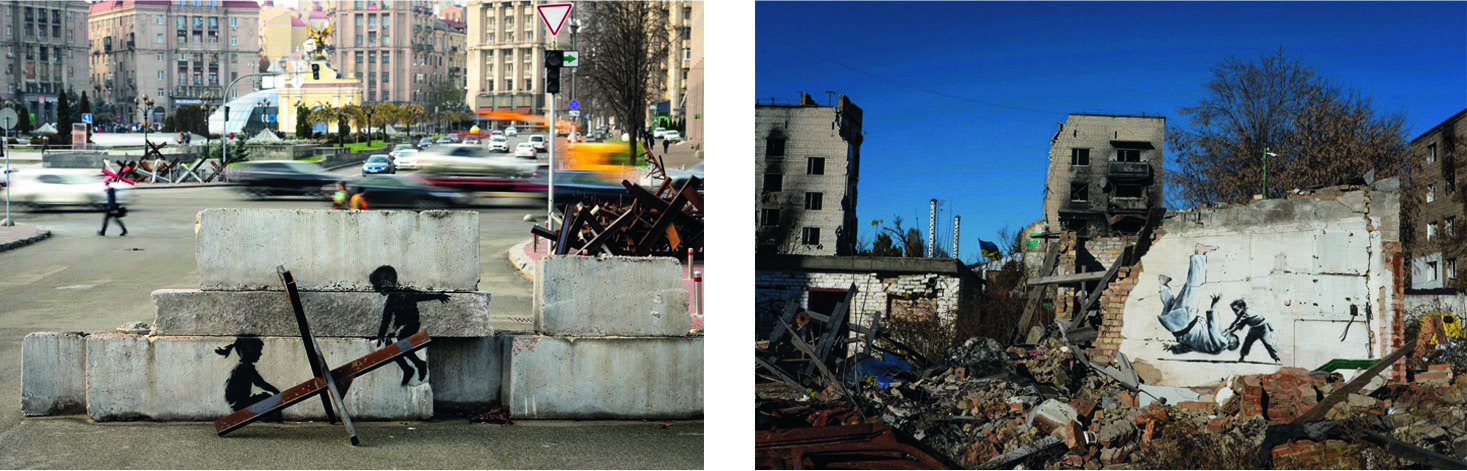

Another manifestation of Western pop culture is street art. Many war-themed murals have appeared in such different European capitals as Vienna, London, Berlin, Paris, and Warsaw. In November 2022, the English artist Banksy, whose graffiti is known all over the world, produced works in Ukrainian settlements in the Kyiv region, directly on the walls of buildings that had been subjected to rocket attacks. Banksy brought his signature art into the war environment, and then his artworks immediately integrated into this environment, which instantly recognized them as its own and as a means of strengthening its own discursive position. This is predictable as the social context always dictates the places for Banksy’s new works. At the same time, this kind of global recognition constitutes an unconditional added value to the murals. Banksy’s first artwork on the ruins of a flat building destroyed by a Russian missile depicts an old man serenely washing in the bathroom and rubbing his back with a large brush (see ill. 23). Black and white paints, usual for Banksy, give a special semantic load to this picture as they depict the measured everyday life of Ukrainians ‘before’. Another of Banksy’s works also appeals to the military routine of Ukrainian civilians. A woman is dressed in bath clothes and a gas mask, holding a fire extinguisher. Literally, this is the next stage of getting used to war: acceptance, but also constant readiness to defend oneself (see ill. 24).

It is noteworthy that the next piece of graffiti depicts children. If you look at it from the point of view of the eternal infantile attraction to the elder which was discussed above, it can be interpreted as a recognition of the incredible strength of those who are considered weak, i.e., us, Ukrainians. We are not looking for an ‘elder’ – we act like adults. Children playing on anti-tank hedgehogs in the centre of Kyiv is our new ‘carefree’ reality, aptly captured by Banksy (see ill. 25).

The final in the series of Ukrainian works by this artist was graffiti of a duel between a little boy and Putin, where the latter is obviously defeated. A very transparent and eloquent allusion (see ill. 26).

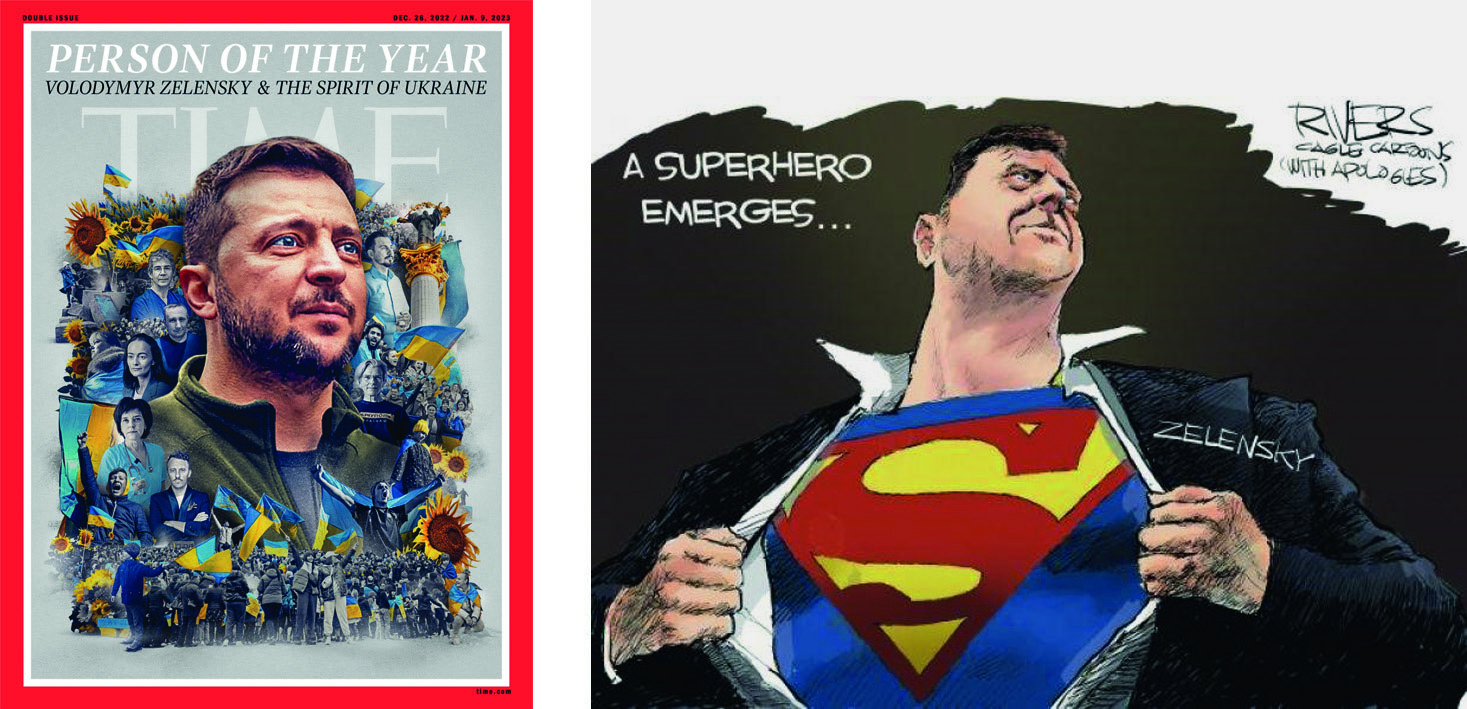

Just like in fairy tales and various fantastic stories, recently in Ukraine an actor-comedian suddenly became a superhero for the world. It is worth noting that such a perception and depiction of President Zelensky is more typical of the Western world than of Ukraine. In December 2022, Time magazine even named him and the spirit of Ukraine the Person of the Year 2022.

On the internet you can find countless piece of fan art, posters, and other creativity about Zelensky in the image of a superhero (see ills 27–28). We might dare to assume that such popularity among the people plays a role not only in Mr Zelensky’s firm state position during the war but also in the absolute absence of a political past, which in a certain way distances him from typical political elites and brings him closer to the people. Moreover, his superhero image refers to him more as a military figure, defender of the nation, than as just a politician.

It is also worth mentioning General Valeriy Zaluzhnyi, who has earned international recognition as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. He quickly became quite a public Figure who constantly communicates with the people and gives interviews to the world media. He also became the face on the October 2022 cover of Time magazine and is included in Time’s 100 most influential people of 2022. Politico magazine in turn called him the ‘iron general’ who is a hero but not a star (see ills 29–30). Not only Ukraine’s military leaders have been heroized, but also Western politicians who support Ukraine. For instance, Boris Johnson, a British politician who is well-known for his consistent support of Ukraine, coined the phrase Dobryi den everybody, which became a meme and is often used on memes and merch.

.jpg)

Beyond all the above examples, and perhaps above all, in the context of pop culture in times of war, it is worth mentioning the euphemisms that Ukrainians use to call the enemy. Ukrainians mean Russians when they say ‘orcs’, and they mean Russia when they say ‘Mordor’. These names, as it is well known, are taken directly from Western culture, the cult of the epic Lord of the Rings. This opens up another perspective of the image of Volodymyr Zelenskyy: a young adult who is supposed to save the world. It is valuable that such images, meanings, metaphors, and fantasies are produced in both Western and Ukrainian communities very explicitly. This probably shows that pop culture is an excellent tool for reflection and therapy at all times, especially in times of war.

THE “RUSSIAN WORLD” AS A QUASI-IDEOLOGY OF THE RESTORATION OF “IMPERIAL GREATNESS”

The concept of “russkii mir” or “Russian world”[59] was at first conceptualized by the quasi-philosophical doctrine of Petro Shchedrovytskyi, since when it has laid the ideological foundations of a new neo-imperial geopolitical doctrine. The main components of the “Russian World” are the Russian language and culture, Orthodox faith, common historical past, and common memory. According to Laruelle, “the concept of the “Russian World” is a geopolitical imagining, “a fuzzy mental atlas […] on which different regions of the world and their different links to Russia can be articulated fluidly. This blurriness is structural to the concept and allows it to be reinterpreted within multiple contexts”.[60]

The myth of three fraternal peoples – Ukrainian, Belarussian, and Russian – as the “unity of all-Russian people” is key to the “russkii mir” ideology. The aforementioned trinity is clearly stated in the official documents and speeches of the main actors: Vladimir Putin, Patriarch Kirill, Dmitrij Peskov, Dmitrij Medvedev, and many others. Russian state mythology claims that these three nations are united not just by territory but also by history, culture, and spirit, creating a unique civilization. A Russian historian, one of the founders of the “Russian world” concept, Valerij Tishkov, emphasizes that the “Russian language, as well as Russian-speaking Russian or Soviet culture together with historical memory, unite and construct this world”.[61] The concept of the “Russian world” is an attempt to create a utopian Russian-centric East Slavic “civilizational field” as an alternative to Europe. The ideology of the Russian civilization’s uniqueness is reflected in the National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation (further referred to as the Strategy) and the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation “On Approval of the Concept of the Humanitarian Policy of the Russian Federation Abroad” (further referred to as the Concept). The Strategy highlights the protection of Russia’s traditional spiritual, moral, cultural, and historical memory. Furthermore, the Strategy underlines the destructive effects of the globalization of culture and technology on traditional culture and values. The United States and its partners, multinational corporations, foreign nonprofits, and non-governmental, extremist, and terrorist organizations are directly accused of attacking Russia’s traditional spiritual, moral, and cultural-historical values.[62] In the Concept, the Russian Federation goes further and outlines ways of transmitting the “Russian world” globally. The national interests of the Russian Federation in the humanitarian sphere abroad are seen in the “protection of traditional Russian spiritual and moral values” (13.1), “protection, preservation, and promotion of traditions and ideals inherent in the Russian world” (15.2), and “strengthening the role, importance, and competitiveness of the Russian language in the modern world” (15.4).[63]

As the second pillar of the “Russian World” doctrine, the Russian Orthodox Church has become one of the most significant institutes for preserving the unity of the “Russian World” civilization. On 4 November 2022, Patriarch Kirill in his propaganda speech ‘About the revival of the lost internal integrity of our Fatherland’ repeated like a mantra his artificial ideological clichés about the “single historical space of Holy Rus” and once again quoted his favourite slogan “Ukraine, Russia, Belarus – together we are Holy Rus”.[64] Polegkyi and Bushuyev argue that Patriarch Kirill has begun “to pose not just as the head of the Orthodox Church of Russia but as a supranational spiritual leader of ‘Holy Rus’, which purports to include Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, and – on a broader scale – all Orthodox Christians. From this perspective, Moscow views itself as the ‘Third Rome’ and the only legal inheritor of the Byzantine Empire – in contrast to the ‘false Rome’ of Washington”.[65] Moreover, the Russian Orthodox Church has become “the moral foundation for the Russo-Ukrainian war”[66] and Patriarch Kirill has praised the Russian occupiers for “defending the Russian world”: “Today, Donbas is the front line of defence of the Russian world. And the Russian world is not only Russia but is anywhere where people live and have been brought up in the traditions of Orthodoxy and Russian morality”.[67] Since 2014, the “Russian world” ideology has turned into a justification for direct military aggression against Ukraine “to protect the Russian and Russian-speaking population” and the genocidal policy of the Russian Federation against Ukraine in the ongoing full-scale war. The awareness that the “Russian world” brings death, tears, and devastation encourages Ukrainians to distance themselves from this ideology by any means. The deconstruction of the “Russian world” also occurs in modern pop culture, particularly in songs, memes, caricatures, and anecdotes. In this research, the words “deconstruction” and “to deconstruct” are used in a much general meaning: deconstruction as synonymous with the destruction of an idea or a truth claim, and to deconstruct as synonymous with “to dismantle”, e.g., to show that a claim, statement or explanation is not true or correct since the “Russian world” is “a quasi-ideology that contains exclusively declarative elements of supremacy, without philosophy or rationalization”.[68]

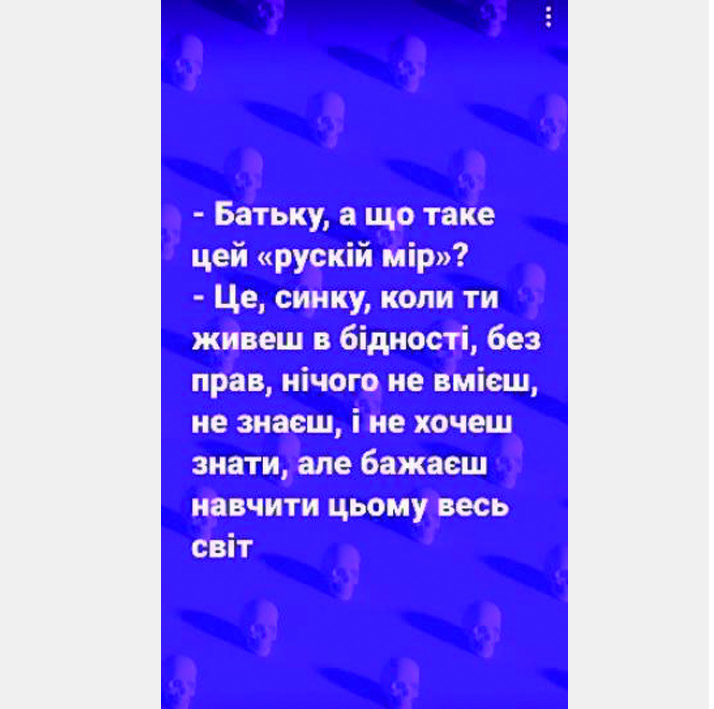

In Ukrainian discourse, the concept of “russkii mir” itself is ridiculed. For example, the anecdote below gained popularity in social media. Its humour makes it possible to reduce Russia’s pseudo-greatness and emphasize the negative features of Russian society. In this fragment, Russia’s desire to transmit its imperialist ideology globally is also treated with contempt.

Ill. 31 – Dad, what is that “russkii mir”?

– That is, son, when ones live in poverty, has no rights,

cannot do anything and knows nothing, and doesn’t want

to know anything but wants to teach the whole world[69]

“NE SESTRY”: HOW UKRAINIAN POP CULTURE DISMANTLES IMPERIAL MYTH OF “FRATERNAL PEOPLES”

In mass culture, Ukrainians’ first attempts to distance themselves from Russian imperial ideology appeared in 2014, immediately after the occupation of Crimea. In March 2014, Ukrainian poet Anastasiia Dmytruk wrote the poem We will never be brothers![70] as a reaction to the Russian annexation of Crimea. The poem had significant resonance and gained more than 3 million views on YouTube. To support Ukraine, Lithuanian musicians, together with the choir of the Klaipėda Music Theatre, created a song based on this poem which had considerable success on YouTube and reached 22 million views.[71] The aforementioned poem starts with the following words:

We will never be brothers!

Neither by country nor by mother.

You don’t have the spirit to be free,

So we can’t even become stepbrothers with you.

You called yourself “elder” –

we could be younger, but not yours […]

You have the Tsar, we have Democracy.

We will never be brothers.[72]

Later, in August 2014, Vadym Dubovskyi, the so-called “singing truck driver”, performed the song “Farewell March”, in which he also tried to deconstruct the myths about “brotherhood between nations”, starting with similar words:

We have never been brothers.

The virus of slavery has entered your souls.

You always showered curses

on Our faith, freedom, and language.[73]

The deconstruction of the “Russian world” and the debunking of the myth about the kinship of peoples are based on categorical oppositions: freedom – slavery, tsar – democracy, etc. In these poems, different values and ideological differences have become a key marker for distinguishing peoples which Russian propaganda stubbornly calls “fraternal”, or even “one nation”. Moreover, Anastasiia Dmytruk points out that the Russian nation proclaims itself “elder” brother – you called yourself “elder”. The fact that the Russians have proclaimed themselves as “bigger and elder” is also mentioned in the song Not brothers but executionersby Amelika Ocean.[74] Since the full-scale invasion, it has no longer been possible to see the statement about “brotherhood” as anything but illegal and false. The war crimes of the Russian army in Bucha, Irpin, Izium, Kherson, and other cities give reason to call them executioners and to draw an even thicker line of distinction between peoples.

The others have come,

They say that they are bigger,

They say that they are elder,

And they pulled the trigger.

They cut off, took away.

[…]

Your heart is a stone

Not brothers, but executioners

And executioners![75]

Masenko contends that the “cradle of three fraternal peoples” is on the verge of becoming a coffin due to one of the “fraternal peoples”; like a kleptoparasitic bird, they are doing everything to throw the true owners out of the nest and replace them. In addition, the image of a “common cradle” is a failed concept since no sane person would put as many as three children in one cradle: these children should be triplets.[76] However, according to the official ideology, the Russian brother – who, together with his two younger brothers, found himself, for some reason, in the same cradle – was proclaimed the eldest. Vadym Dubovskyi underlines that Russia never accepted or recognised the Ukrainian “faith, freedom, and language”,[77] emphasizing Moscow’s imperial ambitions. By distorting its language and spreading false and manipulative notions about Ukraine’s history and culture, the Kremlin attempts to justify its full-scale and brutal invasion of Ukraine.

There are attempts to legitimize the war against Ukraine in the so-called “LPR” (Luhansk Public Republic), which is run by terrorist groups controlled by Russia. In May 2022, “LPR” released the cartoon The Three Sisters about a quarrel between siblings, based on Russia’s propaganda narratives. Allegedly, the reason for this quarrel was foreign suitors – NATO and the EU – which “began to rule the roost in Ukraine and demanded that she bring her sister to serve them”.[78] According to the “creators” of TheThree Sisters, “Russia went to save the sister”. The fact that the Russian Federation itself unleashed a bloody war against Ukraine was not mentioned in the cartoon. In this way, Russian propaganda aims to influence children by providing them with false information and appealing to their emotions.

The song Ne sestry (Not Sisters) by Jerry Heil & Liudmyla Shemajeva[79] has become a kind of response to the propagandistic statements about the “sisterhood of nations”. “Russians often throw out the idea that we are brothers and sisters, but it is obvious that next of kin do not behave like that”, says Jerry Heil in an interview. This music video is an example of combining different modalities (audio, verbal, visual) to convey an idea. The video was based on the cartoon “Nedokolysana” (Eng. Uncradled) (1989) and supplemented with a number of other videos from de-occupied territories to demonstrate how people meet the Ukrainian Armed Forces and rejoice at liberation from the “Russian world”. As for the arrangement, the motive of the song Oi na dubovi ta i hilky vjutsia (On the oak tree, the branches are curling) has been used to make it sound folkloric.

At the very beginning of the song, the authors distance themselves from “family ties” with Russia and note that these “girls” were not siblings but stepsisters who were forced to live in the same house:

Two little girls lived in the room,

Stepsisters in the same house.[80]

Ideological differences, basic moral and ethical values, and the ability to love have become key factors for dividing Ukrainian and Russian peoples in modern Ukrainian poems and songs:

How can you be called a sister

one who never knew how to love?

The one who never knew how to love

neither strangers nor relatives; neither alive nor murdered?[81]

The song Not Sisters is based on oppositions of good and bad, hardworking and lazy, sincere and envious, beautiful and indecorous, etc., giving the possibility not only to indicate the absence of “blood” ties or kinship between Ukrainians and Russians but also to make it possible to outline the line between “us” and “them”. The dichotomy of “self ” and “other” is considered a crucial element that ascertains the structure and mentality of a particular group and outlines its moral and ethical boundaries. Furthermore, identity construction during war differs significantly from peacetime identities: “A dichotomous, zero-sum way of constructing a boundary between ‘me’ / ‘us’ and ‘them’ is, indeed characteristic of situations of extreme conflict and war in which the individual’s fate is perceived, at least by hegemonic discourses of identity, to be closely bound with their membership of a particular collectivity”.[82]

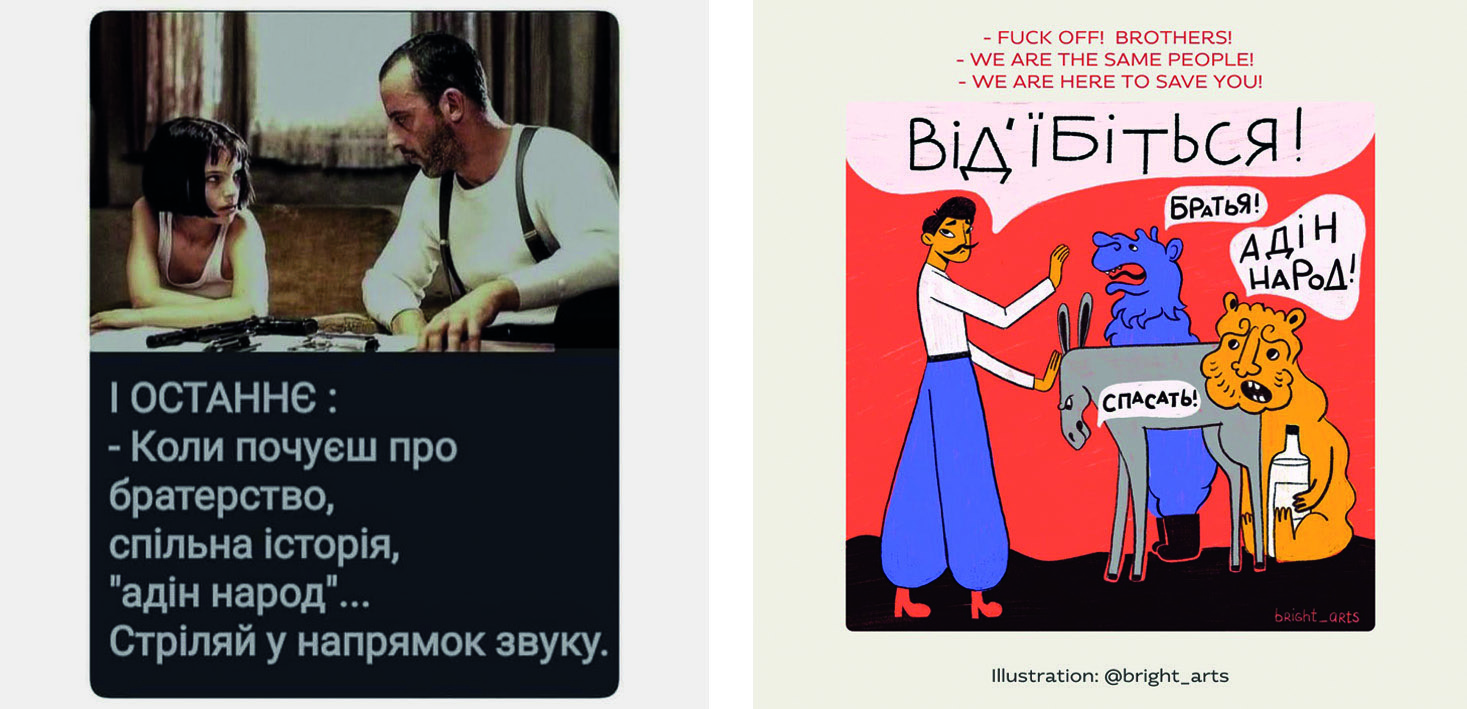

While in songs and poems authors try to demonstrate existential differences between peoples to debunk the myth of “brotherly nations”, in memes there is no further explanation. Ill. 32 clearly shows that anyone with an imperial mindset is the enemy. Meanwhile, ill. 33 illustrates the desire of Ukrainians to keep their distance from Russian manipulative narratives.

Ill. 32. And one last thing… Once you hear something about Ill. 33. Animals:

“two brotherly peoples” and “our common history” – Brothers!

– just shoot toward the sound[83] – One nation!

– To save!

Cossack:

– F*ck off!

Bright Arts[84]

THE UKRAINIAN LANGUAGE AGAINST THE BULLETS: HOW UKRAINE BREAKS “VIELIKII I MOHUCHII”

The Russian language and Russian culture are key elements in constructing and transmitting “russkii mir”. To continue instilling this ideology in Ukraine and allegedly “protect the Russian-speaking population”, Russia “intervened” in Donbas in 2014 and subsequently started the full-scale invasion in February 2022. Ill. 34 illustrates that the “Russian world” ideology brings death and devastation, and behind “angelic” promises of protection and salvation hides cynicism and cruelty (ill. 35). These caricatures are made in a satirical and allegorical style since the image and the text do not correlate. The appeal “Speak Russian! We will come and protect you!!!” must be read as “Do not speak Russian if you do not want the Russian army ‘to protect you’”.

Political caricature by Oleksii Kustovskyi Political caricature by Oleksiy Kustovskyi

Ill. 34. Left: Speak Russian! We will come and protect you!!! Ill. 35. Top: Speak Russian! We will come and protect you!!!

Right: We were forced to protect the Russian-speaking[85] Bottom: Russian world[86]

population in the Donbas region.

Bottom: Russian world85

Political caricature by Oleksii Kustovskyi Political caricature by Oleksiy Kustovskyi

Ill. 36. Language is a weapon. Ill. 37. Our language is our weapon.

The last bridge[87] Palianytsia [loaf][88]

Since February 2022, language has started being perceived as a weapon in the destruction of the “Russian world”, and this is also reflected in memes and caricatures (ills 36, 37). Moreover, language has also become a means of distinguishing between friends and enemies. For example, to refer to saboteurs Ukrainian militants use the code word “palianytsia”, which Russian-speaking people cannot pronounce due to the peculiarities of articulation (ill. 37). This fact has given impetus to create countless memes and jokes demonstrating the differences between the languages.[89] The code word “palianytsia” is also mentioned in the book “One hundred maps about Ukraine and the war” (2022), which has been recently published in Ukrainian, German, and English by the German publishing house “Catapult”.[90]

Some of these memes call to respect the language and switch to Ukrainian since contempt for the Ukrainian language is a manifestation of collaboration (ill. 38) as well as a gesture of support for the occupiers (ill. 39). As Kulyk underlines, “to protest, people no longer use Ukrainian only where it is required by law, but also where they have a free choice. Until now, this choice mostly fell to the Russian language, but now Russian is rejected as the language of the enemy”.[91] Moreover, the letter “Ї” (ill. 39) has become a tool of resistance and a symbol of self-affirmation since it distinguishes the Ukrainian alphabet from the Russian one. The letter “Ї” is drawn on fences and sidewalks, on monuments and the walls of buildings in the temporarily occupied territories.[92]As the Ukrainian writer Dmytro Kapranov emphasizes, “this is a letter that within its appearance loudly declares its Ukrainianness. That is why it has become such a symbol”.[93]

Drawing by the artist Oleksii Kustovskyi

Ill. 38. Disrespect for the official language is a manifestation Ill. 39 Top: Do not support the occupier:

of collaboration[94] Bottom: Speak Ukrainian![95]

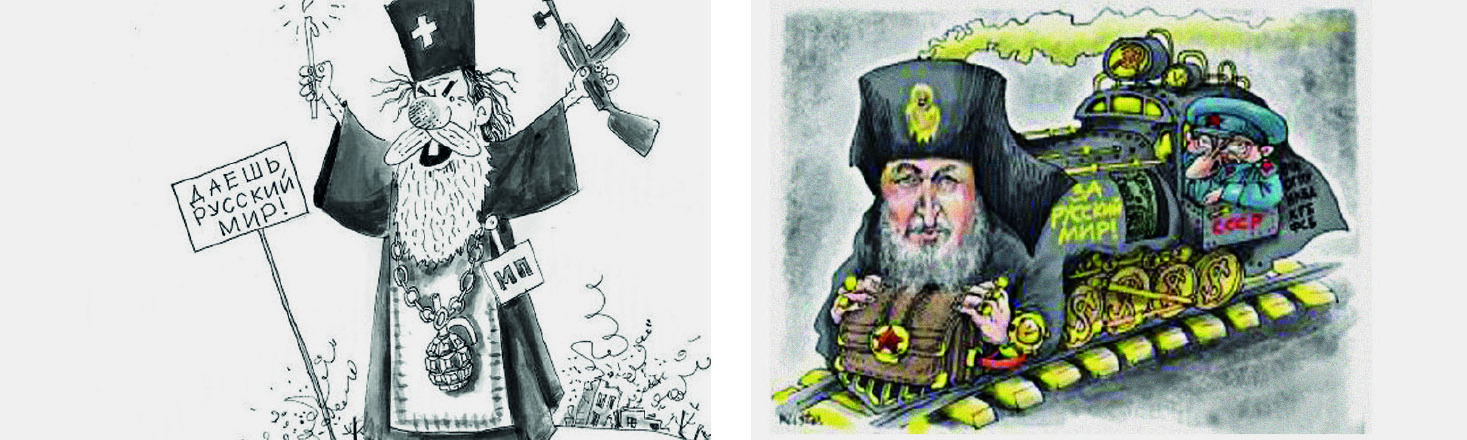

QUASI-RELIGION AS A BASIS FOR QUASI-IDEOLOGY: UKRAINE PUTS A CROSS ON THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

The Russian Orthodox Church, as one of the pillars of the “Russian world” and mouthpiece of the Kremlin, is also being deconstructed in the Ukrainian discourse. The caricatures below emphasize the connection between the Russian Church and “russkii mir”. Ill. 40 illustrates that priests of the Moscow Patriarchate support and bless the war, as is also evidenced by such attributes of war as a machine gun and a grenade instead of a cross. In this way, Volodymyr Solonko emphasizes that in fact there is nothing sacred in the ideology of the Moscow Church. Moreover, Patriarch Kirill is seen as a locomotive pulling the “Russian world” and Soviet past, including the KGB (lit. Committee for State Security) as well as the FSB (lit. Federal Security Service) (ill. 41).

Caricature by Volodymyr Solonko

Ill. 40. Let’s build “russkii mir” [96] Ill. 41. For “russkii mir”, USSR, KGB, FSB [97]

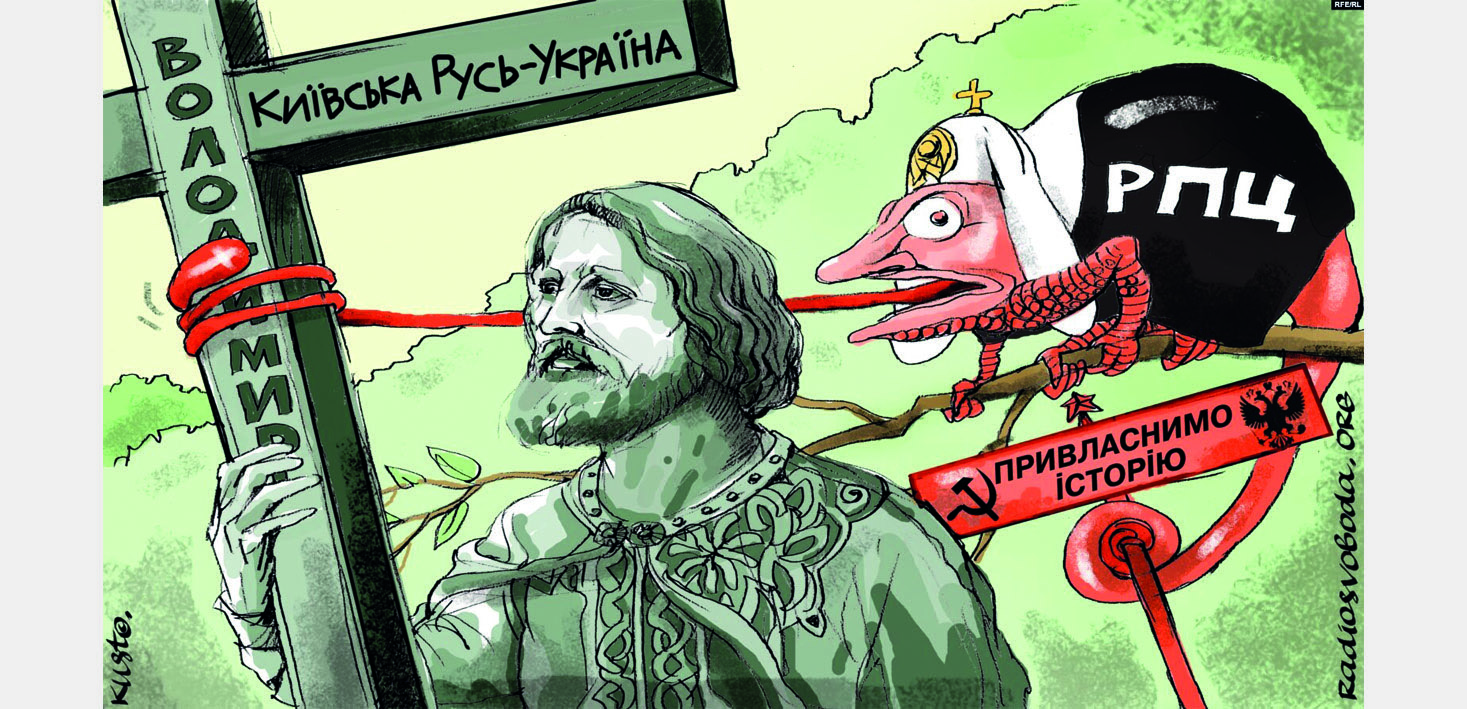

Particular attention is focused on the Figure of Patriarch Kirill as one of the main ideologists of the “Russian world”. In particular, his ambition to destroy and bury Ukraine (ill. 42) and his false statements about his desire for peace, as evidenced by a bloodied white dove (ill. 43), have been depicted. The tentacles of the octopus symbolize the aggressive attitude of Kirill and the Kremlin toward the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and the appetite to control it (ill. 44). Ill. 45 illustrates that the Russian Federation, as well as the Russian Orthodox Church, aims to appropriate the history of Kyivan Rus, proclaiming itself its successor. Snyder points out that “in his first address to the Russian parliament as president in 2012, Putin described his place in the Russian timescale as the fulfilment of an eternal cycle: as the return of an ancient lord of Kyiv, whom Russians call Vladimir. The politics of eternity requires points in the past to which the present can return, demonstrating the innocence of the country, the leader’s right to rule, and “the pointlessness of thinking about the future”.[98] Numerous monuments, fiction films, documentaries, and animated movies are intended to establish the view that Prince Volodymyr is a Russian hero, and Putin is continuing his work to unite the lands.[99]

Oleksandr Grekhov

Ill. 42.[100] Ill. 43.[101] Ill. 44.[102]

Political caricature by Oleksii Kustovskyi

Ill. 45.[103]

In autumn, the Security Service of Ukraine began searching for indicators of pro-Russian activities in the churches of the Moscow Patriarchate. According to law enforcement officers, these searches are carried out to “prevent the use of religious communities as a centre of the ‘Russian world’ and to protect people from provocations and terrorist acts”.[104]

For example, on the territory of St Cyril and Methodius Convent of Mukachevo Diocese of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (MP) in Zakarpattia, the Security Service of Ukraine found a large number of propaganda materials. Most of the literature is authored by Russian figures and published by Russian printers. The law enforcement officers discovered books of xenophobic content with offensive fiction about other nationalities and religions. In the pamphlets found, Ukraine’s right to independence is denied, and it is emphasized that Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus “cannot be divided”.[105] Moreover, since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, parishes of the Moscow Patriarchate have been joining the Orthodox Church of Ukraine to distance themselves from Russia and its false ideology.[106] Ukrainian popular culture, in particular memes and caricatures, reacts to all these processes in society and depicts the desire of Ukrainians to separate from this Kremlin-controlled church. Being a member of the Russian Orthodox Church is characterized as a bad habit, along with such habits as nail biting or nose picking (ill. 46). Patriarch Kirill is depicted as a mole that has been insidiously “digging holes” under the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and has finally been exposed. Moreover, in espionage jargon, a mole is a long-term spy (espionage agent), so this metaphor is not accidental since Kirill is a former KGB agent (ill. 48). One meme (ill. 47) is based on the characters of the well-known Turkish TV series “Roksolana”, where Sultan Suleiman supports the Ukrainians’ desire to expel the Moscow Patriarchate with the well-known slogan “Glory to Ukraine”.

Yulia Vasyuk Yulia Vasyuk

Ill. 46. Top: Disgusting habits that you should get rid of Ill. 47. Sulik, guess what, my (Ukrainians – L.P.) have finally

Left: Picking your nose decided to expel the Moscow Patriarchate.

Right: Biting your nails[107] Glory to Ukraine! [108]

Bottom: Going to the church of the Moscow

Patriarchate105

Political caricature by Oleksii Kustovskyi

Ill. 48.[109]

Therefore, in Ukraine the ideology of the “Russian world” is being deconstructed, in particular its main components: history, language, and religion. In memes, caricatures, and songs, authors refute and ridicule the imperialist myth about the “cradle of three fraternal peoples”, showing the true cruel face of the Russian world, exposing the true intentions of the Russian Orthodox Church and its role in spreading the Kremlin’s narratives, and supporting the desire of Ukrainians to distance themselves from this imperialist ideology.

CONCLUSION

Pop culture plays a crucial role in Ukrainian resistance against Russian aggression. The numerous memes, images, cartoons, caricatures, and pieces of graffiti that have appeared during the full-scale invasion help to maintain the spirit of the Ukrainian people. The visual components of these new artifacts are often based on elements of national culture, such as national colours, images of national heroes, such as Cossacks, traditional Ukrainian clothes (vyshyvankas) and so on. Audial components often refer to traditional Ukrainian songs, ballads, and folklore, at the same time intertwining them with modern interpretations. Textual elements involve a lot of humorous content, in particular black humour and political satire that mocks the enemies. Concerning language choice, local dialects are used to underline national and regional identity. Verbal aggression, which naturally occurs in wartime, is more presented in bottom-up texts and is softened in official discourses. Contemporary Ukrainian culture has influenced Western global trends, since on the global arena Ukrainians – politicians, soldiers, but also civilians – are perceived as superheroes. Famous world-known artists and Hollywood actors have visited Ukraine to perform in support of the Ukrainian people. This intertwining of global trends and the war context brings a special artistic perspective.

Deconstruction of “russki mir” ideology in pop culture involves several levels: historical myths about the unity of nations, the authenticity of the Ukrainian language, and the Ukrainian’s right to their own orthodox religion. In the times of the ongoing full-scale war, Ukrainians have created their own identity by distancing themselves from the Russian cultural and linguistic space, dissociating themselves from the Russian Orthodox Church, and refuting myths about the “triune nation” and “fraternal peoples”. The Russian language, as one of the pillars of the Russian world, is no longer playing a significant role in Ukraine as it is perceived as the language of the enemy and the occupier.

Represented in various genres, this deconstruction has formed both the self-image of Ukrainians as brave, kind, noble people, and the image of the enemy as cruel, stupid and fanatic. The combination of audial, visual and textual elements in the artefacts of deconstruction enables the creation of powerful messages that reach not only Ukrainian but also Western audiences.

Therefore, the article opens a discussion about the role of pop culture in times of war. This article aims to outline the main trends in pop culture during the full-scale Russo-Ukrainian war. There are several directions in which pop culture of resistance could be investigated further: focusing on a specific genre, topic, historic or contemporary public figure, or on repetitive patterns and themes; a comparison of pop culture from the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian war (2014) and current artefacts, or comparison with cultures of resistance in other countries.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

‘5 pics: Street Artist Seth on Putins War on Ukraine (in Paris)’, Street Art Utopia, February 2022, <https://streetartutopia.com/2022/02/27/street-artist-seth-on-putins-war-on-ukraine-in-paris/> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Amelika Ocean. Ne braty, a katy [Not brothers, but executioners], online video recording, YouTube, March 2022 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RwePhj8rPro> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Balthaser, B., ‘From Schlemiel to Super Hero. Volodymyr Zelensky and the Price of Western Inclusion’, Spectre Journal, March 2022 <https://spectrejournal.com/from-schlemiel-to-superhero/> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

‘Bandera, flešmob i rosijski ZMI. Jak video lvivskykh školjarok stvorylo trend ta obroslo fejkamy’, New Voice, October 2021 <https://nv.ua/ukr/ukraine/events/batko-nash-bandera-ukrajina-mati-yak-ukrajinskiy-tiktok-trend-oburiv-zmivideo-50190872.html> [accessed on 27 January 2023]

Berezhanskyi, I., ‘Be brave like Ukraine: svit zapolonyly bilbordy z reklamoju smilyvosti ukrajintsiv’, TSN, April 2022 <https://tsn.ua/ato/be-brave-like-ukraine-svitzapolonili-bilbordi-z-reklamoyu-smilivosti-ukrayinciv-2040436.html> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Bidenko, A., ‘Jak vrjatuvaty svit vid Rosiji’, Ukrajinska pravda, May 2022 <https://www.pravda.com.ua/columns/2022/05/27/7348914/> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Bilaniuk, Laada , ‘Purism and Pluralism: Language Use Trends in Popular Culture in Ukraine since Independence’, Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 35.1/4: Battle for Ukrainian. A Comparative Perspective (2017–2018), 293–309

Bondarenko, D., ‘Socmereži zapolonyly memy pro Stepanu Banderu, jakoho “ožyvyv” Kadyrov’, Sajt mista Ternopolia, March 2022 <https://www.0352.ua/news/3351885/socmerezizapolonili-memi-pro-stepana-banderu-akogo-oziviv-kadirov-foto-video-18> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Buckley, T., ‘Star Wars’ Actor Mark Hamill’s Campaign Sends 500 Drones to Ukraine’, Bloomberg, October 2022 <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-10-19/-star-wars-actor-mark-hamill-scampaign-sends-500-drones-to-ukraine> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Chotyn, R., ‘Ji, Ji, Ji… Ukrajinsʹke pidpillja literoju «Ji» boretʹsja z Rosijeju na okupovanych terytorijach’, Radio Svoboda, October 2022 <https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/ukrayina-rosiya-viyna-okupatsiya-mova-litera-yi/32083789.html> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Dmytruk, A., ‘Nikohda my ne budem brat’jami!’ (pesnja Anastasiji Dmytruk), online video recording, YouTube, April 2014, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jj1MTTArzPI> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Dmytruk, A., ‘Nikohda my ne budem brat’jami!’, online video recording, YouTube, March 2014 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qv97YeC563Y> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Dubovskyi, V., ‘Proščalʹnyj marš’, online video recording, YouTube, August 2014

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vzKp-Yjc7hQ> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Gault, M., ‘Shitposting Shiba Inu Accounts Chased a Russian Diplomat Offline’, Vice, July 2022, <https://www.vice.com/en/article/y3pd5y/shitposting-shiba-inu-accounts-chased-arussian-diplomat-offline> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Heil, J., ‘Ne sestry’, online video recording, YouTube, September 2022 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=paMlNnxMuGQ> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Hordijchuk, D., ‘“Ruskij vojennyj korablʹ … vsʹo…”: Ukrpošta anonsuvala prodaž novoji seriji marok’, Ukraijinska pravda, May 2022 <https://www.epravda.com.ua/news/2022/05/19/687212/> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Johnston, R., ‘DC Comics To Introduce New Ukrainian Superhero, Core’, BC, November 2022 <https://bleedingcool.com/comics/dc-comics-to-introduce-new-ukrainiansuperhero-core/> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Kalush Orchestra – Stefania – LIVE – Ukraine – Grandfinal – Eurovision 2022, online video recording, YouTube, May 2022 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F1fl60ypdLs&list=RDMMF1fl60ypdLs&start_radio=1> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Kelaidis, K., ‘The Russian Patriarch just gave his most dangerous speech yet – and almost no one in the West has noticed’, Religion Dispatches, April 2022 <https://religiondispatches.org/the-russian-patriarch-just-gave-his-most-dangerous-speech-yet-and-almostno-one-in-the-west-has-noticed/?fbclid=IwAR2cfewGhXlCSyBqAvM98ONB24DKhzNynaqOpnNsS9BAaAONVaQXmwveP0Y> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Knoblock, N. (ed.), Language of Conflict: Discourses of the Ukrainian crisis (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020)

Kress, G., and T. Van Leeuwen, Reading Images (London: Routledge, 2006)

Kulyk, V., ‘Die Sprache des Widerstands. Der Krieg und der Aufschwung des Ukrainischen’, Osteuropa, 6–8: Widerstand. Ukrainische Kultur in Zeiten des Krieges, (2022), 237–48

Kusse, H., Agression und Argumentation: mit Beispielen aus dem russisch-ukrainische Konflikt (Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag, 2019)

Lange, A., ‘The Beginning of Ukrman – a Fighter against the Evil and the Coronavirus’, Galactica Media, October 2020 <https://galacticamedia.com/index.php/gmd/article/view/118 [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Laruelle, M., The ‘Russian World’: Russia’s Soft Power and Geopolitical Imagination. (Washington: Center on Global Interests, 2015)

Masenko, L., ‘Ukrajina i Rosija. Knjaz’ Volodymyr i pochodžennja ukrajins’koji movy’, Radio Svoboda, November 2016 <https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/28111096.html [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Melezhyk, T., ‘Stefania: tekst, istorija stvorennia, sens pisni ta jiji vplyv na ukrajinsku kul’turu’, TSN, May 2022 <https://tsn.ua/ato/stefania-tekst-istoriyastvorennya-sens-pisni-ta-yiyi-vpliv-na-ukrayinsku-kulturu-2063092.html> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Moody, A., ‘Language Ideology in the Discourse of Popular Culture’, in: The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, ed. by C.A. Chapelle (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012)

‘Moskovsʹkyj patriarchat: skilʹky chramiv zalyšylosʹ na Chmelʹnyččyni’, Spiritual Front of Ukraine, November 2022 <https://df.news/2022/11/13/moskovskyj-patriarkhat-skilky-khramivzalyshylos-na-khmelnychchyni/> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Mukerji, Chandra, and Michael Schudson, ‘Popular culture’, Annual Review of Sociology (1986), 47–66

‘Mulfilm “Tri sestry”’, online video recording, YouTube, May 2022 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=crGk0X_oJjk> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Nikitiuk, L., and S. Giga, ‘Cej son, cej son’ [This dream, this dream], online video recording, YouTube, June 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x8DOfGW86sQ&list=RDx8DOfGW86sQ&start_radio=1> [accessed on 27 January 2023]

O’Halloran, Kay L., ‘Multimodal discourse analysis’, in K. Hyland and B. Paltridge (eds), The Continuum Companion to Discourse Analysis (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011), pp. 120–36

O’Toole, M., The Language of Displayed Art (London: Leicester University Press, 1994).

Orlova, V., ‘Na shodi ta pivdni Ukrajiny pokraščylos stavlennja do Stepana Bandery’, Unian, May 2022, <https://www.unian.ua/society/na-shodi-ukrajini-perevazhaye-pozitivne-stavlennyado-stepana-banderi-opituvannya-novini-ukrajini-11812350.html> [accessed on 27 January 2023]

‘Patriarkh Kirill nazval Donbass “perednej linijej oborony Russkogo mira”’, TASS, December 2022, https://tass.ru/obschestvo/16475189> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

‘Patriaršeje slovo po slučaju Dnja narodnogo edinstva’, Official website of the Moscow Patriarchate, November 2022, http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/5973837.html> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Pennycook, Alastair, ‘Nationalism, Identity and Popular Culture’, in Sociolinguistics and Language Education, ed. by Nancy H. Horberger and Sandra Lee McKay (Bristol–Buffalo–Toronto: Multilingual Matters, 2010), p. 65.

Pidkuimukha, L., ‘Myths and Myth-Making in Current Kremlin Ideology’, in A. Giannakopoulos (ed.), Politics of Memory and War. From Russia to the Middle East, ed. by Angelos Giannakopoulos, Series Research Papers 11 (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University – The S. Daniel Abraham Center for International and Regional Studies, 2022), pp. 38–53.

Pikulyna, K., ‘Kalush Orchestra – Stefania: povnyj tekst i sens chitovoji pisni’, Unian, May 2022, <https://www.unian.ua/lite/music/kalush-stefaniya-povniy-tekst-i-zmistpisni-11822220.html> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Plat, P., ‘How Marvel fans are turning Ukraine’s plight into dark “entertainment’’, The Telegraph, March 2022, https://streetartutopia.com/2022/02/27/street-artist-seth-on-putins-war-on-ukraine-in-paris/> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Polegkyi, O., and D. Bushuyev, ‘Russian foreign policy and the origins of the “Russian World”’, Forum for Ukrainian Studies, September 2022 <https://ukrainian-studies.ca/2022/09/06/russian-foreign-policy-and-the-origins-of-the-russian-world/#4> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Prasad, A., ‘DC predstavljatʹ novoho ukrajinsʹkoho superheroja v komiksach’, Forbes.ua, November 2022 <https://forbes.ua/news/dc-predstavlyat-pershogo-ukrainskogo-supergeroya-ukomiksakh-28112022-10092> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

‘Proroči slova Ševčenka na bilbordi u zvilnenij Balakliji’, online video recording, YouTube, October 2022 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HD8s2Xv7Cn0> [accessed on 27 January 2023]

Samosvat, I., ‘“Dobroho večora, my z Ukrajiny”. 8 brendiv, ščo stvorjujutʹ patriotyčni kolekciji j dopomahajutʹ ZSU’, Scho tam, April 2022, <https://shotam.info/dobroho-vechora-my-z-ukrainy-8-brendiv-shcho-stvoriuiutpatriotychni-kolektsii-y-dopomahaiut-zsu/> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Sarkar, M., and B. Low, ‘Multilingualism and popular culture’, in The Routledge handbook of multilingualism (Routledge, 2012), 417–32

‘SBU pereviryla monastyr UPC (MP) na Zakarpatti, de černyci zaklykaly do “probuždenyja matušky-Rusy”’, Telegram Channel of Security Service of Ukraine, December 2022 <https://t.me/SBUkr/6000> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

SBU provodytʹ bezpekovi zachody na ob’jektach UPC (MP) u dev’jaty oblastjach Ukrajiny’, Security Service of Ukraine, December 2022, <https://ssu.gov.ua/novyny/sbu-provodyt-bezpekovi-zakhody-na-obiektakh-upts-mpu-deviaty-oblastiakh-ukrainy> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Semkiv, R., ‘Contemporary war in Ukraine, and the birth of a new Ukrainian satire’, online video recording, YouTube, December 2022 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fbga8ZvxamE> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Semotiuk, O., ‘Russian-Ukrainian Military Conflict in American, German, and Ukrainian Political Cartoons: Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis’, Visnyk Lvivskoho Universytetu. Seija Zhurnalistyky, 45 (2019), 280–90

Semotiuk, O., ‘Russian-Ukrainian Military Conflict: Terminological and Discursive Dimension’, Visnyk Lvivskoho Universytetu. Seija Zhurnalistyky, 51(2022), 96–105

Shaw, A., ‘Banksy in Ukraine: seven new works appear in war-torn sites’, Art Newspaper, November 2022, <https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/11/14/banksy-in-ukraine-seven-new-works-appearin-war-torn-sites> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Shuster, S., ‘How Volodymyr Zelensky Defended Ukraine and United the World’, TIME, March 2022 <https://time.com/6154139/volodymyr-zelensky-ukraine-profile-russia/?utm_source=pocket-newtab> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Snyder, T., The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2018)

‘Stratehija nacional’noj bezopasnosti Rossijskoj Federacii’, Kremlin, July 2022, http://static.kremlin.ru/media/events/files/ru/QZw6hSk5z9gWq0plD1ZzmR5cER0g5tZC.pdf

Šumycka, H., L. Pidkujmucha, N. Kiss, ‘Mova jak “bajraktar”, mova jak kod: do juvileju sociolinhvistky’, Radio Svoboda, November 2022 <https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/larysa-masenko-ukrayinska-mova/32126052.html> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Tiškov, V., ‘Russkij mir: smysl i strategii’, Russkijmir.ru, December 2017 <https://m.rusmir.media/2007/12/01/strategia> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Trotta, J., ‘Pop Culture and Linguistics – Is That Like a Thing Now?’, in Valentin Werner (ed.), The Language of Pop Culture, ed. by id. Routledge Studies in Linguistics (Routledge: 2018), pp. 27–53

Ukaz Prezidenta Rossijskoj Federacii ot 05.09.2022 № 611 “Ob utverždenii Koncepcii gumanitarnoj politiki Rossijskoj Federacii za rubežom”’, Official Internet portal of legal information, <http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001202209050019> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

‘Ukrajinsʹkyj chlopčyk spivaje “Oj u luzi červona kalyna”’, online video recording, YouTube, March 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cIJiM1jKyOE> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Walfisz, J., ‘“The Wall” murals spread across Europe in cultural solidarity with Ukraine’, Euronews, November 2022, <https://www.euronews.com/culture/2022/11/11/the-wall-murals-spread-across-europe-incultural-solidarity-with-ukraine> [accessed on 19 January 2023]

Werner Valentin, ‘Linguistics and Pop Culture: Setting the Scene(s)’, in Valentin Werner (ed.), The Language of Pop Culture, ed. by id. Routledge Studies in Linguistics (Routledge: 2018)

Yuval-Davis, N., ‘Theorizing identity: beyond the “us” and “them” dichotomy’, Patterns of Prejudice, 44.3 (2010), 261–80

Yuval-Davis, Nira, ‘Theorizing identity: beyond the “us” and “them” dichotomy’, Patterns of Prejudice, 44.3 (2010), 261–80

[1] See for details Holger Kusse, Agression und Argumentation: mit Beispielen aus dem russisch-ukrainische Konflikt (Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag, 2019).

[2] For an overview of different approaches towards conflict analysis, see Natalia Knoblock (ed.), Language of conflict: discourses of the Ukrainian crisis (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020).

[3] Orest Semotiuk. ‘Russian-Ukrainian Military Conflict: Terminological and Discursive Dimension’, Visnyk Lvivskoho Universytetu. Seija Zhurnalistyky, 51(2022), 96–105.

[4] See for details Valentin Werner, ‘Linguistics and Pop Culture: Setting the Scene(s)’, in id. (ed.), The Language of Pop Culture, Routledge Studies in Linguistics (Routledge: 2018), pp. 3–26.; Joe Trotta, ‘Pop Culture and Linguistics – Is That Like a Thing Now?’, in Werner (ed.), The Language of Pop Culture, pp. 27–53.

[5] Andrew Moody, ‘Language Ideology in the Discourse of Popular Culture’, in: The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, ed. by C.A. Chapelle (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), p. 1 <https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0626>.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Alastair Pennycook, ‘Nationalism, Identity and Popular Culture’, in Sociolinguistics and Language Education, ed. by Nancy H. Horberger and Sandra Lee McKay (Bristol–Buffalo–Toronto: Multilingual Matters, 2010), p. 65.

[8] Mela Sarkar and Bronwen Low, Multilingualism and popular culture. The Routledge handbook of multilingualism (Routledge, 2012), p. 405.

[9] Pennycook, ‘Nationalism, Identity and Popular Culture’, p. 78.

[10] Werner, ‘Linguistics and Pop Culture’.

[11] Laada Bilaniuk, ‘Purism and Pluralism: Language Use Trends in Popular Culture in Ukraine since Independence’, Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 35.1/4: Battle for Ukrainian. A Comparative Perspective (2017–2018), 293–309.

[12] Chandra Mukerji and Michael Schudson, ‘Popular culture’, Annual Review of Sociology, (1986), 47–66 (p. 48).

[13] Kay L. O’Halloran, ‘Multimodal discourse analysis’, in K. Hyland and B. Paltridge (eds), The Continuum Companion to Discourse Analysis (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011), p. 121.

[14] Michael O’Toole, The Language of Displayed Art (London: Leicester University Press, 1994); Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen, Reading Images (London: Routledge, 2006).

[15] See for details Orest Semotiuk, ‘Russian-Ukrainian Military Conflict in American, German, and Ukrainian Political Cartoons: Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis’, Visnyk Lvivskoho Universytetu. Seija Zhurnalistyky 45 (2019), 280–90.

[16] Dana Hordijchuk, “Ruskij vojennyj korablʹ … vsʹo…”: Ukrpošta anonsuvala prodaž novoji seriji marok, Ukraijinska pravda, May 2022, https://www.epravda.com.ua/news/2022/05/19/687212/ [accessed on 19 January 2023].

[17] Rostyslav Semkiv, ‘Contemporary war in Ukraine, and the birth of a new Ukrainian satire’, online video recording, YouTube, December 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fbga8ZvxamE [accessed on 19 January 2023].

[18] Source: https://fakty.ua/399975-ne-bolshe-30-shtuk-v-odni-ruki-ukrainskaya-pochtovaya-marka-s-poslannym-russkim-korablem-stala-raritetom, 18 April 2022 [accessed on 27 January 2023].

[19] Source: https://www.epravda.com.ua/news/2022/05/19/687212/ [accessed on 27 January 2023].

[20] I. Berezhanskyi, ‘Be brave like Ukraine: svit zapolonyly bilbordy z reklamoju smilyvosti ukrajintsiv’ TSN, April 2022, https://tsn.ua/ato/be-brave-like-ukraine-svit-zapolonili-bilbordi-z-reklamoyu-smilivosti-ukrayinciv-2040436.html [accessed on 19 January 2023].

[21] Source: https://agroelita.info/zapustyly-telegram-kanal-ahrarnyy-desant-pro-vklad-ahrariiv-u-peremohu-ukraini-u-viyni/, 12 March 2022 [accessed on 27 January 2023].

[22] Source: https://life.liga.net/istoriyi/article/et o-byli-pomidory-ligalife-nashla-kievlyanku-sbivshuyu-vrajeskiy-dron-bankoy-konservatsii [accessed on 27 January 2023].

[23] I. Samosvat, ‘“Dobroho večora, my z Ukrajiny”. 8 brendiv, ščo stvorjujutʹ patriotyčni kolekciji j dopomahajutʹ ZSU’, Scho tam, April 2022, https://shotam.info/dobroho-vechora-my-z-ukrainy-8-brendiv-shcho-stvoriuiut-patriotychni-kolektsii-y-dopomahaiut-zsu/ [accessed on 19 January 2023].

[24] Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/CcfEW3eB8ps/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=79f4988c-c93c-4c18-bc74-70f80bb9dbe2 [accessed on 27 January 2023].

[25] Source: https://shotam.info/dobroho-vechora-my-z-ukrainy-8-brendiv-shcho-stvoriuiut-patriotychni-kolektsii-y-dopomahaiut-zsu/ [accessed on 27 January 2023].

[26] ‘Ukrajinsʹkyj chlopčyk spivaje “Oj u luzi červona kalyna”’, online video recording, YouTube, March 2022,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cIJiM1jKyOE [accessed on 19 January 2023].

[27] ‘Kalush Orchestra – Stefania – LIVE – Ukraine – Grandfinal – Eurovision 2022’, online video recording, YouTube, May 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F1fl60ypdLs&list=RDMMF1fl60ypdLs&start_radio=1 [accessed on 19 January 2023].

[28] Source: https://nv.ua/ukr/lifestyle/kalush-orchestra-peremogli-na-yevrobachenni-reakciya-socmerezh-50242252.html [accessed on 19 January 2023].

[29] Ibid.

[30] Semkiv, ‘Contemporary war’.

[31] ‘Proroči slova Ševčenka na bilbordi u zvilnenij Balakliji’, online video recording, YouTube, October 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HD8s2Xv7Cn0 [accessed on 27 January 2023].

[32] Source: https://anekdot.kozaku.in.ua/karukatu/viyskovuh/6503-arta-orkiv-zustrichaie.html [accessed on 27 January 2023].

[33] Source: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/26669822784264682/ [accessed on 27 January 2023].

[34] D. Bondarenko, ‘Socmereži zapolonyly memy pro Stepanu Banderu, jakoho “ožyvyv” Kadyrov’, Sajt mista Ternopolia, March 2022, https://www.0352.ua/news/3351885/socmerezi-zapolonili-memi-pro-stepana-banderu-akogo-oziviv-kadirov-foto-video-18 [accessed on 19 January 2023].